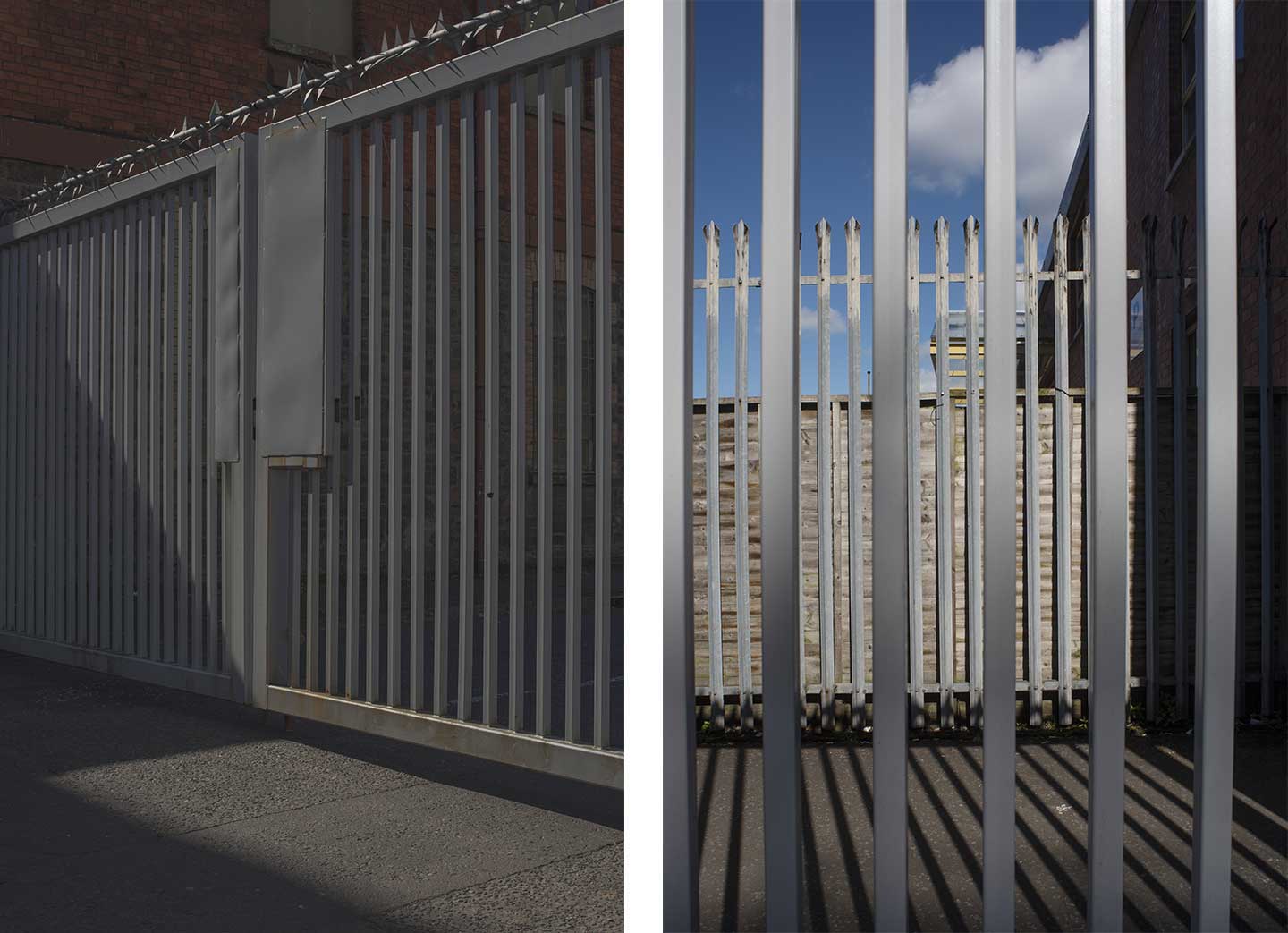

Detail of the “peace lines” gates that close Belfast’s North Howard street. All photos by Johannes Frandsen and Mattias Lundblad.

On April 18, during a night of rioting in the Northern Ireland city of Londonderry, the journalist Lyra McKee was shot and killed by the dissident group New IRA. The murder of the 29-year-old journalist, shocking in its own right, also brought back dark memories of a brutal conflict that Northern Ireland has tried to forget since the peace agreement in 1998.

“The Troubles,” as the three decades of violence is known, began in the late 1960s and claimed over 3,500 lives. On its surface the conflict appeared to stem from a religious divide between Catholics (who largely leaned Republican, wanting the British territory of Northern Ireland to become part of the Republic of Ireland) and Protestants (who largely leaned Loyalist, wanting Northern Ireland to remain part of the UK). The 1998 Good Friday agreement brought an official end to the conflict and, also opened up the border between the territories—a border that had been the site of checkpoints, harassment, and murder.

Now that the UK is getting ready to leave the EU, no one knows what will become of the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic, the only land border between the UK and the EU, and the people of Northern Ireland are growing increasingly uneasy as negotiations drag on. The so-called “backstop agreement” that the EU and the government at Westminster agreed on last year has also been a key sticking point in the UK, and one main reason that Theresa May’s withdrawal deals have not passed through Parliament.

The 310-mile-long border between Ireland and Northern Ireland divides rivers and fields, and even, occasionally, cuts through the odd house. No one wants a hard border again, and any kind of border surveillance would likely spark violence. Despite occasional sparks of violence, the days of the Troubles are behind, and the watchtowers and turrets that once lined the border have vanished. While the border no longer really exists for the people who live along it, it is different in the Northern Ireland city of Belfast. All over the city, neighborhoods are separated by walls and fences.

A view from the predominantly Catholic west Belfast, with walls cutting neighborhoods off from each other.

During the height of the Troubles, the Northern Ireland Department of Justice took over land to create physical obstacles in an effort to quell the violence, Department of Justice official John Chittick told us. What was presented as a quick, temporary solution soon became part of the fabric of Belfast. To this day, the segregation between Catholic and Protestant is manifested in concrete, brick, corrugated metal, and chain-link fencing. The walls, euphemistically known as “peace lines,” contribute to the harshness of the city. The opening and closing of heavy gates keep the rhythm of the day, and the interface areas, neighborhoods cut through by these walls, are where much of the violence occurred.

In 2013, plans were made to rid the city of peace lines within a decade. But the residents hesitated. Where the walls now stood, there had already been psychological barriers for years. Everyone knew all too well where they belonged and where they did not. That is how Belfast evolved since industrialization: People from different parts of the country came for work and built their neighborhoods with people with similar background. The city was segregated by religion and national identity. With physical barriers between neighbors, the social separation only increased and still remains today.

The Springfield Road neighborhood in west Belfast.

A Protestant primary school built right up to a wall, as seen from Bryson street in the Catholic Short Strand neighborhood.

A metal barrier divides Manor Street and continues along the line of Roe Street to Clifton Park Avenue.

Andersonstown, on the western outskirts of Belfast, was a major center of civil unrest during the conflict. When Catholics fled violence and intimidation of the inner-city areas in the 1970s, many relocated here. The communities separated into distinct areas—Protestant Suffolk and Catholic Lenadoon. John Hoey manages Stewartstown Road Regeneration Project, a commercial building on the interface between Suffolk and Lenadoon. The building has one entrance from Suffolk and one from Lenadoon, and is co-owned by the two communities. The project had substantial support from the government, but caused a fair deal of trepidation from the communities when it was built in 2001, says Hoey. As revenue from the tenants started coming in and was divided between the communities, though, the project was accepted, and it’s now a successful effort of cross-community collaboration. That does not mean the barriers, either social or physical, are gone.

Stewartstown Road Regeneration Project, a commercial building, co-owned by Protestants and Catholics and one of the most successful interface projects of its kind.

“It would be impossible for a Nationalist Republican to live in Suffolk. They wouldn’t feel comfortable, and they probably wouldn’t be allowed to rent a house there. Similarly, a Protestant person would not rent a house in Lenadoon. People are still quite set on the territorial notion,” said Hoey.

He does not expect the government’s plan to dismantle the walls to be on schedule, nor does he see much interest for it in the communities. Although most of the violence has ceased, there are enough incidents to keep the tension and the need for walls on people’s mind.

“I haven’t met anybody in the area who actually wants to take the walls down,” Hoey said. “I lived six years at an interface, and I know it’s very frightening. These walls and barriers do give a sense of security. That is not to be dismissed.”

Short Strand, a small Catholic enclave in Eastern Belfast, is completely surrounded by walls separating it from the Protestant areas. The houses are built right up to the walls, and the residents can sit in their yard staring at a 25-foot-high wall while drinking afternoon tea.

Frankie Quinn, a local photographer who has devoted much of his work to the walls, showed us around in his neighborhood. He was born here 53 years ago, but his childhood home has been replaced by a high brick wall and a net fence that got its latest extension when unrest broke out in 2002.

The walls dividing Lower Oldpark and Cliftonville.

Left: The most well-known wall, separating Falls and Shankill, at Bombay Street. Right: The gates at Townsend Street.

The famous 40-foot-high wall separating Falls and Shankill Roads for half a mile, seen from North Howard Street. Today it is a popular spot for tourists.

Among the most notorious “interface areas” in North Belfast is that between the lower Antrim Road and the lower Shore Road, which was such a flashpoint that in 1994 a fence was added to Alexandra Park, dividing the park between the two communities. The fence remains in place, although a gate was added in 2011 permitting limited access from one side to the other. It is the only park in western Europe divided in this way.

Walking around, it’s clear that everyone knows everyone in Short Strand. A stranger stands out. The walls have created a strong community and it is impossible to find an empty house in Short Strand. Mr. Quinn, who has lived in this area his whole life, has watched the streets burn, seen friends getting killed, and watched the walls going up during the Troubles.

“I often want to leave this place, these walls are so depressing,” Quinn told us. “At the same time my connection to this place is so strong. I couldn’t live anywhere else but I am happy my kids moved.”

On our walk through Short Strand, we passed a group of children playing on a street corner. We asked him if he thinks the walls will disappear, but he just shook his head. “I will not see it happen, but maybe they will.”

Mattias LundbladMattias Lundblad is a Swedish freelance photographer and writer based in New London, Connecticut and Stockholm, Sweden. He reports from the US for European media, and vice versa.

Johannes FrandsenJohannes Frandsen is a photographer, artist, and publisher from Sweden currently based in Stockholm.