In 2017, the Tennessee state legislature passed a bill designed to expand Internet access in rural areas. At first glance, this might seem have seemed like an amazing display of public service. The challenge that Tennessee and other states face is real: 34 million Americans lack high-speed Internet access, according to a 2016 Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Report. Forty percent of these Americans are in rural areas.

In reality, this was just a dressed-up corporate handout. The bill provided $45 million in subsidies for Comcast and AT&T to provide rural Internet access—and to make matters worse, the companies are only required to offer 10Mbps rates, hardly high-speed service.

But what if the government decided access to the Internet was a basic right, and that profit motives didn’t have to be a central part of the equation? As a new generation of politicians is asking whether it’s time for some new ideas, a public option for Internet access—call it “Internet for All”—might fit the bill. According to our research, it appeals to voters in both the deepest blue and the deepest red districts across the country.

And one Democratic primary candidate hopes it can propel him to the biggest surprise win in a Michigan primary since, well, the last time Michigan had a major Democratic primary.

The lack of access to high-speed Internet service is an underrated and serious problem in America. Not only does a significant part of the country lack such access, many more people don’t have a choice in their provider. Almost 60 percent of neighborhoods (developed census blocks, in the FCC’s technical parlance) have either no high-speed Internet access or only one option. Almost 90 percent of neighborhoods have no access at all to Internet speeds of 100 Mbps. And without competition, monopolies can jack up the prices while cutting back on service.

“Internet for All” could provide both access and competition. The idea is simple: Cities, counties, or states could offer high-speed Internet access in a way similar to how they provide other public utilities, but with the caveat that, unlike electricity or water, Americans would be free to contract with Comcast or whomever else they like if they don’t want to use the public option. “Internet for All” would mean both that everyone in America—rural, urban, and suburban alike—would have access to high-speed Internet service, and that the currently monopolistic Internet providers would have a competitive incentive to cut prices and improve their service, lest people sign up for the public broadband.

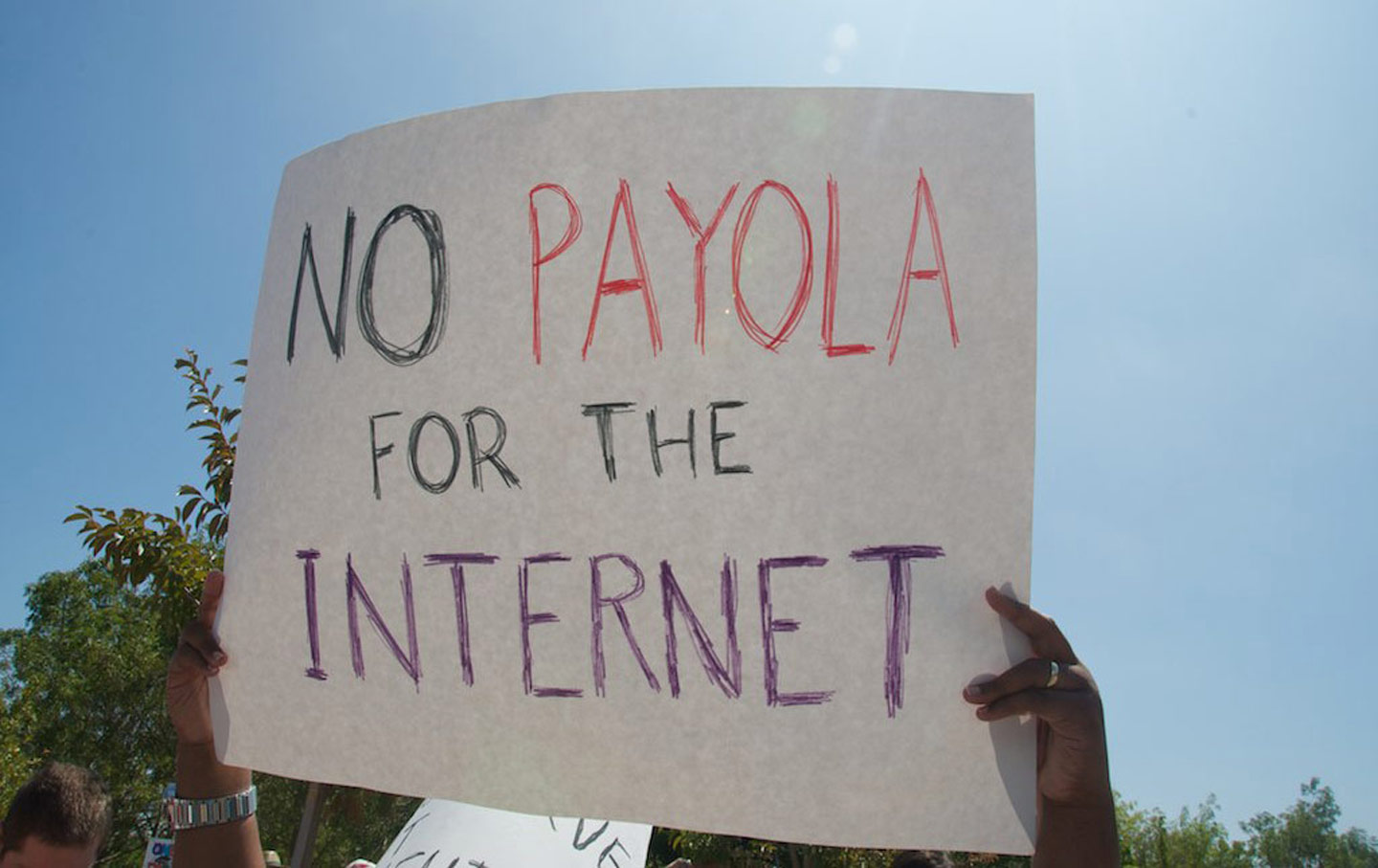

Abdul El-Sayed, a progressive candidate for governor in Michigan, is pitching this idea to voters. “Corporations shouldn’t be able to rule the information superhighway,” he said. “With the repeal of net neutrality and rise of Internet monopolies that charge too much for subpar service or ignore communities altogether, public broadband has to be part of the resistance to their greed. Everyone deserves access to fast, affordable Internet and right now, corporate ISPs aren’t getting the job done on their own.”

Ayanna Pressley, a Democratic candidate in Massachusetts’ Seventh Congressional District, which contains mainly urban areas, has also keyed into the issue. “Disparities in access to affordable, high-speed Internet exacerbate persistent opportunity gaps and can impact our local communities, from small-business owners to elementary-school students,” she said.

The challenge is that for many candidates, new and exciting ideas like “Internet for All” are rarely polled or discussed. “Support for progressive policies is increasing, but we need credible data points to prove to more moderate Democrats that this platform is not a liability,” El-Sayed said. “In fact, it’s the best way to earn back the support of working people.”

We decided to take up this charge. Data for Progress, a think tank that two of us recently founded with data scientist Colin McAuliffe (who contributed data analysis for this article), conducted a nationally representative survey seeking to inform discussions on progressive issues like a public option for the Internet. In general, our results show something that many mainstream publications may find surprising: Many progressive policies are highly popular, and can help Democrats in the places they’ve been struggling the most.

Data for Progress commissioned this poll from YouGov Blue, a widely respected pollster with a strong track record of success in predicting election outcomes. We collected a nationally representative sample of 1,515 adults between July 13 and 16. A deeper dive into the data and full question wordings are available on our website. Because these policies are new, we expected to see some uncertainty and we gave respondents the option of indicating that they didn’t know or didn’t have a strong preference.

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation

Nevertheless, the idea garnered broad support across the political spectrum.

We asked whether eligible voters would “support or oppose the creation of a publicly owned Internet company to fill coverage gaps in rural, urban, or remote areas that currently lack robust Internet access.” Majorities in every state endorsed the policy.

Support for “Internet for All” exists across a variety of relevant groups. Trump voters support the policy—43 percent in favor to 28 opposed. Nonvoters support the policy at a rate of 45 percent in favor to only 13 opposed. Working-class (non-college) whites, the voters Democrats have struggled with in 2016, support the policy 54 percent in support to 15 percent, as do working-class people of color (48 percent in support, 15 percent opposed). A whopping 77 percent of college-educated people of color support the policy.

The policy has strong support across geographic regions, with majorities of voters living in urban, suburban, and rural areas all reporting support for the proposal. Public Internet service is more popular in rural areas than urban or suburban ones—a rarity for progressive policies. The public option for the Internet has net support of 44 percent (56 percent in support, 11 percent opposed) among rural voters, 36 percent net support among suburban voters, and 41 percent net support among urban voters.

Implementing a public option for the Internet isn’t an absurdly daunting challenge, either. The Electric Power Board in Chattanooga started building a fiber-optics network for the city almost a decade ago. It was providing 1 Gbps service to 60,000 homes and 4,500 businesses by 2015, at only $70 per month. Wilson, North Carolina, offers Gigabit Internet access as well as phone and cable service to its residents.

But unfortunately, innovative cities like these often can’t expand their service. Some states have laws that prevent cities from providing Internet access outside their borders, and courts have upheld those bans, stating that federal laws don’t preempt these restrictive state policies. Reforming state and federal law and offering service at the state, county, or municipal level are practical, workable ideas. Our data provide no reason to believe that Internet for All will be anything other than a political winner for progressive candidates in every part of the country. It should be part of the emerging progressive agenda.

Sean McElweeTwitterSean McElwee is a researcher and writer based in New York City, and co-founder of Data for Progress. Follow him on Twitter @SeanMcElwee.

Ganesh SitaramanGanesh Sitaraman is a professor of law at Vanderbilt Law School.

Jon GreenJon Green is a PhD student at Ohio State University and a co-founder of Data for Progress.