With the 2018 midterms behind us, politicians can start campaigning for the next big election: the one that leads to the White House. But before Democratic hopefuls reach the general election in 2020, they will have to make it through the primaries. With two likely candidates floating high-profile proposals with similar aims, the Democratic race seems officially under way.

Senator Kamala Harris of California put forward what she’s calling the LIFT Act, which would increase tax credits for low- to moderate-income families. And New Jersey’s Senator Cory Booker introduced a bill to seed every American child with a savings account of $1,000 that would grow until they reach age 18.

Both plans would funnel money to American families, especially those who have the least, and offer relief to millions. But they miss an opportunity to help families in the easiest, most streamlined way: by just writing them checks.

Harris builds on the existing earned-income tax credit by offering up to an additional $3,000 a year for an individual or $6,000 for a couple, phasing it out once people with children start earning $100,000 a year. Families could get the money as a lump sum at tax time or in monthly payments.

Booker also wants to give families money, but his plan locks it away for later. At birth, every American child would get a savings account with $1,000 in it, and the government would add up to $2,000 each year, depending on the family’s income. Once those kids turn 18, they could use it for allowable expenses, such as college or a mortgage down payment.

Both ideas attack economic inequality, particularly for black families, by putting government money directly into the hands of those who need it. Still, they are not as direct as they could be. Harris’s plan suffers from two problems. The first is who she leaves out. By matching only the income that poor families earn from work, it omits those who don’t earn anything. There are an increasing number of families who have neither income from work nor cash assistance from the government and who would miss out entirely despite living in deep destitution. At the same time, she excludes better-off families, even though the costs of raising a child are steep for them as well. Universal programs also tend to be more politically resilient thanks to the wide buy-in. The second problem with Harris’s plan is that she still relies on giving money to families through the tax code, an opaque and complicated way of doing it.

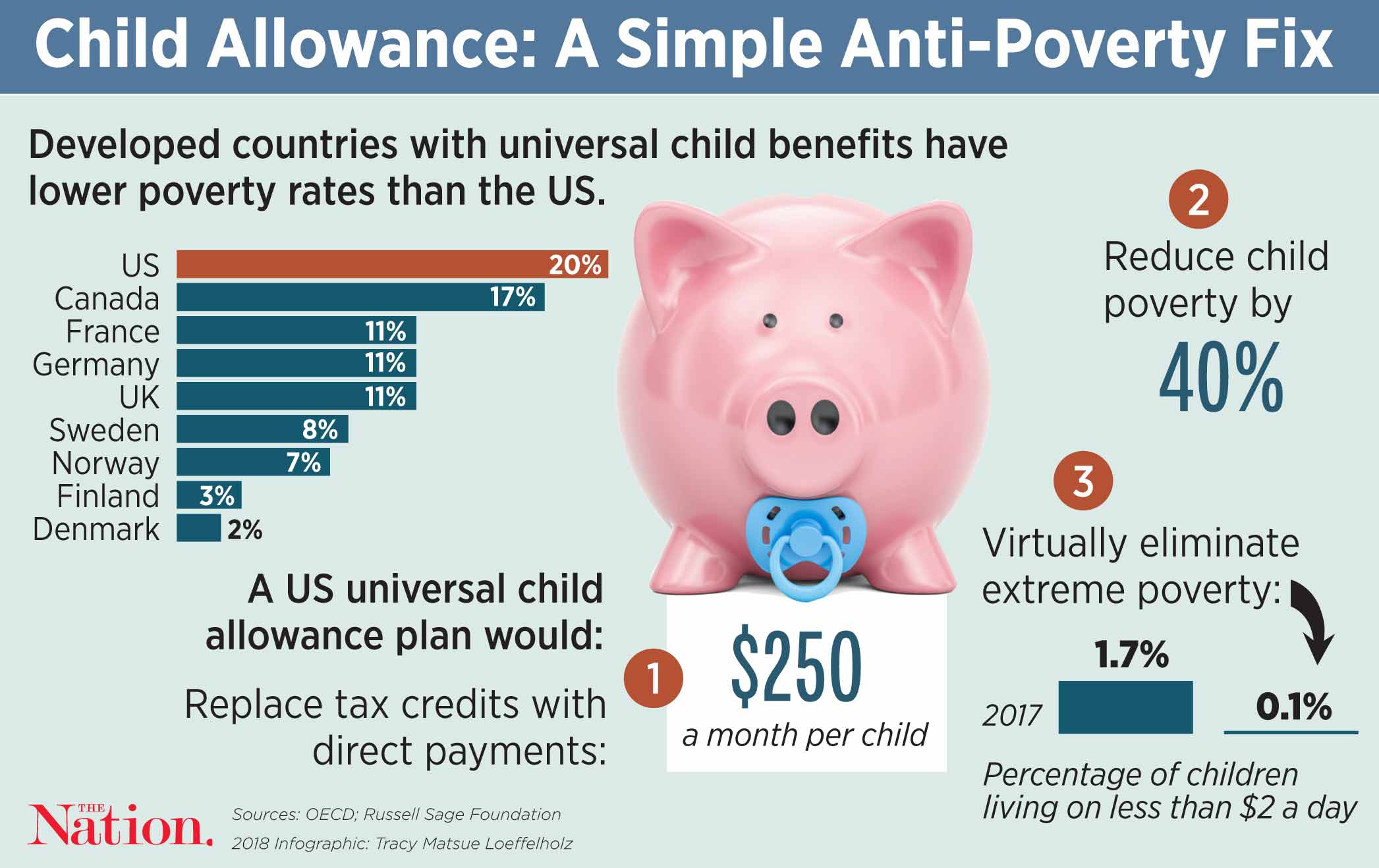

Booker gets around this by sending money straight to the people who need it, but not at the time when they need it most. Families suffer huge drops in their income when they welcome new children; a household with two adults loses, on average, $14,850 when they have a child, or about 14 percent of their income. That’s enough to throw a sizable share of families into poverty. Even after taxes and government benefits, one in five American children lives in poverty—a rate well above that in most other wealthy countries. Once children get older, that financial pressure eases. Booker’s proposal would erode the wealth gap between rich and poor and white and black, but it mistimes the assistance, providing it when most families are more economically stable.

The most straightforward answer is a child allowance, something that already exists in at least 12 other developed countries. Ten researchers at the Russell Sage Foundation proposed an approach that would give all families with children a monthly cash benefit. They would replace existing tax credits for parents with at least $250 a month for each child, paid out in a fashion similar to Social Security benefits. Under their most bare-bones proposal, child poverty would fall by 40 percent, with extreme poverty, or children living on just $2 a day, all but eliminated.

That plan may be simple, but it’s not cheap: Its proponents estimate that it would cost $190 billion a year. But that’s still less than what’s been estimated for Harris’s plan, and less than the recent Republican tax cuts are likely to cost over the next three years.

It would be money well spent. As Democrats start laying out their messages for 2020, many of them are thinking big. It would be useful, though, for them to think simple and direct, too.

Bryce CovertTwitterBryce Covert is a contributing writer at The Nation and was a 2023 Reporter in Residence at Omidyar Network.