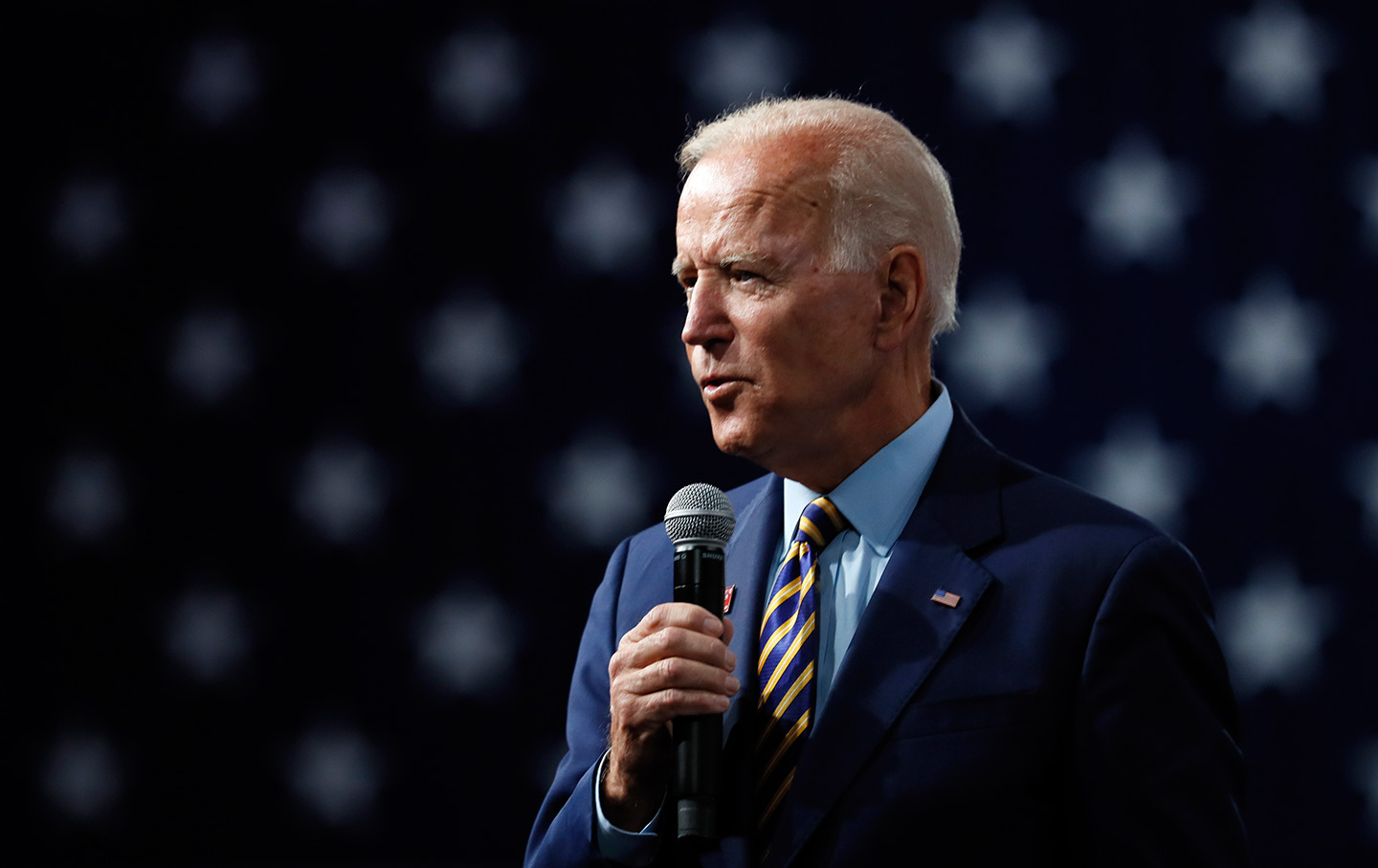

Democratic presidential candidate and former vice president Joe Biden speaks in Des Moines, Iowa, on August 10.(Charlie Neibergall / AP Photo)

Among the things revealed by CNN’s seven-hour climate crisis town hall with the 2020 Democratic presidential contenders is that organizing works. Earlier this year, activists with the Sunrise Movement began agitating for the Democratic National Committee to hold a climate debate. While they didn’t get an official debate, they did get a prime-time, science-based, and mostly substantive discussion of climate change. Years of work by activists to elevate climate change to the top of the political agenda resulted in every candidate agreeing on a certain floor for action, including reaching net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 at the very latest, ending federal subsidies for the fossil fuel industry, and restricting oil and gas leasing on public lands—something the Obama administration resisted.

But there is still plenty of fraught territory, notably around how candidates plan to accomplish the ambitious goals set out in their climate plans, and their willingness to directly confront fossil fuel corporations, specifically around the issue of fracking and natural gas. Despite a growing body of evidence of the dangerous climate impact of methane leaks, natural gas is still a tether to the fossil fuel industry that some Democrats seem reluctant to sever. One question a few hours into the town hall went straight to this tension. “How can we trust you to hold these corporations and executives accountable for their crimes against humanity,” Isaac Larkin, a 27-year-old PhD candidate at Northwestern, asked Joe Biden, “when we know that tomorrow you are holding a high-dollar fund-raiser hosted by Andrew Goldman, a fossil fuel executive?”

Larkin was referring to a story published a few hours before the town hall by The Intercept, reporting that Biden was due on Thursday at a fundraiser cohosted by Goldman, who cofounded a natural gas company called Western LNG. Biden, who has signed a pledge not to take contributions of more than $200 from fossil fuel executives, was caught off-guard by the question. “Well, I didn’t realize he does that,’’ he responded, referring to Goldman, who was identified in one 2018 filing as “a long-term investor in the liquefied natural gas sector.” As Biden and moderator Anderson Cooper both clarified later, Goldman is not technically an executive at the company. “He was not on the board, he was not involved at all in the operation of the company at all. But if that turns out to be true, then I will not in any way accept his help,” Biden said.

It was a slippery, evasive response—if technically accurate—from Biden, who struggled to articulate a clear vision for climate action throughout his portion of the town hall. Speaking about the need for the next US president to spur other countries to act, Biden repeated a right-wing talking point about the United States’ being responsible for “only 15 percent of the problem,” a point that omits the responsibility this country bears as the world’s biggest carbon polluter historically, as well as the US role in driving technological innovation that can be adopted elsewhere. On fracking, Biden said that rather than trying to ban the practice nationally (something that Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, and a few other candidates have called for, though a president can’t do that unilaterally on private land), he favored no new wells on public lands. He claimed that the Obama administration didn’t do more on climate because the urgency of the climate crisis wasn’t well understood until recently, when in fact scientists and advocates have been sounding the alarm for decades. “Everything is incremental,” Biden said at one point, dodging a question about fossil fuel exports.

The problem with incrementalism, of course, is that it’s incompatible with science indicating that we’re rapidly running out of time to take action. Biden did allude to that reality towards the end of his segment (“We have to act now. Now.”), and it was refreshing to hear him talk about the “enormous opportunity” to create good jobs through climate action. But overall his often rambling, unfocused responses raised rather than answered questions about his commitment. Substantive action requires directly confronting one of the most powerful industries in the world—not relying on their representatives to raise funds or to provide climate policy advice.

A number of candidates offered bold answers to tough questions. Kamala Harris joined Warren (and, previously, Washington Governor Jay Inslee) in calling for an end to the filibuster if Republicans use it to block climate action in the Senate. Cory Booker, filling the unenviable last slot, discussed some of the ways the chief executive could take action without Congress, such as through trade policy. Sanders spoke powerfully about the stakes of the climate crisis, and discussed accountability for fossil fuel companies who’ve misled the public on climate science, saying he’d direct his Justice Department to investigate them. He also spoke about the need for a just transition for workers. “Let me be clear: The coal miners in this country, the men and women who work on the oil rigs, they are not my enemy. My enemy is climate change,” Sanders said.

Elizabeth Warren, who was at least twice as awake as anyone who’d watched the five hours leading up to her segment, returned repeatedly to the corrosive influence of the fossil fuel industry and the corrupt political system that props it up, refusing to be distracted by questions about light bulbs and consumer choice. “The first thing we’ve got to do is we’ve got to attack this corruption head-on in Washington and say enough of having the oil industry, the fossil fuel industry, write all of our laws,” Warren said.

That influence won’t just fade on its own: Democrats have to actively work to sever the ties. As the town hall revealed, the politics of climate change are finally shifting. But fossil fuel interests are nimble, too. Already, industry representatives are morphing their tactics from outright climate denial to attempts to undermine climate action by putting forward nice-sounding but ultimately milquetoast policies. Elizabeth Warren nodded to this threat during the town hall, warning that Exxon could soon be underwriting purported climate policy. The plans will sound good, she cautioned, but “Read the fine print.”

Zoë CarpenterTwitterZoë Carpenter is a contributing writer for The Nation.