California Governor Gavin Newsom and former governor Arnold Schwarzenegger arrive at a news conference in Ladera Heights.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)Not too long ago, California was a byword for budgetary chaos and dysfunction. Its deficits were routinely astronomical, its ability to adequately tax its population to fund its ambitious social programs hamstrung by tax-limiting laws such as Proposition 13. Year after year, its budget was submitted late, with the governor and legislators wrangling over its impossible math.

In February 2009, at the depth of the global financial crisis, California lawmakers struggled with how to close a $41 billion deficit, ultimately adopting a series of stark cuts as well as accounting gimmicks that fooled no one about the depth of the Golden State’s financial mess. In July of that year, the credit rating agency Fitch lowered California’s general bond obligation rating to BBB, putting it on a par with near-bankrupt countries such as Greece.

It’s taken a lot of hard work, under Governors Schwarzenegger, Brown, and Newsom, to right this budgetary ship. A combination of a more realistic willingness to raise taxes to fund obligations, combined with Governor Brown’s laser focus on building up a huge rainy day fund during years in which the state was riding high—across his two terms, the state went from a $27 billion deficit to having nearly $14 billion in the rainy day fund—has transformed the state’s finances. California went, in the space of just a few years, from a budgetary laughingstock to a state that has managed for the better part of a decade to offset the cost of its growing social safety net programs with a relatively progressive tax system that by and large generates sufficient funds to cover its obligations. In 2022, with the state flush with pandemic-era federal funds and a huge bump in tax revenues as wealthy residents saw their net worth hugely increase, Newsom signed a $307 billion budget for the upcoming year—taking on impressive new healthcare, environmental, and other commitments for the state.

But, today, that new normal is unraveling. California gets a disproportionate amount of its tax dollars from high-end earners, whose income and capital gains tend to fluctuate wildly depending on Wall Street’s mood, and with wild gyrations in stock values over the past five years, along with the winding down of many pandemic-era federal assistance programs, the state is again facing a vast deficit. Best-guess estimates suggest a $56 billion hole over the coming two-year budgetary cycle, although the Legislative Analyst’s Office estimated in January that it could be as high as $73 billion.

No matter how the legislature and Governor Newsom try to juggle these numbers before the June 15 deadline for putting a budget in place, no matter the roughly $20 billion that the state is going to take from its rainy day fund, one can’t reduce a deficit of that scale without huge cuts to vital programs. Over the past two weeks, Newsom has proposed over $30 billion in cuts, some to one-time programs, others to ongoing state commitments funded during better economic moments. Cumulatively, the cuts represent more than 7 percent of the total state budget. And this at a time when California is struggling to bring its unemployment rate down in line with the rest of the country—the state has a 5.3 percent unemployment rate, compared to a national average of less than 4 percent.

K-12 education, which is always the spending elephant in the room, will of course take a significant hit, as will some of the governor’s climate change initiatives. Grants to college students will be reduced. Ten thousand vacant state jobs will be left unfilled. There will be less money for the CalWORKs financial assistance program and for homeless services.

The California Dream Alliance, an alliance of anti-poverty groups in the state, came out against these cuts last week, as did the League of California Cities. Both groups advocated increasing revenues to offset the deficit—but, wary of putting in place obstacles to growth at a time when businesses are still struggling to get hiring back up to pre-pandemic levels, the governor has, in no uncertain terms, nixed the idea of higher taxes.

Making matters worse, many cities in California are facing the same headwinds as the state itself—especially the winding down of federal programs that, for the better part of three years, pumped local, county, and state governments full of cash. This coming year, the state capital of Sacramento is anticipating a shortfall of $66 million on a budget of $1.5 billion. A much-vaunted system of free public transport for school kids will likely be abandoned, homeless programs scaled back—in a city nearing 10,000 homeless residents, environmental initiatives trimmed, and so on.

Similar stories are unfolding throughout the state. San Diego’s budget deficit is $167 million. Los Angeles’s is approaching half a billion dollars. This sense of malaise is all exacerbated by the growing woes facing homeowners. Sky-high mortgage rates have largely frozen the California market—those with low rates can’t afford to sell, and those trying to enter the market can’t afford to buy. Add in the fact that, despite all of Newsom’s pledges to accelerate and simplify home building, the state still makes it extraordinarily difficult and expensive to build new housing stock, and you have the makings of an ongoing housing emergency—putting a roof over one’s head costs far more than in virtually every other state in the country.

Further add into that mix a complete meltdown of the home insurance market over the past three years, and one has all the ingredients of a brewing crisis. State Farm recently stopped taking on new home insurance customers in the state, and a number of other large insurers look likely to follow suit. For homeowners in fire and flood zones, it has become all but impossible to get insurance, and for those able to do so, the cost has become prohibitive.

So far, there haven’t been political consequences to this triple whammy of imploding state finances, impending local government austerity, and the huge financial hit homeowners are taking because of high interest rates, the high cost of housing, and the skyrocketing cost of insurance. But if history is any guide, the political ricochet effects won’t be long in coming.

California’s legislature has had a Democratic supermajority for years, and Democrats outnumber Republicans in the state by a two-to-one margin. The state isn’t about to tip Republican anytime soon, though there has been an uptick recently in the percentage of voters registering as Republican. But the anti-incumbency sentiments that grip so much of the country in this age of angst are felt here too. Newsom’s approval ratings have taken a hit in recent months, with a plurality of voters now disapproving of his leadership. A majority of voters say the state is heading in the wrong direction. And the primary elections this past spring saw extremely low voter turnout, especially among Democratic voters—a sign of voter disengagement at a time when Democrats urgently need high turnout in order to flip US congressional seats come November.

As the budget cuts kick in over the coming months and start visibly affecting residents, that political unease and anger is likely to grow. The Democrats own virtually every level of California politics, so it wouldn’t be a surprise if a measurable percentage of angry voters start turning on the party as a new era of austerity budgeting dawns.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

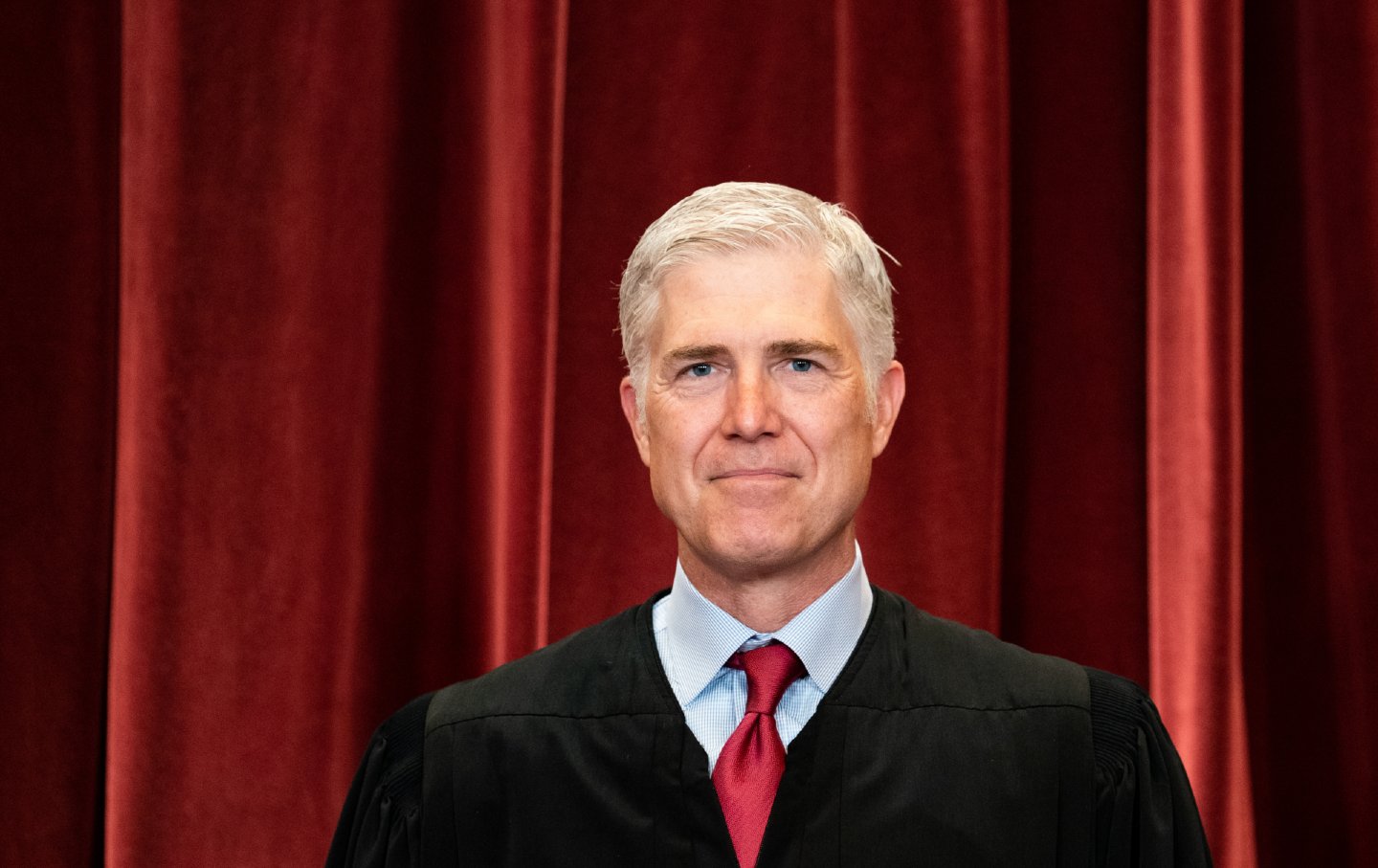

The Supreme Court v. My Mother The Supreme Court v. My Mother

After my mother escaped the Holocaust, she broke the law to save her family. Her immigration story is more pertinent today than ever before.

The Supreme Court Has a Serial Killer Problem The Supreme Court Has a Serial Killer Problem

In this week's Elie v. U.S., The Nation’s justice correspondent recaps a major death penalty case that came before the high court as well as the shenanigans of a man who’s angling...

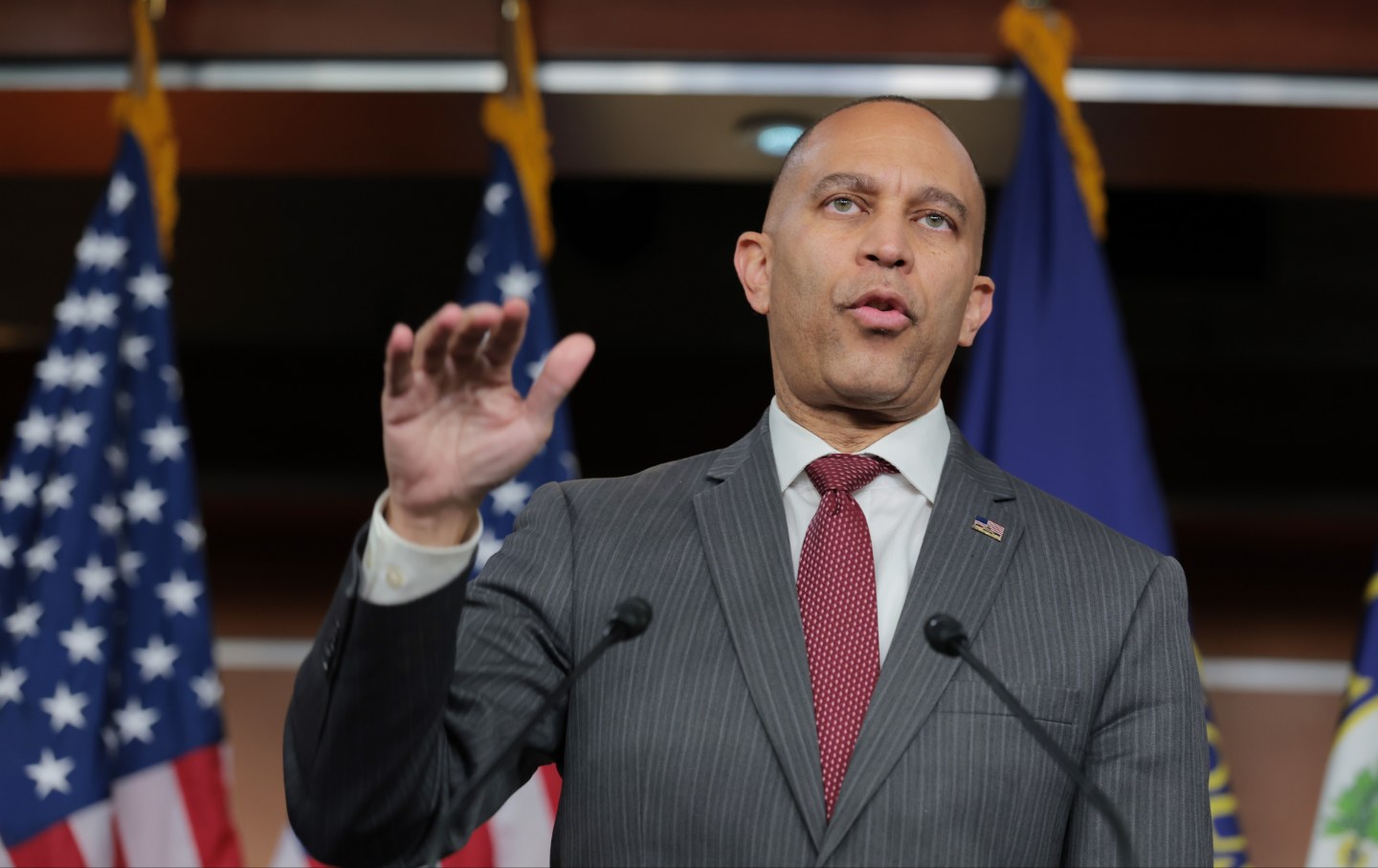

Corporate Democrats Are Foolishly Surrendering the AI Fight Corporate Democrats Are Foolishly Surrendering the AI Fight

Voters want the party to get tough on the industry. But Democratic leaders are following the money instead.

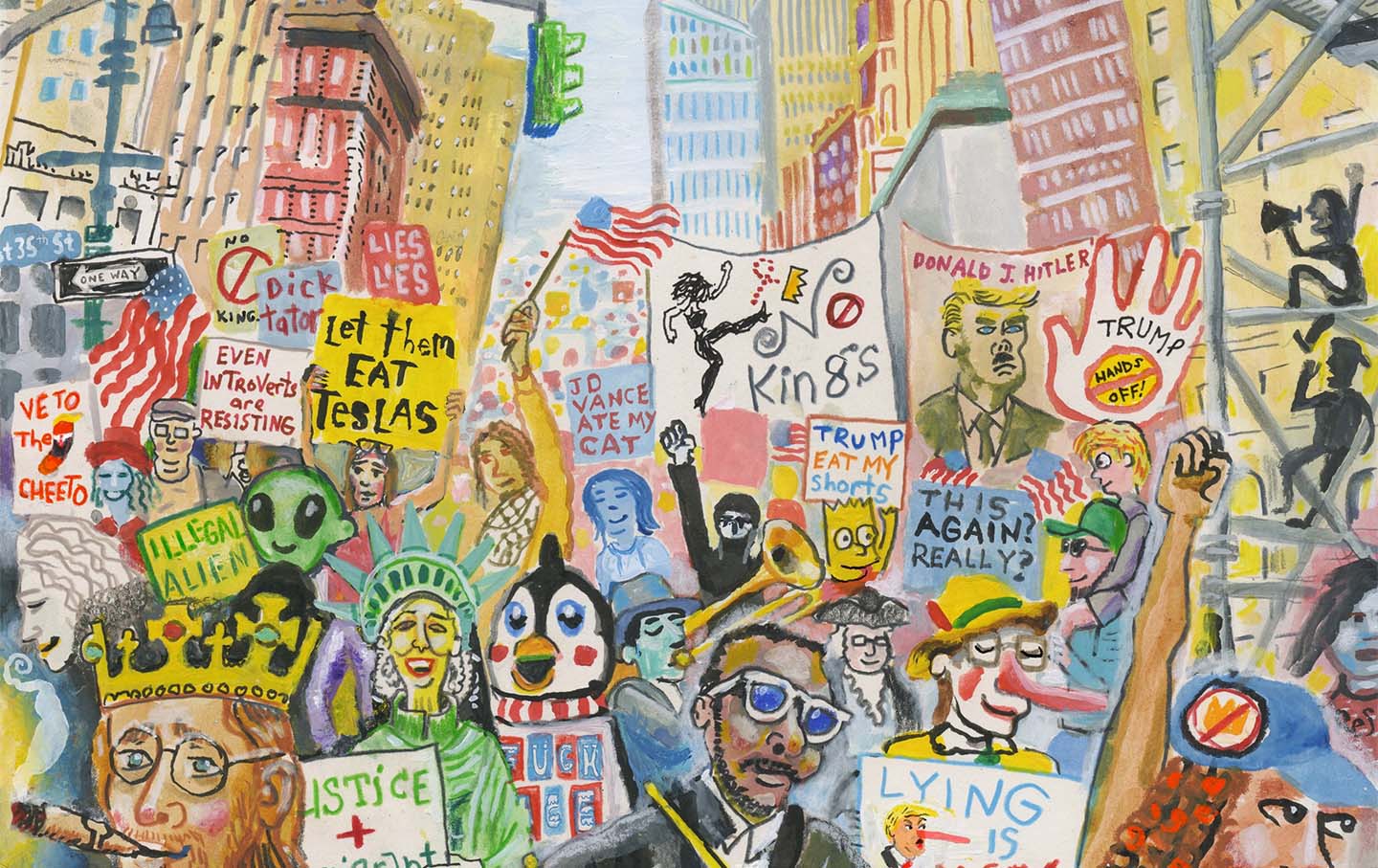

Marching Against a Corrupt Regime Marching Against a Corrupt Regime

People taking to the streets for democracy.

Keeping the Police Out of Pregnancy Care Keeping the Police Out of Pregnancy Care

We must be vigilant in keeping law enforcement out of exam rooms.