Candidates for DNC chair meet in Detroit on January 16, 2025.

(Politico / YouTube)Democrats are reeling from the defeats they suffered in last November’s election. On Saturday, they have their first big chance to determine how to bring themselves back from the political wilderness—by selecting a new slate of leaders for the Democratic National Committee.

The party has credible candidates for the post of DNC chair, and for the various vice chair and executive positions that will be filled by the 448 party insiders, labor leaders, and elected officials who will make the call.

Much of the media has been focused on the contest for chair because of the prospect that the winner could emerge as a leading face of opposition to the dangerous presidency of Donald Trump. That’s especially true, argue activists with groups such as MoveOn and the Progressive Change Campaign Committee, if it is a dynamic figure such as Democratic Party of Wisconsin chair Ben Wikler, one of two front-runners in the race for the top job, the other being Minnesota party chair Ken Martin, a veteran organizer who was mentored by progressive former US senator Paul Wellstone.

Certainly, pushing back against Trump will be a vital task for the new top team. But that’s not enough. Democrats need leaders who will drive a radical transformation of their party’s character and vision. After all, this is a political organization that, despite its considerable resources and hard-working candidates, could not muster enough support in 2024 from its traditional base of working-class voters to defeat Republicans with positions so irrationally plutocratic that they would, just a few years ago, have been on the far fringe of American politics.

The overhaul must be both internal and external.

What’s needed is a Democratic Party where grassroots activists and their allies in labor, environmental, and civil rights organizations sweep the pablum of past messaging aside and replace it with an absolute commitment to economic and social and racial justice that gives frustrated Americans something to vote for.

That means that the next DNC chair cannot be simply a competent manager—or, worse yet, a mere fund-raising complement to the party’s plodding congressional leadership. The chair, along with the vice chairs, must lead in a way that ensures that Trump and his minions aren’t the only ones defining our political moment.

History tells us what is required. The party has had transformational chairs in the past: Paul Butler, who was known for “his acidly articulate speeches against the Democratic leaders of Congress, southern segregationists” in the 1950s; Ron Brown, who made a real commitment to diversity and new-voter mobilization (with the help of the Rev. Jesse Jackson) in the late 1980s and early 1990s; and Howard Dean, who introduced the 50-state strategy with considerable success in the 2000s. But what the party needs just now is a new Fred Harris—a 21st-century version of the fierce Oklahoma populist who shook up the DNC during his brief tenure in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

They don’t make politicians like Harris anymore. But today’s DNC members should be looking for a leader who can approximate his combination of internal and external populism.

Harris, the senator from Oklahoma who famously sought the Democratic presidential nomination in 1976 with the slogan “Tax the Rich!”—and the campaign promise of “No More Bullshit!”—died last fall at age 94. Most of the obituaries remembered him as a committed anti-racist (he was the last surviving member of the Kerner Commission, which identified “pervasive discrimination and segregation” as an explanation for the riots that swept American cities in the 1960s), the one senator who had the wherewith all to vote against the Supreme Court nomination of Lewis (“Powell Memorandum”) Powell, and the champion of a progressive populism that anticipated the anti-corporate, pro-worker, take-down-the-oligarchs politics of the Rev. Jesse Jackson Jr., Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, and New York Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

But Harris also had a brief rip-it-up-and-start-again tenure as chair of the Democratic National Committee.

His time in charge was too short—less than a year and a half in 1969 and 1970. While Harris put the pieces in place to empower grassroots Democrats, he was not given the time to complete the work of making the Democrats into the sort of multiracial, multiethnic, 50-state movement for economic justice that he envisioned.

Now, more than 50 years after Harris’s time as DNC chair, Democrats need to finish the work he started if there is to be any hope for the party’s future.

When Harris was named DNC chair in January of 1969, a Time magazine report on the selection was headlined, “Nowhere to Go But Up.” The party was in dire straits following the 1968 election. Four years after Lyndon Baines Johnson had won the 1964 presidential election with an epic 61–39 popular vote win that swept Democrats into office nationwide, Johnson’s vice president, Hubert Humphrey, won just 42.7 percent of the vote in a race that he lost to Republican Richard Nixon.

After a Democratic National Convention that saw violence on the streets of Chicago and chaos within the hall, the Democratic coalition fell apart, with Northern liberals backing Humphrey as Southern segregationists and many Northern working-class voters backed the race-baiting third-party bid of Alabama Governor George Wallace. It was so bad that Time wrote that, for Democrats, “the consoling advantage of falling so low, as drunks and defeated politicians both know, is that there is nowhere further to fall.”

Harris, then a 38-year-old-year firebrand whom Humphrey had considered for a vice-presidential running-mate, was put in charge of cleaning up the mess. But the senator’s vision was more ambitious than that.

He wanted to remake the Democratic Party as a movement organization with the mission of fighting poverty in America. Harris promised, “We’ll make the party so vigorous on issues, that the people we need will want to get involved.”

To accomplish his goals, Harris fought to make sure that the party welcomed newcomers. Recalling the 1968 convention, he said, “The Democratic Party was not democratic, and many of the delegations were pretty much boss-controlled or -dominated. And in the South, there was terrible discrimination against African-Americans.”

Harris worked to knock down barriers to participation by women, people of color and the young anti–Vietnam War activists who had backed the 1968 campaigns of Eugene McCarthy and Bobby Kennedy. He created a commission that successfully reformed the delegate selection process for future national conventions—seeking to replace bosses and backroom deals with something akin to democracy.

There was pushback in Harris’s time, just as there is pushback today. But the Oklahoman knew that the Democratic Party needed to change.

Harris wanted to identify the Democrats as the vehicle for raising people of all races out of poverty and to make the party the political wing of the working class. While he served as DNC chair, Harris was still a senator. When Nixon proposed welfare reforms that would guarantee a minimum annual income of $1,600 for a family of four, Harris pushed back, saying, “A floor at such a low level. Instead of raising families out of poverty, would mean for many a sad plunge into the lower depths of ever greater poverty.”

The Oklahoman’s alternative was a bold plan to provide economic security for all Americans. He advocated for stronger unions, higher wages and government interventions that would assure that no family would fall below the 1970 poverty line of roughly $3,900.

That was a radical vision for fundamental change—not just of the Democratic Party but of the country. Pushed by Harris and his allies at various stages in the early 1970s, many in the party entertained a move toward the sort of progressive populism that would later be exemplified by Harris aide Jim Hightower. Unfortunately, the work of making the party the clear-eyed, unequivocal advocate for the working class that was needed to overcome the divisions of that era was never completed.

Decades later, Hightower and many others argue that this approach is still viral to overcome the divisions of the current era. Since the 2024 election, their argument has gained traction, and has become a focus of the race for party chair.

When he was DNC chair and later as a presidential candidate, Fred Harris sought to create a Democratic Party that was recognized for its opposition to privilege.

“The fundamental problem is that too few people have all the money and power, and everybody else has too little of either,” he argued. “The widespread diffusion of economic and political power ought to be the express goal—the stated goal—of government.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →And of a Democratic Party that, along with new leadership, needs a fresh commitment to fighting as a multiracial, multiethnic, multigenerational, multiregional alternative to the politics of privilege that has empowered Donald Trump and Elon Musk.

More from The Nation

Symbolic Legislation Will Not Get Us Free Symbolic Legislation Will Not Get Us Free

If the Democrats are truly serious about protecting reproductive freedom, they must rise above reactive politics.

Senate Democrats Are Attacking Tulsi Gabbard for the Wrong Reasons Senate Democrats Are Attacking Tulsi Gabbard for the Wrong Reasons

Preferring to defend spy agencies and line up behind the hawkish consensus, the bipartisan elite ignores the director of national intelligence nominee’s rampant Islamophobia.

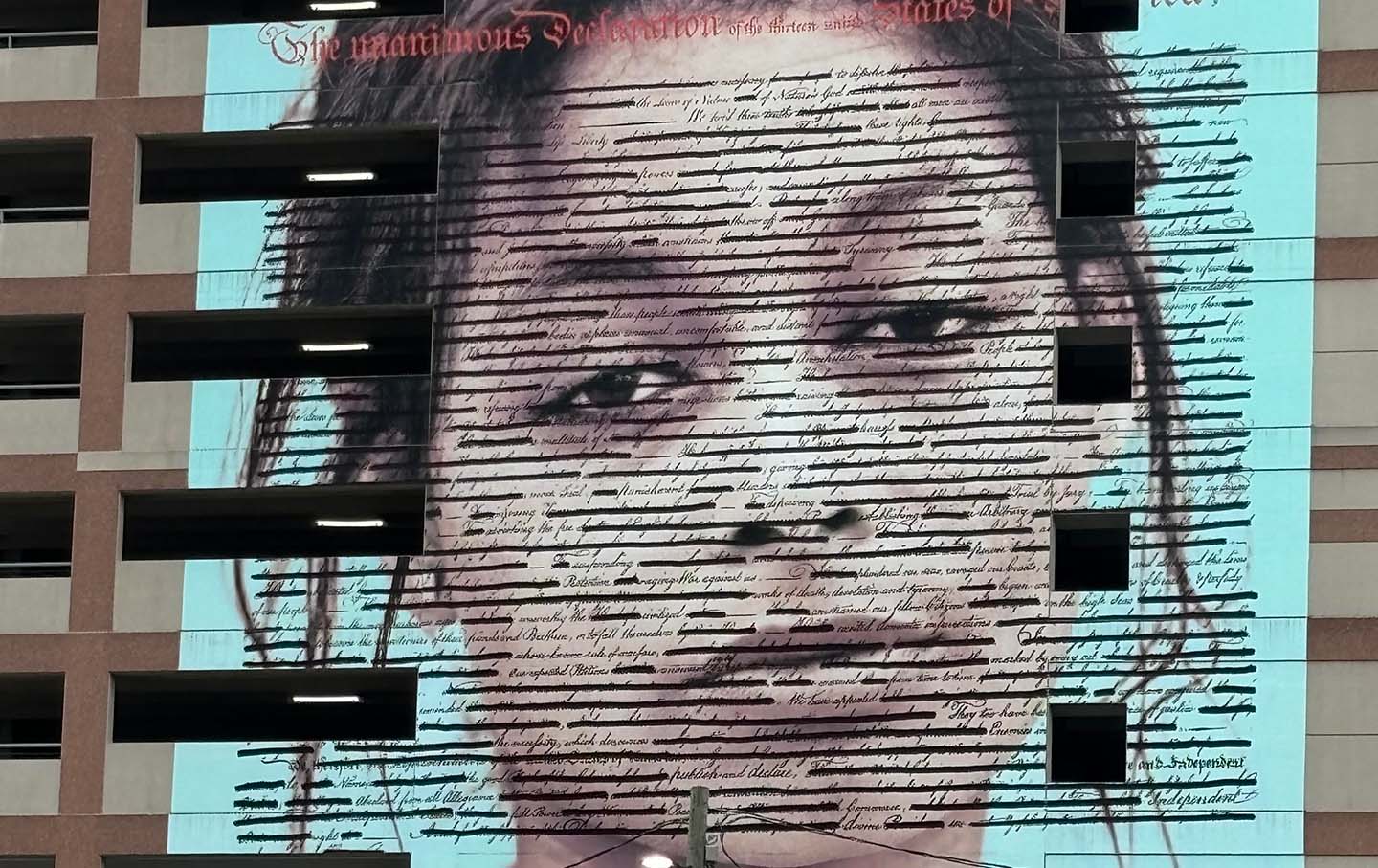

Declaration: Who Gets Redacted ? Declaration: Who Gets Redacted ?

A revolutionary document and evidence of many contradictions in the history of the United States.

Ken Martin Wants Democrats to “Win the Wellstone Way” Ken Martin Wants Democrats to “Win the Wellstone Way”

Inspired by the late senator from Minnesota, the DNC chair candidate wants to build a working-class party that organizes diverse urban-rural coalitions.

Don’t Be Fooled: The Funding Freeze Drama Is Not Over Don’t Be Fooled: The Funding Freeze Drama Is Not Over

While the White House claimed to have rescinded the memo implementing the order, it then made clear that the order itself—and possibly the freeze—are still in place.