When US soldiers venture abroad, women’s bodies can become the occupied territories.

Akemi Johnson

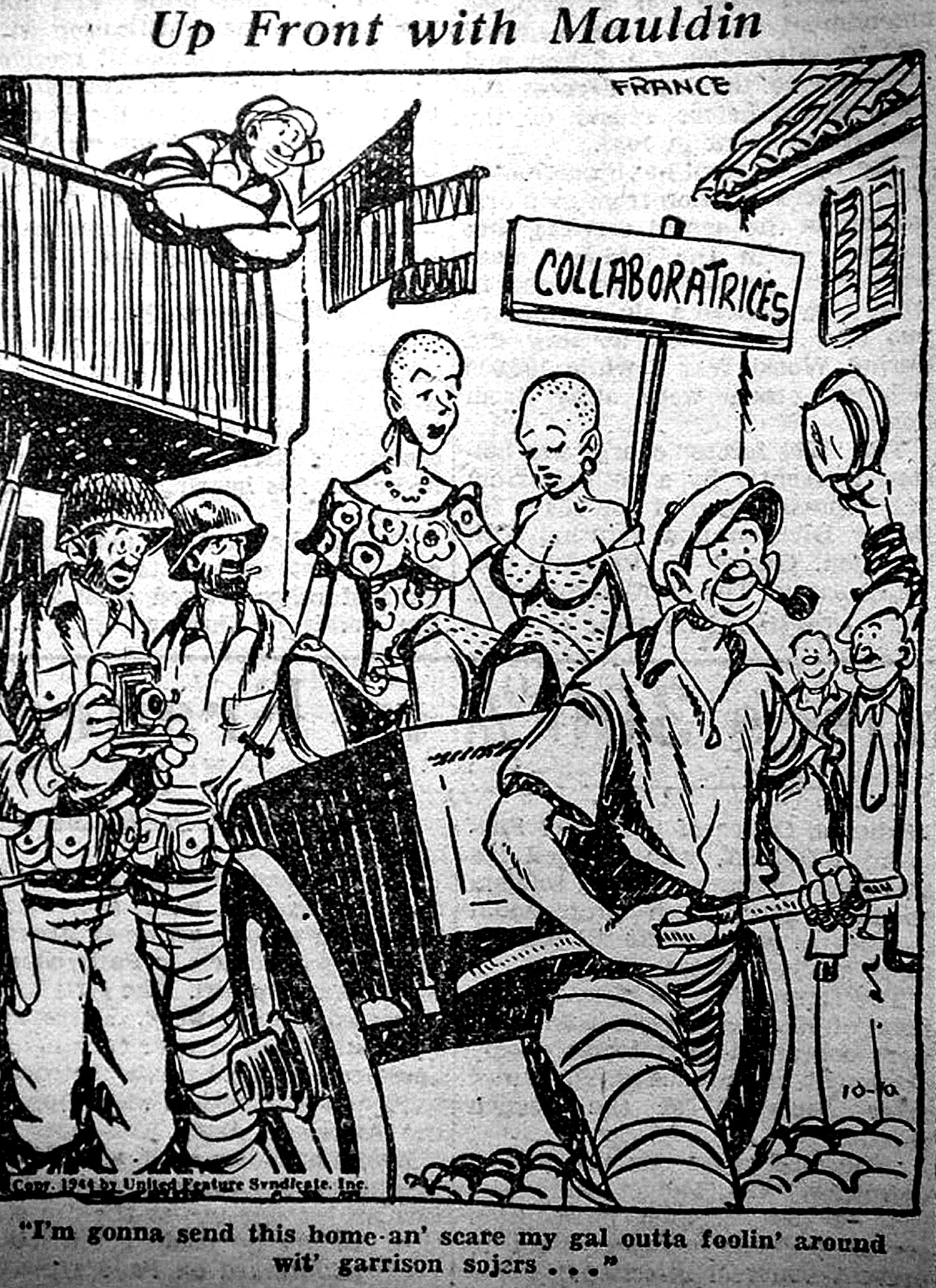

A cartoon by Bill Mauldin from the October 24, 1944, issue of Stars and Stripes

It was 4 am, and I was in a McDonald’s in Naha, the capital city of Okinawa, Japan’s southernmost prefecture. Down the street—International Street—was the nightclub that supplied the patrons at this hour: mostly US servicemen, young and bleary-eyed.

“It’s like the American embassy in here,” one man remarked, looking around.

My friend and I had come from the club too, but we were Asian-American women with no connection to the numerous US military bases that crowd the island. Over Quarter Pounders, we struck up a conversation with a serviceman. Justin, from Florida, was a Marine who had been stationed in Okinawa for the past ten months. He chatted with us amiably until the topic turned to the local dating scene. Then his expression went dark. He crushed a napkin in his fist and threw it onto his food tray.

“Fuck Saicolo,” he said, naming the establishment from which we’d all come. “I want to drop a bomb on that club.”

What Soldiers Do: Sex and the American GI in World War II France, by historian Mary Louise Roberts, suggests that this Marine’s comment is not insignificant. Roberts draws upon extensive sources, including diaries, police reports and court-martial transcripts, to examine the presence of American forces in France from 1944 to 1946. She contends that the sexual conduct of US servicemen in war should be moved from a historical footnote to “the center of the story.” Loaded with symbolism, sexual behavior in this context plays an important role in shaping the political and diplomatic negotiations of power between countries.

This rings true to someone who, for the past few years, has been researching and writing about the relationships between US servicemen and local women in Okinawa. The situation there shares notable similarities with the historical one that Roberts describes. The American military presence in both places began with bloody World War II conflicts: D-Day and the Normandy campaign in France, the Battle of Okinawa in Japan. Although France was an ally that the United States helped to liberate from German control, Roberts illustrates that the initial exhilaration and gratitude of French citizens quickly became complicated by the humiliation of defeat, anger and sadness over the devastation of their countryside, as well as uncertainty regarding France’s place in the world. America’s international power was on the rise, while France’s had declined. Exactly who would run France’s postwar government—autonomous French leaders or the Allied military—was unclear. This, along with the disruptive and frequently violent presence of American troops in French towns, led many Normans to see the United States as a second occupier. “Le Havre was literally invaded,” one Norman resident recalled. “You could not stick your nose out the door without seeing a Jeep or a Dodge drive by, or hundreds of soldiers walking around.” Many Okinawans feel a similar indignation in a prefecture that, despite its tiny landmass, hosts more than half of the 50,000 American troops stationed in Japan.

During the year I spent on the main island of Okinawa, from 2008 to 2009, I catalogued comments and interactions like the encounter in McDonald’s with a growing sense that they were more than just idle chatter. Justin, as he went on to explain, wanted to bomb that nightclub because he believed the Okinawan women there only wanted to date black men—and Justin was white. He wasn’t the only one with this view of island dating dynamics. Kokujo, local slang for women who prefer black men, were widely thought to be the largest subset of amejo, women who like Americans. They seemed to outnumber hakujo, women who favor white men, and spajo, women who prefer Latinos.

The number of women in Okinawa who identified based on their racial dating preferences surprised me, but it isn’t a new phenomenon. During World War II, Roberts writes, the US military was segregated, and the women in 1940s France who dated or serviced GIs often “specialized” in Americans, sometimes those of a specific race. After US forces entered France, military officials promptly segregated the brothels by rank and race. The military is no longer segregated, but soldiers tend to socialize as if it were. In Okinawa, black enlisted men frequented Saicolo, a cavernous, glitzy hip-hop club in downtown Naha; Latino enlisted men hung out at Salsatina, a cozy salsa dance club strung with Latin-American flags; and white officers took their recreation at Eclipse, a breezy, open-air bar on the water in Chatan. (If there were night spots whose primary clientele were servicewomen or officers of color, I never heard of them.) Local women are savvy to these distinctions and make choices about racial preferences as well as military status when deciding which bars to frequent. Justin didn’t need to annihilate Saicolo; he needed to hang out at a different club.

* * *

But Justin’s comment is rooted in the violent legacy of race and sex in the US military. In the most unsettling and final part of What Soldiers Do—following a section on romance and another on prostitution—Roberts examines rape. To horrifying effect, she describes how, in 1944 Normandy, American military authorities and French civilians employed a lethal racism toward black soldiers during a summerlong spate of rape accusations. In 1944 and 1945, twenty-five of the twenty-nine men hanged for rape in the European theater of operations were black. While censoring these figures for the American public, military officials cited them internally as proof that black men were morally depraved, sexually aggressive animals.

Roberts argues that a deadly combination of factors—pervasive stereotypes of black men, the segregation of soldiers, the legacy of Jim Crow lynching, the need for scapegoating—resulted in these racialized hangings. The alleged sexual crimes mostly occurred at night, in unlit rural areas, and amid a general atmosphere of miscommunication, wartime ruin and fear. Accusers often admitted to failing to get a good look at their assailants, but they were nevertheless confident that the men were black. Roberts cites one case in which the accuser—despite her weak eyesight and the darkness—was convinced that her rapists had been black because of their “speech, large lips and shiny skins.” American investigators often accepted such claims without question.

Once arrested, the defendants—who were not guaranteed legal counsel in US military courts—were often convicted with chilling speed. In one case, two African-American soldiers were charged, put on trial and sentenced to death within a week of the alleged rape. A white soldier would be afforded a more methodical trial, albeit one where bias worked in the opposite direction. The defense would take its time to question, and ideally discredit, witnesses and the accuser. French civilians were not without blame in this injustice. Roberts writes that, aware of the severity of an accusation, French prostitutes “were known to threaten black soldiers with charges of rape in order to extort higher fees for services.” Other women may have accused black men of rape out of fear of exposing interracial relationships, or out of fear of black men themselves. In a nation that had once colonized black subjects, the American men of different races who now patrolled its cities and towns became targets for deep-seated anxiety over France’s waning international power.

As for the US military, Roberts writes, it acted so swiftly and lethally in these rape cases because of the considerable damage that sexual violence caused to US-French relations. A rape undid the American military’s carefully crafted myth of the GI as manly hero, come to rescue the damsel in distress, France herself. Rape recast the GI as brutal invader, savagely taking his spoils of war. Scapegoating black soldiers and playing on French racism enabled the military to separate that damaging narrative from the larger one of the (white) GI hero that helped establish US control in a broken France.

The political and diplomatic costs of rape are vividly evident in Okinawa as well. Arguably the most explosive rape case in that arena has been the 1995 gang rape of a 12-year-old. A local schoolgirl, walking home one night in her neighborhood outside a US Marine Corps base, was abducted by three servicemen. The men threw her in the back seat of a rental car, bound and beat her, and drove her to a secluded spot, where they raped and left her. Sustaining injuries that would require two weeks of hospital treatment, the girl dragged herself to a nearby house for help and later provided police with descriptions of the men and the vehicle, leading to their arrest.

News of the story set off what scholar Chalmers Johnson later called “the greatest crisis in Japanese-American relations” in decades. Locally, Okinawans rallied against the rape, leading to the largest demonstration in the prefecture’s history (a record that remained unbroken until 2007, when citizens protested the government’s attempt to excise from textbooks the military’s role in the mass suicides that were urged upon Okinawans—and assisted by Japanese soldiers—during the fateful American invasion of 1945). In response to the 1995 uproar, Japanese and US politicians were forced to re-examine the “status of forces” agreement, part of the US-Japan Security Treaty, and renewed talks about relocating Marine Corps Air Station Futenma to a less populated area of the island.

Rape cases involving American servicemen snap people awake in a way that a helicopter crash or a barroom brawl or a threatened coral reef do not. Knowing this, activists in Okinawa have reduced the islanders’ grievances against the American military presence to just four words. The crimes and hazards associated with US service members there include traffic and training accidents, burglaries, assaults and murders, but printed on buttons and stickers is the simple slogan “NO Rape, NO Base.” The elimination of the latter would mean the eradication of the former.

This simplification discounts, among other complexities, the rapes committed by Okinawan and Japanese men as well as Japan’s dubious track record in aiding victims and prosecuting rape. But the slogan is effective because it is an allegory: the issue here is not sexual violence but sovereignty. Roberts illustrates this tendency to view war as a battle for control over female bodies. During World War II, victors tacked women onto the list of commodities won: “Just a few weeks ago,” an American army officer in Normandy wrote to his wife, “the Germans were using these roads, buildings, fields, chairs, tables, toilets, women, and now we are.” Meanwhile, for the vanquished, nothing signaled defeat more than sexual violence. “The worst humiliation for a soldier,” a character in a 1946 French novel declares, “is to abandon your country’s women to the whims of the conquerors.”

A rape by a soldier of a local woman is a visceral reminder of state subjugation: the presence of foreign men who, in France during the war, were there to liberate an occupied country and, in present-day Okinawa, still dominate the landscape due to a decades-old defeat and the uneven distribution of postwar burdens within the country. Even without finessing by the media or activists, a rape can come to stand for the whole transnational, political, historical situation, and it hits people in the gut, the way only a good metaphor can. In the 1995 case, the innocent girl became Okinawa, kidnapped, beaten and ravaged by a thuggish United States. Tokyo was the offsite pimp that enabled the abuse, having let the brute in.

* * *

Counter to the rape narrative are consensual sexual relationships between foreign soldiers and local women. For the home population, these relationships challenge cries for sovereignty by suggesting that women, and thereby the country, are submitting willingly to outside control. In liberated France, as Roberts describes, French women accused of having sexual relations with the German occupiers were publicly punished by French men. Members of the French Forces of the Interior (FFI)—Resistance fighters—brutalized women with what was known as the tonte ritual. After liberation, they seized alleged female “collaborators” and, in public spaces, stripped them, beat them and shaved their heads. Then they paraded the humiliated women through the streets, flaunting the repossession of territory that had been temporarily lost.

“What do you give a shit if I have declared my ass an open city?” Roberts quotes one French woman, about to be subjected to the tonte ritual. The historian imagines that the FFI member holding the shears “might have answered that, in fact, he cared a great deal. In his mind an open city and an open set of legs amounted to the same thing.” To French men, relationships between French women and US soldiers were potentially as menacing—“they threaten to cut the girls’ hair if they go out with Yanks,” one GI said—but to the US military, these relationships were primarily an opportunity for good PR.

In What Soldiers Do, Roberts illustrates how the military worked to present its mission in France as a joyful heterosexual romance, with America as the strapping male partner. These sexualized domestic terms, which played upon American fantasies of an erotic, hedonistic France—a land overflowing with wine and wanton women—were useful because they indicated international unity, naturalized America’s dominance and motivated weary troops.

The US military created this myth in large part through photojournalism, just then becoming a highly successful tool of propaganda that signaled authenticity but permitted manipulation. Photographs in Life magazine and Stars and Stripes, the military newspaper, showed the liberating GIs showered with kisses from ecstatically grateful French women. A photograph published in Stars and Stripes in September 1944 below the headline “Here’s What We’re Fighting For” depicts attractive French women crowded together, waving and elated. Roberts exposes the falseness of this image, which is actually a “clumsily pasted together” composite of photographs and drawings: “Stars and Stripes was clearly determined to create a happy female crowd, even if one did not exist.”

Stars and Stripes still uses stories of romance to quell larger anxieties about the military’s presence abroad. In Okinawa, I attended a baby shower for a local woman whose husband had been killed recently in Iraq. At 25, Hotaru Nakama Ferschke was fresh-faced and striking, with black hair and faint glitter around her large eyes. Before coming to the party, I had learned about her and her late husband, Michael Ferschke Jr., by reading Stars and Stripes. According to the paper, Hotaru had met her husband-to-be—a 21-year-old white Marine sergeant from Tennessee—at a party on Camp Schwab the previous year. When he asked her out, she replied no; with their cultural differences, she thought it would never work. But he persisted. “We discussed the different environments and cultures we grew up with and the difficulties we may face,” the paper quoted Hotaru as saying. “After a good talk, we both were convinced that we would be able to overcome any differences.”

A few months later, the relationship was serious: Hotaru spent Christmas with Michael in his hometown, a rural environment Hotaru “instantly liked” because it called to mind her own hometown in Okinawa. “I knew that I would fit in the town. And more than anything else, his family and relatives all accepted me so warmly.” Back in Okinawa, Michael decided to extend his re-enlistment another four years. His mother told the newspaper he’d said “he had not done his job yet. He said he was a team leader and he had to go with his men.” He knew that, by extending, he would be deployed to Iraq.

A month after he’d left, Hotaru realized she was pregnant. Michael pronounced the baby a miracle and the couple quickly arranged to marry by proxy. In July 2008, the couple wed. In August, Michael was killed in a firefight while clearing abandoned houses in the desert north of Baghdad.

At the baby shower, Hotaru stayed mostly quiet, one hand on her belly, her expression at once knowing and uneasy. Stars and Stripes had reported that she planned to move with the baby to Tennessee to live with her late husband’s parents. “I realized that it was best to raise him in the environment where his father grew up, so that he would feel his father’s presence and be proud of him,” the paper quoted her. When a guest at the shower asked about the move, Hotaru admitted that she was terrified. She was scared to live with near-strangers. She was scared she’d miss Japanese food. She was scared about the language barrier; she didn’t speak much English. Stars and Stripes hadn’t mentioned these fears, which echoed her initial concerns about navigating a cross-cultural relationship.

As Roberts points out, Stars and Stripes emerged as a propaganda vehicle during World War II. Michael and Hotaru’s story, like the American soldiers receiving appreciative kisses from French women, makes good military publicity: his passionate patriotism and ultimate sacrifice, her allayed worries, their international love story, the swelling embrace of the military community. “I have received tremendous support from the Marine Corps,” Hotaru was quoted in Stars and Stripes. Through her story, the paper hints at popular Okinawan concerns about the American presence—that the co-existence of local people and the US military is irreconcilable—and shuts them down. The soldier, standing in for his nation, kindly but firmly asserts that this is just another battle to be won. And America is proved right—a loving union results, with Okinawa a happy and devoted subordinate to a paternal if mostly moribund United States.

“The history of war,” Roberts writes, “cannot be separated from the history of the body.” Beyond combat, the bodies involved—the ones that physically connect, flesh upon flesh—are usually those of male soldiers, arrived from a foreign land to liberate, destroy or occupy, and those of female civilians, attracted or yanked into the military world. The interactions between them are intimate yet iconic, private yet political. A rape by an American soldier threatens to expose harsh realities about American hegemony; another GI’s part in an international romance suggests an entire country’s willing deference to benevolent US control. Harnessed for propaganda and protest, tangled in injustices like institutional lynching, these sexual relationships are essential to understanding war and its aftermath.

In Normandy, interactions between US soldiers and French civilians, which Roberts so meticulously and rivetingly details in What Soldiers Do, began on D-Day in 1944 and ended when the last troops departed a few years later. In Okinawa, US military-civilian relations began with the Battle of Okinawa in 1945 and persist to this day, playing out in the early morning hours in nightclubs and fast-food joints across the island.

Akemi JohnsonAkemi Johnson is a writer living in San Francisco. She is completing a creative nonfiction book about sex, race and war in Okinawa, Japan.