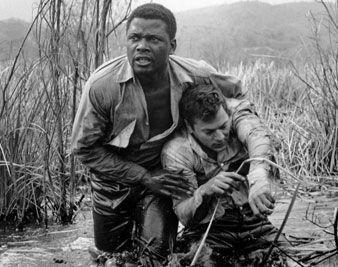

Everett CollectionSidney Poitier and Tony Curtis in The Defiant Ones, 1958.

Everett CollectionSidney Poitier and Tony Curtis in The Defiant Ones, 1958.

Sidney Poitier and Tony Curtis are two inmates in a Southern prison who learn to unshackle themselves from hatred.

Stanley Kramer produces in The Defiant Ones the lowest common denominator of the race problem. His idea is that if you chain a Negro and a white man together and set the dogs upon them, they will learn the advantages of cooperation and may very well end up in an embrace of respect and affection.

A prison truck, transporting convicts on a rainy night, is overturned. One pair of the chained men—played by Tony Curtis and Sidney Poitier—escapes from the wreck, plunges into the sheltering swamp, and begins an agonizing endurance race against the traps of the terrain and the hounds of the posse that is certain to follow. This is the movie chase in pure and elegant form; it is also a handsome apparatus for social symbolism: one man standing on the other’s shoulders; one dragging the other from the maelstrom; one tending the other’s infected wrist (lest he face delirium at the other end of the chain). Similarly, one sees the futility of two men tearing at each other’s flesh when they are shackled to the same future. Toward the end of the picture, the handcuffs are cut off, but by then the Negro and the white are joined by a chain of association and mutual obligation that neither can break. They are, you might say, gloriously united in failure.

I guess that ending is consistent with the characters as described (big lonely boys beneath the toughness), but I would not argue with anyone who held that it was dictated by the goodness of Mr. Kramer’s heart. Mr. Kramer’s heart interferes with the action at several points, and though these lucky accidents are traditional in a chase picture, they do cloud the allegory. The whites and the blacks of the South have been chained together for a good many years, and they have not grown notably sweet toward each other because of the confinement. I can think of several other ways the picture might have worked out—they are a good deal more plausible, though not nearly as pretty.

It is easy to commend Mr. Kramer for the skill with which he uses popular melodrama to elucidate a social problem, but his oversimplification may give people the notion that prejudice is just a big, unhappy misunderstanding and that it can be solved by a little effort at a common goal. Prejudice is a tougher root than that, and sentimentality is a poor weapon in a good cause.

What can be said for The Defiant Ones is that, on its surface, it is first-rate excitement; the acting is strong and simple, the scenery (except for a foolishly phony turpentine camp) is harrowing and well-photographed, the tension builds as it should in one of these nerve-stretching exercises. I wish only that Mr. Kramer would stay clear of the world’s infamy—he has a great love of violence but no stomach at all for evil.