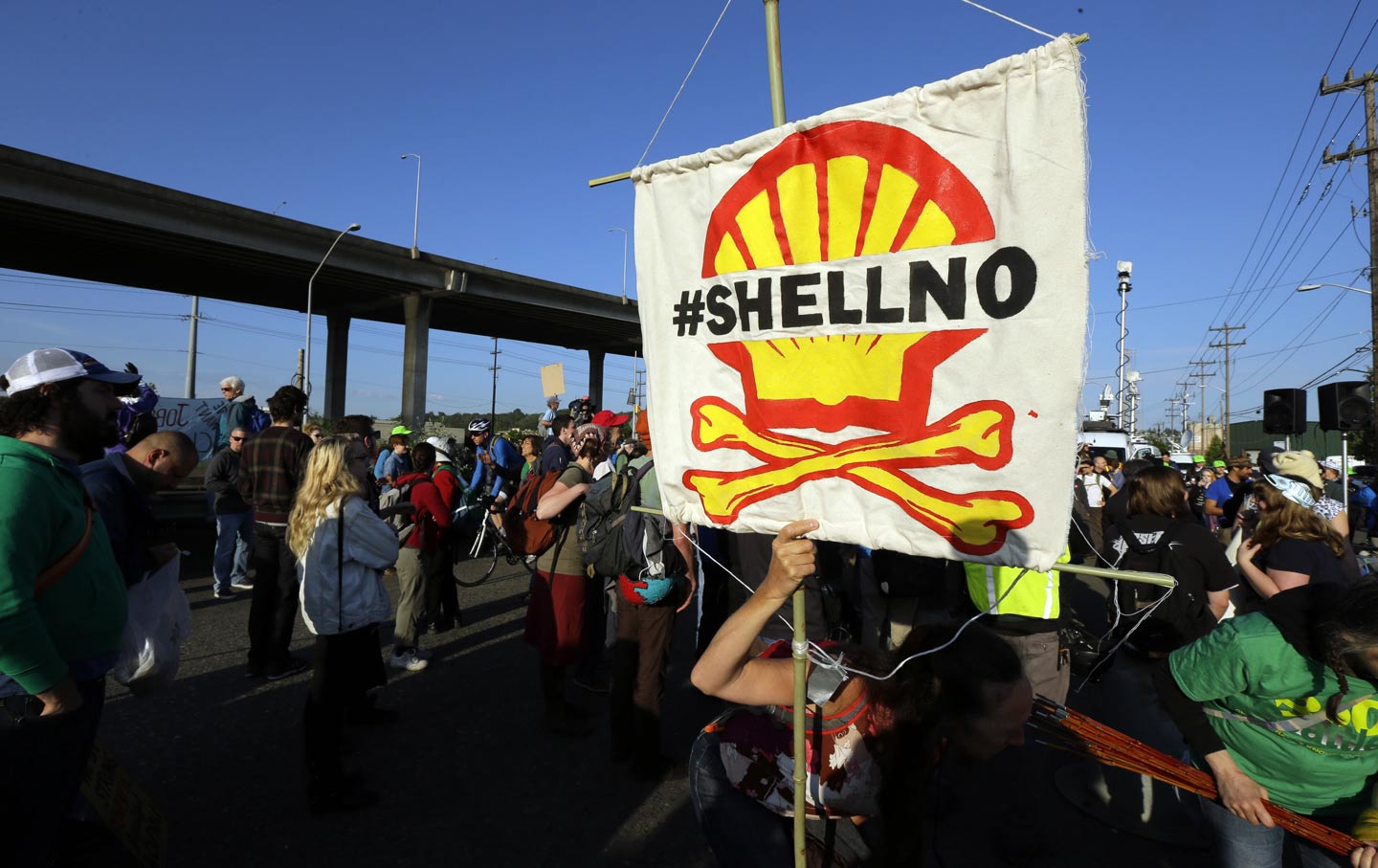

Protesters rally at the Port of Seattle, Monday, May 18, 2015, opposing Arctic oil drilling and a lease agreement between Royal Dutch Shell and the Port to allow some of Shell’s oil drilling equipment to be based in Seattle. (Ted S. Warren / AP Photo)

Unexpected things tend to happen when Ken Ward goes to trial. In 2014, he and fellow climate activist Jay O’Hara, having blockaded a coal tanker with a 32-foot lobster boat at Brayton Point in Massachusetts, saw their felony charges dropped and the district attorney join their side.

On January 30, in a courtroom in Skagit County, Washington, Ward—deputy director of Greenpeace USA in the 1990s and former president of the National Environmental Law Center—stood trial on felony charges for safely, nonviolently shutting down Kinder Morgan’s TransMountain tar-sands oil pipeline. Though he faced up to 20 years in prison, Ward did not contest the facts of his case—indeed, he and his defense team provided a video of his action. Nevertheless, though Ward was denied the use of a “necessity defense” by the presiding judge (who during a pre-trial hearing had cast doubt on settled climate science), the jury was unable to reach a verdict, and a mistrial was declared. It was a stunning outcome, hailed by Ward’s supporters far and wide as a victory of conscience. The prosecutors have decided that Ward will be retried, with the new trial date to be determined.

Ward, 60, was one of five nonviolent protesters who on October 11 of last year, with the support of the Climate Disobedience Center (co-founded in 2015 by Ward, O’Hara, and fellow activists Marla Marcum and Tim DeChristopher), turned the emergency block valves on pipelines in Washington, Montana, Minnesota, and North Dakota, successfully shutting down the flow of tar-sands oil into the United States from Canada. Reuters reported that the action “shook the North American energy industry,” calling it “the biggest coordinated move on US energy infrastructure ever undertaken by environmental protesters.” All five face serious felony charges, as do two members of their support team. One of the documentary filmmakers who captured the action in Minnesota faces misdemeanor charges, and filmmakers covering the other actions faced charges that have since been dropped.

“Valve turners” Emily Johnston, left, and Annette Klapstein shut down Enbridge Line 67 in Leonard, Minnesota on October 11, 2016.(Steve Liptay)

Following Ward’s trial, I talked at length with him and another of the “valve turners,” Emily Johnston, a poet and core organizer of the grassroots 350 Seattle. Johnston, 50, is scheduled to go to trial next month in Minnesota, where she faces up to 20 years. She met Ward around the time of the “Delta 5” climate direct action near Seattle, which also led to a “necessity” trial. And they worked together on the dramatic #ShellNo protests in Puget Sound and in Portland, Oregon—where Johnston joined Ward in an 18-foot dory they attempted to anchor in the path of Shell’s Arctic ice-breaker Fennica.

“We have to shut it down,” Ward told me in May 2013, a few days before he and O’Hara anchored their lobster boat at Brayton Point Power Station (described in a July 2013 feature I wrote for The Nation, later expanded in a book). Not a bad rallying cry for serious resistance in the time of Trump. (The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Wen Stephenson: What’s your interpretation of what happened in that courtroom, the outcome, and how the trial was conducted?

Emily Johnston: It’s heartening. We all expected a conviction on at least one of the counts [burglary, sabotage], given Ken’s clear admission that he’d done it, and the video evidence and everything else, yet without being able to present the necessity defense. So it’s exciting that the jury didn’t convict. It shows how civil disobedience actually can advance the law. Because, whether it’s jury members or members of the public, people see that something much weightier than a broken law is at stake. It’s clear to me that public awareness of climate change, and also Ken’s testimony about his own context and his history—how much he’s done, for decades, to try to be effective—made enough of an impression that somebody said, I’m not going to convict, period.

Ken, you were the guy in the dock. What’s your takeaway?

Ken Ward: When it went to the jury, my idea of a good outcome was that I would be convicted, certainly on one, probably on both counts, but that I would see at least one or two jurors feel bad about it—come over to us, maybe have a few tears in their eyes, maybe be willing to say in public that they really wrestled with this. That struck me as an ideal outcome. So, as I’ve said, I was astonished.

Ken Ward after shutting down the TransMountain pipeline in Skagit County, Washington, on October 11, 2016.

And the thing that I keep coming back to, and partly this is because I’m on jury duty next week.

Wait. Seriously?! [laughter]

KW: I can tell you this, the only down side I can think of, having not been convicted, is that I have to go do jury duty. [laughter] If I had been convicted of a felony, I would be excused from jury duty, but because I’m not convicted of anything, I still have to go sit in the damn room, even though nobody’s going to put me on a jury.

But as a prospective juror, I was sitting there thinking, OK, what would I do about this? Bottom line is, there were three things we sent them back to the jury room with. First, we offered, and the prosecution accepted, our seven-minute highlight video of the action, showing me doing it. So they have that. There’s no question about what I did. Second, they have the NASA chart of CO2 concentrations going back 400,000 years, all the peaks and valleys showing it never even reaches 300 [parts per million], and the current concentration at 404 ppm. And third, they have the sea-level map [using the Climate Central online mapping tool] of Skagit County in 2050, with five feet of sea-level rise. And that’s a conservative number. It shows all the low-lying lands in Skagit, which are tulip fields—the biggest agricultural product around there is tulips—and all the tulips are underwater, and it shows all the refineries becoming islands. And that’s it. They had those three visuals: me doing it, the CO2, and sea-level rise.

And you had a mistrial, a hung jury. What does it mean?

KW: Well, at least some of the jury agreed with us that avoiding climate cataclysm is a more important problem than enforcing the letter of the law. We did not get exactly what I wanted, because we were not able to offer the necessity defense. But bottom line, the jury was presented two possible stories here: They were presented with the choice between cataclysm and the simple, normal application of the law. And some of them saw a greater need.

Was it, then, a de facto necessity trial?

KW: No, I don’t think it qualifies as that, because to be a necessity trial, you have to be able to actually articulate the legal concept of the necessity defense. This was, arguably, a more powerful result than winning in a necessity defense. Because in a necessity defense, we’re saying to the jury: Here’s a legal thing you can do; this is a reasoned part of the law; you have to meet these requirements, but once you do that, then it’s OK, you can agree that he did it, and you can set those things aside. It’s entirely appropriate and legal, it’s part of our law. Here, they were given no indication that they could do that—and yet they did it anyway. If necessity had been included in the jury instructions, then it would have been a very different conversation in the jury room. Here, they had to assert a thing that they had some idea was the right and the fair thing to do, without any backing from the judge and the courts. I think it’s far more powerful.

A lot has changed in the world, at least politically speaking, since you took your action in October. Would you do it again?

EJ: Yes. Presidents come and go, but the physics are the same. It’s necessary. Might we pay a higher price for it than we expected? Yes, we might. But it is absolutely necessary. There are any number of other Hail Mary passes that we have to make, in terms of what might actually shift the political landscape enough to get people on board demanding action on climate, and this is one of those things, conceivably. Historically speaking, nonviolent civil disobedience is one of the few things that ever has done that. So we have to try.

KW: The answer is yes. That doesn’t mean there haven’t been times when I’ve worried about the question. For me, what it comes down to is, well, is there something else I would’ve done instead of this? And the answer is always, so far, I can’t think of anything more effective I’d do. So, yes, I’d do it again.

The word “resistance” suddenly has a great deal more currency. One might ponder what it meant before the election, and what it means now, but one of the immediate effects of the election was to send a chill through a lot of activists. What would you say to people who may have been willing to engage in nonviolent direct action before the election, but are now, understandably, freaked out by the new political atmosphere?

EJ: Well, it depends entirely, because there are levels of risk, even in this new reality, and there are other things people can do that are effective, as part of the picture.

I’m speaking as one of the organizers of the Pacific Northwest Pledge of Resistance, where we’re training people to engage in civil disobedience in the Puget Sound region—we were hoping to get a thousand this year, and we’re already up to 1,600, and by the end of the year we hope it’ll be several thousand. And I feel really responsible for thinking about this carefully, when we’re talking about civil disobedience, so I have mixed feelings. But I do not have mixed feelings about the necessity of civil disobedience. It is still necessary. It is maybe far more necessary than ever, arguably. Some people will pay a high price for that, so I don’t take it lightly at all. And I would be cautious in who I’d encourage to do what. I would hope that people will take very seriously the risks, that they’ll think about what those risks really are these days. And think about what’s likely to be most effective. Because we don’t want a lot of good people to end up in jail for years, especially if it doesn’t end up making a significant difference.

Maybe I’m wrong that there was a chill. What do you see, being deeply involved in grassroots organizing in Seattle?

EJ: Yeah, chill is not the word I’d use. We’ve had thousands of people signing up for our mailing list, wanting to come to our new-member summit and our pledge-of-resistance summit. Our mailing list went from about 3,000 in September to 6,000 now. It doesn’t mean everyone wants to do civil disobedience, but they’re fired up, they’re horrified, and they’re totally ready to throw down.

KW: I do think there’s a distinct shift in who the people are who are signing up. I think there are a lot of people who’ve wanted to engage in direct action as long as it’s pretty non-risky, and we’ll lose a lot of those. But I think I’m seeing and hearing from people, smaller numbers, but who are much more moved to say, OK, I really am willing to do this—even because the risks feel higher. And I don’t think we need large numbers of people, in the kind of efforts we’re looking at, to significantly shift the politics on this. We’re not talking about huge numbers.

Ken, you commented recently that if our response to the current situation, meaning the climate situation, is to march in the streets and hold placards, those in power—the Rex Tillersons—will just laugh. You’ve said many times, we’re in an emergency situation and we need to act like it. But, of course, your action was taken before the election. What has the election changed, if anything, and does it affect the way you view your action now?

KW: In terms of the climate, everybody around here since the election has been in some kind of weird emotional state. I was completely out of it during the month of December. But unlike a lot of people, I was depressed because I thought we just saw a convincing repudiation of the asinine climate strategy that mainstream US environmentalists have been following, and maybe now we had an opportunity to have a different conversation about what to do, and I didn’t see any change.

I think the climate has far more to do with the election of Trump than anything that’s being discussed. It gets lost. As always in politics, follow the money, right? In the actions that the Trump people have taken, and who they’ve appointed, if you ask who benefits the most from all this, it’s all fossil fuel. It’s the fossil-fuel industry who are making the money here.

EJ: Historically speaking, the environmental movement—prior to the climate movement, because there wasn’t really a climate movement until 350 came along—was too comfortable and too cozy, and not remotely aggressive enough. But I think a lot of people in the actual climate movement, as opposed to the broader green/enviro movement, have taken this as a point of fact for a long time now—Naomi Klein’s book [This Changes Everything] made it explicit in various ways. And so the part that a lot of climate people are coming together around, is that we have to be a lot more aggressive, we have to be uncompromising, we can’t go along to get along and think that making incremental progress is somehow acceptable. Because this is no longer an incremental problem.

To my mind, the failure around climate is very similar to the failure around the Clinton campaign—which is, that by being so centrist, they absolutely inspired nobody. There is a world of people out there who, even though they don’t read about climate obsessively, really suspect in their bones that it’s catastrophic, and they feel paralyzed by that knowledge and therefore just look away. Because for a long time nobody was providing them a legitimate alternative to looking away. I think people had an instinct that this incremental stuff wasn’t going to work. On the one hand, they wanted to leave it to other people—they somehow thought there were grownups who were taking care of this for them, and therefore they didn’t need to worry. And on the other hand, their instincts told them it wasn’t true, that it is catastrophic, and, “Oh my God.” That was a really good recipe for paralysis. And they were not being inspired. The main thing I’ve always found inspiring about Bill McKibben is his complete unwillingness to prettify the story—his willingness to say, this is how bad it is. He was one of the few people doing that, and that was why I trusted him.

From the climate perspective, there may be a sort of silver lining in the election, in that it’s clarifying—that is, it clarifies a lot of things, including the pre-existing fact that the fossil-fuel industry effectively runs US energy policy. Now we’ve got Rex Tillerson as secretary of state, but ExxonMobil has effectively been in charge for decades.

EJ: Yeah, totally. There’s a level at which this clarifies it for people who thought we were being too cynical. I think a lot people are suddenly, like: Whoa, no, that’s not too cynical, that’s absolutely the case. And it’s really terrifying for them.

I think this is part of what Ken is saying, namely, ExxonMobil has been effectively in charge for decades—with the complicity of a whole lot of people who claim to care about climate change.

KW: Yes, and I want to clarify something I was saying earlier. We—US environmentalism—made a decision fifteen years ago not to put out the truth, and also not to contest for the hearts and minds of people on this matter, especially in the center parts of the country. I wrote something semi-facetiously, I think in 2005, that we really ought to shut all of our environmental organizations’ offices, hold a press conference on the steps of Congress, and announce that we can’t possibly do anything in Washington since the fossil-fuel companies own the government, and then march away, into the center of the country, and debate the question there.

In our failure to do that, what we thought we could do instead was to lie about the problem, negotiate with the fossil-fuel companies, and come up with a technocratic policy solution around the margins, without ever actually contesting it. That same set of complaints, acting like that, is central to what the Trump voter is pissed about: that fucking technocrats, on the coasts, without ever talking to us, are going to impose a bunch of stuff. I mean there’s a very powerful story out there, and this is central to the Trump experience.

Journalists still ask, “But are protests really effective?” Emily, in a recent post [linking climate direct action with the Standing Rock struggle and environmental justice protests on the Gulf Coast], you cited a new book called This Is an Uprising: How Nonviolent Revolt Is Shaping the 21st Century, by Mark and Paul Engler. I feel like recommending it to my old mainstream journalist colleagues as a sort of remedial education on social movements. Can you explain why you referenced that book?

EJ: The book looks at different movements [including civil rights, women’s suffrage, marriage equality, and others] and how they worked, and how they often appear to have been moments when all of a sudden everything changed—and it argues that what people don’t see is how much work was leading up to those changes.

There’s a local reporter in Seattle who’s basically on our side, but likes nothing more than to make fun of protests. But like most mainstream journalists, he’s very respectful of the civil rights movement. When something is deep in the rear-view mirror, and they can see the impacts that it had, and they can see how it built up to various changes, then they can respect it. What they have a hard time with is seeing the careful thought that goes into a movement in its beginning stages, its middle stages. They don’t understand that it was important that we got out in the kayaks out in front of the Shell rig, because we only stopped it for an hour and a half. Well, the truth is, when Shell stopped its Arctic drilling program, one of the board members said, yes, we were disappointed by what we found [in exploration], but also, we were acutely aware of the reputational risk. He was talking about us. If there had been no protests in Seattle and Portland, there would’ve been no risk to reputation.

And we never really know what the immediate or longer-term effect will be. That’s just the way it is.

EJ: Yeah, and coming just four or five months after our actions in Seattle, that was a real gift, in that we got this explicit acknowledgment that we helped create those conditions. You don’t always get that gift. You just have to, in good faith and in as careful and considered a fashion as you can, you have to be willing to take the risks—and think, well, what’s going on now is not working, so let’s try this. And you can’t know in advance. It’s like when people go off to war, and leave their families behind, and know that they might get killed. Do they only do that if they know for sure it’s going to be successful? Of course not. They do it because they think it’s the right thing, and think it might make a difference, and they can’t live with themselves if they don’t do it.

When you referenced the Englers’ book, you referred to the “moment of the whirlwind.”

EJ: Right. There can be all this work that builds and builds, and then all of a sudden, something changes—whether it’s political, in this case, or purely social, all of sudden everything is up for grabs, and there’s a wholly different kind of energy. And it’s possible to use that energy, especially if you’ve done the work ahead of time. And I think we are totally in that kind of moment now. I actually think that in this case, it’s going to be an extended moment, lasting years, where there will be waves of these moments of the whirlwind. It’s all of the energy that we’re seeing flow into our movement. And you know, look at what happened at the airports the other day. They had something very specific to do, and all of a sudden, everyone just showed up. But people were also, in any number of ways, ready to show up. It didn’t happen out of nothing. But when you’re ready, and when you’ve been doing the planning and making the connections, and talking to people about the risks and that kind of thing, and a moment like that presents itself, then things can cohere in a really remarkable way.

Ken, do you see it that way?

KW: I think it’s best to think of this in straight concrete terms. We have to elect someone other than Trump in four years. Who is that person, and what is their mandate? My worry is that just throwing climate into the pile with every other issue that’s out there, in one grand resistance movement, means we lose climate. We need to elect somebody in four years who is elected on climate—to do what is necessary. And I don’t see how we do that by just being one of the various things in response to what Trump does. That’s the question we have to ask. How do we make that happen? It’s really, really easy to see us electing a Democrat who has climate just exactly where, or maybe one notch up from where, Clinton had it.

Bernie was better than just about anybody on climate, but even he didn’t make it his number-one thing.

KW: He was the best under the old paradigm, that is absolutely the case. And there will be another paradigm, but not necessarily the solution paradigm, just a better losing paradigm.

EJ: I disagree with Ken here. This whole notion, among a lot of folks, that by combining everything we’re diluting it too much, by including all this other stuff—I think the Bernie example is 100 percent right, in that our job is to inspire people.

Given the physics of the climate—because the world is quite literally going to go to hell if we don’t change things really quickly, and because it’s still going to go to hell even if we do—what I think is really important is that we have a choice between a world that is radically changing and is terrifying socially and politically, just horrible and inhuman and inhumane, or we have a chance to fight for a world that’s a decent world, where people are doing all they can to change the physics, and the immediate problem of fossil fuels, etc., but where that’s not our only job. We also have to manage, for example, insane amounts of mass migration and refugees. I’m not saving this world just because I want it to be a little less hot and have there be a handful fewer people suffering, or a handful fewer species going extinct. It’s because we have the choice between a decent world and a world that’s completely inhumane. And so by connecting the issues, especially around refugees and migration, we can make it clear that we’re going to face the gravest crisis that we’ve ever faced as a species, but that we can do so in a way that’s honorable.

I always ask people what they’re fighting for. What would you say you’re fighting for?

EJ: I really love this world as it exists. And we are losing this world. I feel personally responsible, as an American, that other people are suffering and that other species are suffering. It’s all of these things. And I don’t feel that inaction, looking away, is moral. I feel connected to everything around me in the world. We are absolutely connected to everything else on this beautiful planet, and yet we are killing it, and we are killing ourselves. I can’t even look out the window without thinking about that. When it’s a gorgeous day, part of me is thinking, Oh, what a gorgeous day. And another part of me is thinking, what a world to destroy.

KW: I am fighting for all the reasons Emily said, and also because I happen to think it’s a better way of life, to be doing what I’m doing, as opposed to the alternatives—which would require on some level that I disengage from reality. My hero Vaclav Havel said something about “living in truth.” You remain engaged with the reality of what is happening, you don’t hide yourself from the pain and the suffering of it, and you do the best you can to address it. And living in that way is really what we’re called to do. Short of that, it means you’re living in ignorance, and more pain and despair. So as painful as it is, I prefer to stay tightly connected to reality, and then act appropriately. And for all of the downsides, it’s a better way to live. I don’t have any regrets.

Wen StephensonWen Stephenson is the climate-justice correspondent for The Nation. An independent journalist, essayist, and activist, he is the author of What We're Fighting for Now Is Each Other (2015), about the pivotal early years of the US climate justice movement. His new book, forthcoming from Haymarket in June, is Learning to Live in the Dark: Essays in a Time of Catastrophe.