If Democrats mainly rely on wooing moderate Republicans this fall, they will likely lose the opportunity to take back control of the House of Representatives. There simply aren’t enough Republican swing voters out there for Democratic candidates to amass the number of votes necessary to prevail in November’s midterm elections. And if Democratic institutions and organizations insist on prioritizing such a path, they will waste tens if not hundreds of millions of dollars and fail to fulfill their mission of stopping the wave of white supremacy, racism, and widespread hatred that is washing over this country.

Much of Democratic strategy, and a shockingly high amount of campaign spending in midterm elections, is based on a popular—but false—narrative about US voters. The narrative holds that the electorate consists of large numbers of “swing” voters whose allegiances shift back and forth depending on how they feel things are going in the country and who is addressing their concerns. David Axelrod’s take on the 2010 midterm elections bought into this trope. In his book Believer, he asserted that by signing health-care reform into law in 2010, “[Obama’s] standing with moderate, swing voters had taken a hit…. he had ignited a blazing grassroots opposition that would cost him his House majority.”

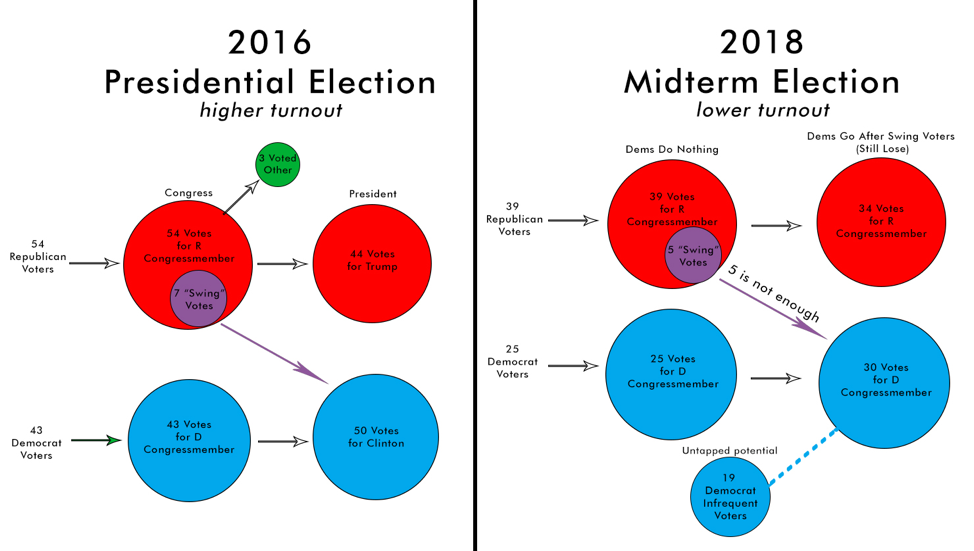

But that’s not how the House was lost in 2010. It wasn’t that the huge hordes of swing voters recoiled against the legislative overreach of our nation’s first black president. It was that too many of the hordes of voters who’d propelled a black man into the White House in 2008 sat out the 2010 elections. Conversely, those who hated Obama, and everything he stood for, came right back out and voted in large numbers in 2010, so when paired with the absence of many solid Democratic votes, the GOP was able to retake control of the House. I’ve shared this before, but this chart from my book, Brown Is the New White, can’t be shown often enough:

This year, Democrats need to pick up 23 seats in the House, and there is a lot of emphasis (including from me) on the 23 Republican-held districts where Hillary Clinton beat Trump. While we can take some solace from the fact that the majority of voters in those districts did not cast their ballots for Trump, they still bestowed their favor on the incumbent Republican representative in their districts, often by large margins.

This is where the critical strategy and spending implications come into play. Political investments—whether of money or time—should be informed by a sound, data-driven plan, and too much of the current spending is predicated on a superficial, almost wishful, understanding of elections.

Democratic leaders have gone to great lengths, for example, to encourage military veterans to run for Congress this year. Veterans can be great progressive leaders (my father and uncle served in the military, and I was born on a military base), but if the strategic objective is to appeal to swing voters drawn to Trump’s posture and positions, the math doesn’t add up. The painful truth is that there just aren’t that many swing voters.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Doing a deep data dive on the districts reveals that the number of swing voters is far smaller than many people realize, especially when you factor in the drop-off in voter turnout in midterm elections. In the most competitive Republican-held congressional districts, Clinton won by an average of 17,000 votes, but the incumbent GOP congressperson beat his or her Democratic foe by an average of 34,000 votes.

This reality is particularly problematic when you factor in the smaller electorate during midterms, when fewer turn out to vote than in a presidential year. This diagram shows the total voter pool in an average competitive district, how many people voted, and how many voted for Clinton, Trump, and the Republican member of the House. For illustration purposes, if 100 people voted in one of these Clinton-Republican representative-won districts in 2016, the incumbent House Republican received 54 votes, and his or her Democratic opponent received 43 votes. Of those 54 people who voted for the incumbent Republican, seven (out of 100 votes) voted for Clinton. That’s seven moderate Republicans out of 100 voters. Historically, in midterm elections, Republicans are more likely to come back out and vote than are Democrats, and as a result, that 54-43 Republican advantage from the higher-turnout presidential year will be about 39-25 this midterm year (based on historical turnout data). This means Democrats need to find 15 votes in every 100 in order to flip those 23 seats. Looking at the possible sources of an additional 15 percent highlights how few moderate Republicans there are.

If, on average, just seven Republicans are moderates, and Democrats need 15 additional votes, Democrats will obviously fall short. Where else then could and should Democrats look? The more promising pools of people are actually Democratic voters—many of whom face greater economic obstacles in finding the time and transportation to get to the polls.

In the quest for those necessary 15 votes, the number-one place Democrats should look is among the 19 percent of Democrats who voted in 2016, but are unlikely to cast ballots this year.

In races that may well be decided by a few thousand votes (for example, Pennsylvania Democrat Conor Lamb won his special US House election earlier this year by a mere 627 votes), it makes sense to also target the 20,000 young people in each congressional district who were not old enough to vote in 2016, but are now eligible.

In fact, the largest pool of people Democrats should be trying to tap is actually nonvoters—the 200,000 people per district who were eligible but didn’t cast ballots in 2016. It is in these sectors of society where Democrats will find the source of success and the path to winning back the House… and taking back our country… and winning elections for years to come.

It is hard work to get all of these voters out, but that is the work that will determine success or failure this fall.