In Stories We Tell, actor turned director Sarah Polley interrogates her past, revealing that our stories are our dearest form of property.

Akiva Gottlieb

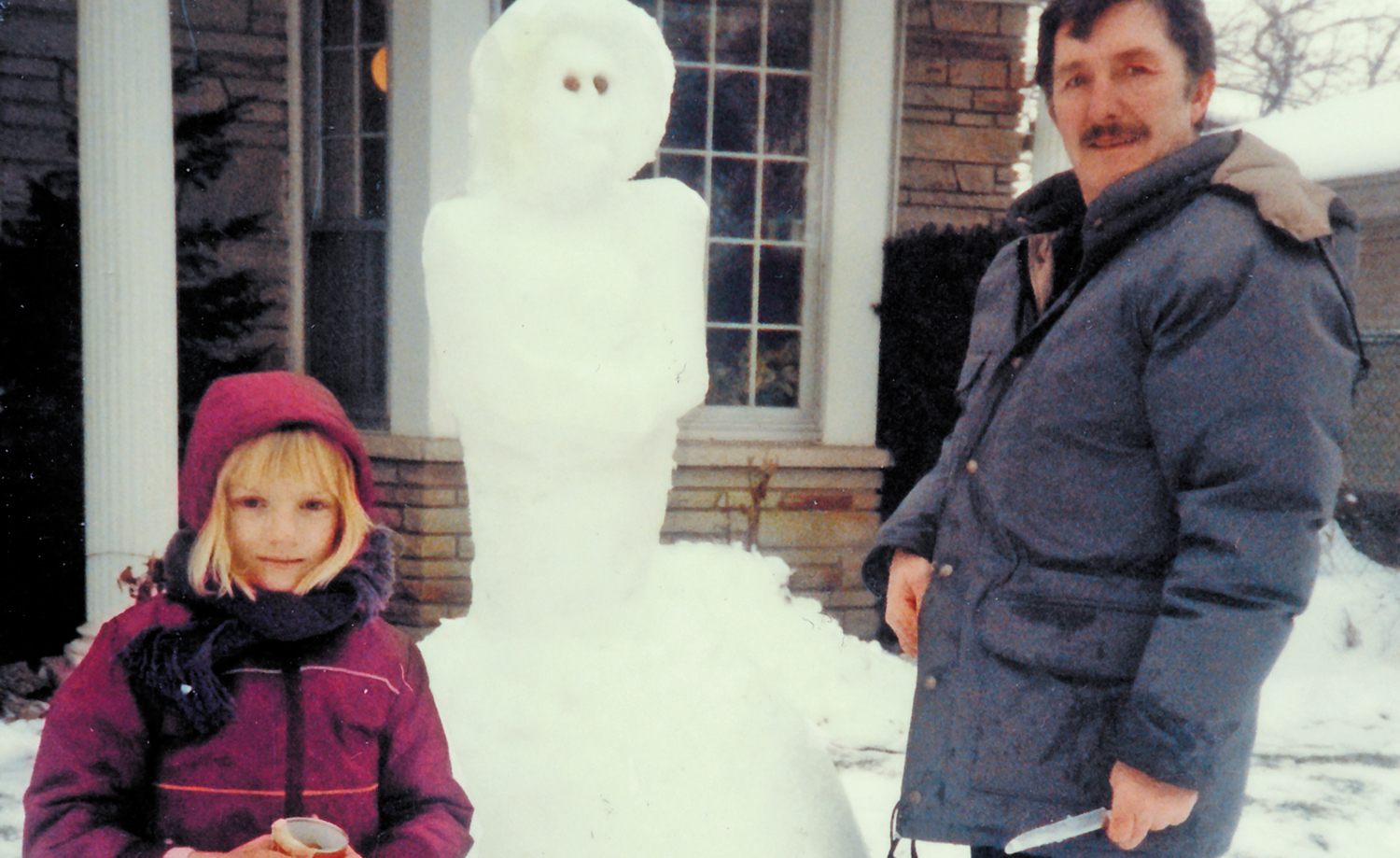

Sarah Polley and Michael Polley in Stories We Tell

The actress Sarah Polley generally comes across as smarter than the films she’s in. Her performances keep something in reserve, radiating intelligence without generating heat. Even when playing the lead, which she does too infrequently, Polley keeps a low profile. In magazine interviews that invariably mention her resistance to the trappings of celebrity, she has described herself as having been “really cynical about acting,” and her sidestepping of emotional abandon often creates extra-narrative tension. Hers is a strangely communicative detachment, one that flatters the attentive viewer from a distance.

Born in 1979 to two Toronto actors—on whom more later—Polley began performing in her youth, appearing as the pint-sized comic heroine of Terry Gilliam’s swashbuckling The Adventures of Baron Munchausen and in the Canadian television series Ramona and Road to Avonlea. But she found herself exiled from the Disney Company’s good graces after wearing a peace-symbol necklace to an awards show during the Gulf War. At age 14, she dropped out of school to take up political activism—even losing a couple of teeth in a local protest—and then appeared in Atom Egoyan’s two greatest films, Exotica and The Sweet Hereafter. Polley’s performance in the latter, as the paralyzed survivor of a school bus accident and potential star witness in a class-action lawsuit, is unflinching and unforgettable: she turns from paragon of innocence to calculating liar to moral beacon without a twitch, grin or grimace. If she has often been cast as a victim, it’s because she registers many types of flatness without exposing the seams.

Though Polley has chosen her roles carefully ever since then, working with art-house royalty like Kathryn Bigelow, David Cronenberg, Hal Hartley and Wim Wenders, she has often turned in the only distinguished performance in their most undistinguished features. In more mainstream productions, such as Doug Liman’s rave-culture black comedy Go or Zack Snyder’s remake of Dawn of the Dead, Polley appears to have wandered onto the set by mistake. Her decision to turn down the role of Penny Lane in Almost Famous could be called a serious error—especially since it earned the incomparably bland Kate Hudson an Oscar nomination—but it’s difficult to imagine Polley’s pensiveness mixing well with Cameron Crowe’s wide-eyed sentimentalism. Still, she’s earned enough accolades as a perennial Next Big Thing to land on the cover of Vanity Fair with other budding hotshots. Playing the part to perfection, she complained when the magazine misidentified the vintage jacket she brought from home as a Tommy Hilfiger.

Given her obvious ambivalence toward being in the spotlight, Polley’s decision to sideline her acting career—and, as far as I can tell, her activism—in favor of working behind the camera is merely a natural progression. Although she may not yet have established a recognizable style, she has certainly settled on a subject: marriage—or, more accurately, commitment and its discontents. All three of her imperfect but occasionally revelatory films dwell on the ruts of monogamy, the allure of the bourgeois cocoon, and the ploys required to manage the most intimate divisions of labor.

* * *

Polley’s directorial debut, Away From Her (2006), tracks a septuagenarian married couple’s attempt to navigate a retirement that has been permanently unsettled by the wife’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis. Although the film met with unanimous accolades (including two Oscar nominations), none of them sufficiently underlined the unlikelihood of an inexperienced twentysomething first-time director making such an elegant, searching film about the inevitable and unexpected heartaches of aging. Though Away From Her provides a relatively faithful adaptation of Alice Munro’s story “The Bear Came Over the Mountain,” it gains much of its power from the curiosity of Polley’s gaze. With calm lucidity, she projects her awe at the story’s central relationship; the movie owes its richness to the fact that it was made by a person much younger than its protagonists, one who can only guess at the magnitude of regret and the magnificence of forgiveness. Rarely moving the camera, Polley bathes the couple in sunlight reflected off snow and suggests that the callow exuberance of youth pales in relation to the thornier emotions of old age. The film is a resolutely unradical debut, yet still smacks of a certain boldness.

The opening shots are a visual corollary to the fluid narrative economy of Munro’s story. The viewer first encounters Grant (Gordon Pinsent) and Fiona (Julie Christie) as they cross-country ski over the level snowscapes near their rural Ontario lake house. In the first shot, the two are side by side; in the second, they proceed in different directions; in the third, they are together again, back on their precarious course. Although they appear to be a portrait of domestic bliss, drinking wine with every meal in a house that Munro describes as “both luxurious and disorderly, with rugs crooked on the floors and cup rings bitten into the table varnish,” the couple’s surface contentment barely conceals a past history of betrayal and recrimination. The details are revealed in muted flashback: Grant, a retired professor, was also a philanderer, and we’re led to believe that whatever rapprochement he and Fiona negotiated was tentative and hard-won.

In part because she trusts her actors and Munro’s words so completely, Polley often turns her attention toward the details of the couple’s home, almost as if she’s wondering what could destroy such cozy serenity; it is important to Away From Her that we witness this disease eating away at the sturdiest possible image of domestic happiness. At the same time, Polley is attuned to the slightest flicker of disorientation even among familiar objects. The film knows that houses are only conditionally and precariously invested with a sense of “home.” Away From Her insists that viewers feel the difference between the couple’s lived-in pocket of contentment and the cheerless, antiseptic drabness of Meadowlake, the assisted-living facility where Fiona—in defiance of her husband’s wishful thinking—opts to move for better medical care. The movie tracks the horror of relocation; as far as Grant is concerned, once his wife has settled into her new environment, she is lost to him.

Devoid of emotional grandstanding, Away From Her could be described as understated, yet the film’s resounding subject is the form of exquisite torture available only to the intimate. Early scenes testify to the private language of mutual respect forged through several decades’ worth of struggle, yet many of Grant and Fiona’s subsequent encounters are subtly barbed, marked by cruel jokes and petty acts of retribution. When Grant tells the story of how they fell in love, he remarks on a mind both “direct and vague, sweet and ironic.” As a result, it’s hard to know how seriously to take Fiona when she insists, staring straight ahead: “I think people are too demanding; they want to be in love every single day. What a liability.” Grant, in turn, is afraid to wonder aloud how much of Fiona’s memory loss, and her subsequent intimacy with a Meadowlake resident (Michael Murphy), is an ironic performance of pent-up spite. And what would it mean for Grant to interpret it as such: just deserts? The film’s flinty gloom suggests that the providing of care is often distinguished by a pragmatic ruthlessness.

If Away From Her arrived in Polley’s hands as a ready-made heartbreaker, it’s much harder to account for the tremendous affective charge of her sophomore effort. The lack of narrative ballast is immediately apparent in the opening minutes of Take This Waltz, the 2012 film Polley directed from her first original screenplay. The introduction of its restless twentysomething protagonist and her impossibly handsome paramour-in-waiting is so contrived, so cloying and so awkwardly staged that I had to keep looking away. A Parks Department copywriter visiting a heritage site in Nova Scotia, Margot (Michelle Williams) is forced by a historical re-enactment squad to pantomime flogging an “adulterer,” and the man with whom she’ll soon commit the sin (and whom she’s never previously met) stands on the sidelines, egging her on. After she stares meaningfully out to sea, taking notes in longhand, she next appears while being pushed toward her airport terminal in a wheelchair. She’s soon tasked with justifying her temporary paralysis to Daniel (Luke Kirby), the man in question, who is conveniently seated in her row on the plane. “I’m afraid of connections…in airports,” she admits, inexplicably nursing a glass of milk. “I don’t like being in between things.” Daniel and Margot exit the Toronto terminal in slow motion to the strains of some saccharine electro-folk, and after a shared cab ride in which they pass the time by blowing a necklace back and forth (really), they realize that they’re neighbors. “I’m married,” Margot finally announces, mercifully puncturing the drippiest meet-cute in movie history.

Somehow, just as the movie threatens to collapse under the weight of its own whimsy, it settles into a more naturalistic mode. For the remainder of Take This Waltz, Margot will waver between the easy intimacy of her apron-clad chef husband, Lou (Seth Rogen, perfectly cast as a subtler, more emotionally resonant version of his usual slacker shlub), and the lusty smolder of the rickshaw driver across the street. The situation is hardly terra incognita, but Polley follows through on her heroine’s decision with such sensitivity and stark honesty that skepticism can hardly gain traction. Rather than getting by on smarts, the movie harnesses the viewer’s investment in a universal predicament and then earns its emotional force through a refusal to trivialize the needs of a single character.

Take This Waltz always seems on the verge of falling apart, seesawing from the inexplicably nutty to the brutally frank. For reasons the screenplay leaves unexplained, Margot and her sister-in-law (comedian Sarah Silverman, playing against type) take a water aerobics class with a group of much older women, and at one point Margot accidentally and very visibly pees in the pool. One scene later, the two women are in the showers, and Polley cuts back and forth from their naked bodies to the wide variety of older, equally naked bodies across the room, noting an unkind set of contrasts and gesturing to her irresolute protagonist that, in matters of the flesh, time is always of the essence.

New Yorker critic Richard Brody called Take This Waltz “vehemently pseudo-Nietzschean” and chided Polley for her putative suggestion that conventionally beautiful bodies belong together. But the film doesn’t endorse Margot’s impulsive decision to jettison her less attractive life mate: the final shot—an exhilarating moment of lyric melancholy set to the Buggles’ disposable ’80s anthem “Video Killed the Radio Star”—leaves Margot in a state of suspended animation, having escaped one comforting vacuum only to find herself in another.

* * *

Because Polley lives in Toronto and had been married and divorced before turning 30, she was forced to field (and deflect) questions about the potentially autobiographical dimensions of Take This Waltz. For her formally tricky and openly autobiographical follow-up, Stories We Tell, she decided to grab the reins harder, self-consciously manipulating the terms of her privacy. She begins the film by setting her father up in a recording booth and situating herself in the control room with an air of impartial remove. What is this, a documentary? Our omniscient overseer prefers the term “interrogation process.”

The movie represents, in part, Polley’s attempt to resolve a series of lingering doubts occasioned by the absence of her mother, Diane, who died of cancer when Polley was 11. A restless and tormented figure, Diane was a celebrated Canadian stage actress and free spirit whose flirtatiousness was so legendary that it even provided eulogy fodder. When Polley was growing up, her siblings would question, jokingly but repeatedly, whether Diane’s husband was Sarah’s real father. What if the rumors were true and Sarah’s beloved father, Michael, was not her biological dad?

Stories We Tell is an experimental, process-oriented movie by a director still experimenting with her process. Refusing to conceal her own presence, Polley enlists her father, her siblings and her mother’s friends to tell their own versions of a narrative that has necessarily been stitched together from memory and hearsay. She films them getting ready for their interviews, and she films herself preparing for the sessions: Polley wants her viewers to see the seams. Though their separate accounts of the story—supplemented by an unusual abundance of degraded Super-8 home-movie footage of Diane, Michael and younger versions of the Polley children—present no major discordance, it soon becomes clear that Polley is less interested in what actually happened than in the possibility that, as one of her siblings puts it, there never was a “what actually happened.” At root, Stories We Tell is a textbook exercise in the inescapable instability of personal truth and the performative aspects of even the closest relationships. The problem with this generally riveting film is that Polley, who has mentioned the influence of Orson Welles’s F for Fake and Lars von Trier’s The Five Obstructions, mistakes her emphasis on an unavoidable subjectivity for a radical reinvention of the documentary form.

Critics have dutifully celebrated the film as a breakthrough, but Stories We Tell is sometimes hampered by its insecurities—its need to underline its originality and deflect potential criticism. “I can’t figure out why I’m exposing us all in this way,” Polley says in a voice-over. “It’s really embarrassing, to be honest.” It’s a coy choice of words, since there’s nothing in the movie that makes her look anything less than deliberate. The revelation that much of the film’s Super-8 footage is the work of a team of performers doesn’t register as a stunt; this skillful sleight of hand encourages the viewer to question—along with the film’s principals—how terms like “real” and “imagined” lose their purchase in any examination of the past. And Polley’s coolly authoritarian air when coaxing out her father’s story—“You see what a vicious director you are,” he says—is revealed as a necessary way of throwing him off guard, not a form of cruelty.

If Stories We Tell is less formally risky than Polley assumes, it might also be more revealing than she intends. In a way, her insistence on the movie’s novelty could be interpreted as the corollary of a child’s insistence that her family is unlike all other families. Polley provides her family with a forum to puzzle over and embellish the details of their personal history, rather than defaulting to the inevitable oversimplifications of the celebrity press. For Polley, though the stories we tell are our dearest form of property, and though they can be comforting and powerful, she has no stake in prioritizing one version of the narrative over another.

And yet, even in a film that flaunts invasions of privacy, there are mysteries kept close to the vest. In the film’s most fascinating moment, one of Polley’s sisters shares the fact that all three daughters divorced their husbands after hearing about their mother’s double life. Here, in miniature, is a strong example of how the stories we tell can profoundly influence our most important decisions. In a wise move—one that goes against the grain of an otherwise meticulously annotated film—Polley lets the moment stand without further elaboration.

In the end, Stories We Tell negotiates a resolution more sweet than bitter, as Polley shifts her view from the unknowable mysteries of the dead to the fact of one family member’s sheer, stubborn presence. The movie is less than profound, but so what? As a director, Polley keeps finding new ways to harness the tension between unruly desire and bourgeois comfort; she knows, better than most, that within every decision to settle down lurks the prospect of a grievous unsettling. The movies she’s made thus far locate their female protagonist at the same critical juncture, with each one taking a different path: the first, the woman who stays; the second, the woman who leaves; and the third, the woman who leaves, thinks better of it and comes back, trailing secrets in her wake.

Akiva GottliebAkiva Gottlieb is a writer in Los Angeles.