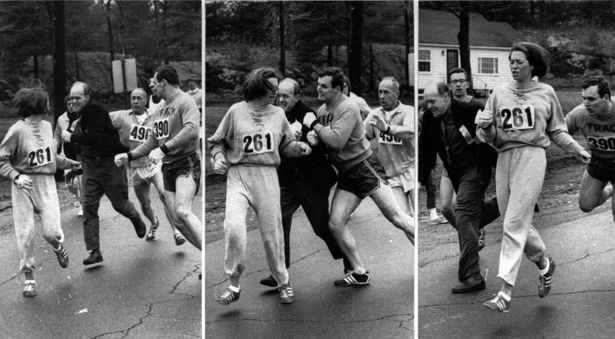

Kathrine Switzer found herself about to be thrown out of the normally all-male Boston Marathon when a companion threw a block that tossed a race official out of the running instead, April 19, 1967. (AP Photo)

“If you are losing faith in human nature, go out and watch a marathon.” – Kathrine Switzer

The dead. The injured. The anguish. All the result of bombs that were set to explode at the finish line just over four hours after the start of the Boston Marathon. Right now the sane among us will suggest caution. We’ll suggest restraint. We’ll suggest the giving of blood. There will be time to mourn. We will mourn the dead and injured. I also mourn the Boston Marathon and how it’s now been brutally disfigured.

The Boston Marathon matters in a way other sporting events simply do not. It started in 1897, inspired by the first modern marathon, which took place at the inaugural 1896 Olympics. It attracts 500,000 spectators and over 20,000 participants from ninety-six countries. Every year, on the big day, the Red Sox play a game that starts at the wacky hour of 11:05am so people leaving the game can empty onto Kenmore Square and cheer on the finishers. It’s not about celebrating stars but the ability to test your body against the 26.2 mile course, which covers eight separate Massachusetts towns and the infamous “Heartbreak Hill” in Newton. It’s as much New England in spring as the changing of the leaves in fall. It’s open and communitarian and utterly unique. And today it was altered forever. I spoke to my friend Jim Bullington who has ran in four Boston Marathons. He said,

For me and to any serious marathoner the Boston Marathon will always be the runner’s Holy Grail. Runners train and train and train for this race. If you qualify for the marathon you get the honor of running through all the beautiful outlying towns, you get to temporarily lose your hearing as you run by what seems to be thousands of deafening screaming women at Wellesley, you climb Heartbreak Hill, you run by all the college parties, you pass the CITGO sign and know you have one mile left, and finally when you make the final turn, you sprint by thousands of cheering people towards the finish line. Nothing is like it. Nothing. I just can’t imagine this. What is the most joyous occasion has turned into a tragedy of epic proportions.

Like a scar across someone’s face, the bombing will now be a part of the Boston Marathon, but also like a scar, we have to remember it’s only a part. If this bombing will always be a part of the Boston Marathon, then so is Kathrine Switzer. I want to tell the story of Kathrine Switzer because it’s about remembering the Boston Marathon as something more than the scene of a national tragedy.

Through 1966, women weren’t allowed to run the grueling 26-mile race. But in 1967, a woman by the name of Kathrine Switzer registered as K.V. Switzer and, dressed in loose fitting sweats, took to the course. Five miles into the race, one of the marathon directors actually jumped off a truck to forcibly remove Switzer from the course, yelling: “Get the hell out of my race!” But the men running with her fought him off. For them, Kathrine Switzer had every right to be there. For them, the Boston Marathon wasnʼt about exclusion or proving male supremacy—pitting boys against girls. It was about people running a race. Somehow Kathrine Switzer kept her pace as this mayhem occurred all around her. As she said, “I could feel my anger dissipating as the miles went by—you can’t run and stay mad!”

When the pictures from the marathon were transmitted across the globe, the world saw two opposing models of masculinity: the violence and paranoia of the marathon director vs. the strength and solidarity of the other male runners. And at the center of it all, the resolute focus of Kathrine Switzer. In that moment, sports bridged the gender divide and gave the world a glimpse into what was possible. Today, Kathrine Switzer says, “When I go to the Boston Marathon now, I have wet shoulders—women fall into my arms crying. They’re weeping for joy because running has changed their lives. They feel they can do anything.”

In 1967, the Boston Marathon gave us all a glimpse of the possible. Today we saw not of the world we’d aspire to live in, but the one we actually inhabit. Instead of the triumph of the individual amidst the powerful throngs and inspiration of the collective, we have tragedy, disarray, panic, and fear. Like a scar, it now marks us: the loss of security among the mass. But like a scar, we may need to wear it proudly. We will run next year because the alternative is too awful to contemplate.