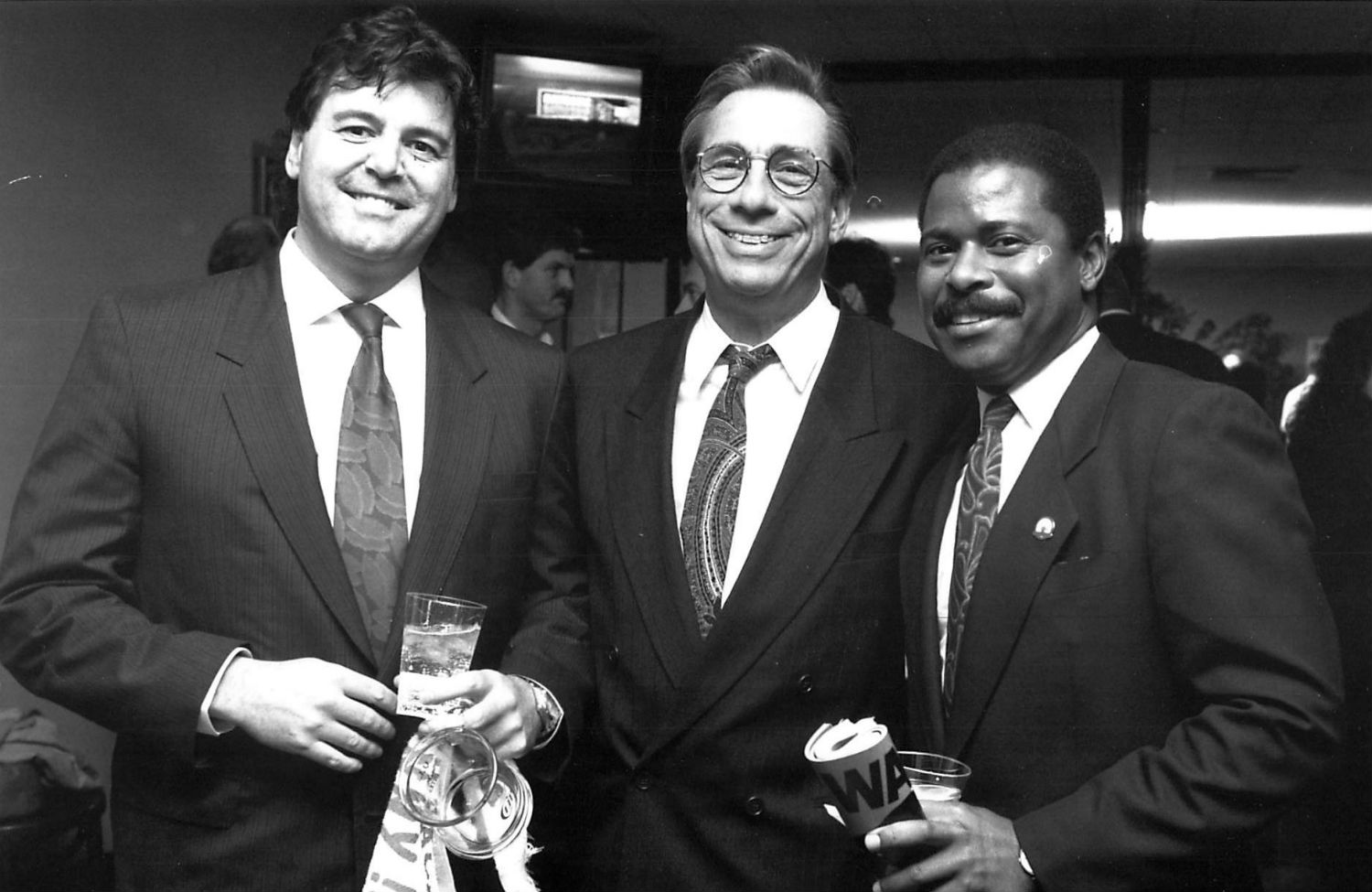

Los Angeles Clippers owner Donald Sterling (center), at an NBA event in 1989. (Courtesy of Cliffwildes, CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Following the uproar over audio revelations of a racist rant by Los Angeles Clippers owner Donald Sterling, it is worth noting that Sterling’s racism is nothing new and should come as no surprise. Reprinted—with some edits—here is the essay on Sterling that I wrote for my 2010 book Bad Sports: How Owners Are Ruining the Games We Love. It is out of date insofar as the Clippers have gone from being a sad-sack franchise to contending for the 2014 NBA title, but everything else holds. Hopefully it will give some insight into a man who has become, in the words of Magic Johnson, “a black eye for the NBA.”

It takes a certain flair for racism—a panache for prejudice—to find yourself facing two different racial discrimination lawsuits simultaneously. Meet Donald Sterling, the owner of the most unspeakably malodorous franchise since the Cleveland Spiders: the Los Angeles Clippers. Since Sterling’s purchase of the club in 1981, his team has by far the worst record in all of the National Basketball Association. The Clippers have made the playoffs only four times in Sterling’s twenty-eight years as owner, never advancing past the second round of the playoffs. It’s been said that the NBA should rename its annual players draft “The Donald Sterling Draft Lottery.” He was named the worst owner in sports by the writers at ESPN.com because of his complete disregard for fielding a winning team as long as he could turn a healthy profit. It stands to reason why in 2000 Sports Illustrated named the Clippers “the worst franchise in professional sports.”

But Sterling transcends the stereotypical Scrooge-like miser. He is so much more boorishly colorful than just a man trying to fill his coffers while snoozing in the luxury box. Sterling is like a side character in a James Ellroy noir novel. He is ruthless and toothsome, a man who unabashedly reinvented himself in Los Angeles’s healing sunshine. Former LA Mayor Tom Bradley once said, “People cut themselves off from their ties of the old life when they come to Los Angeles. They are looking for a place where they can be free, where they can do things they couldn’t do anywhere else.”

That well sums up the tale of Donald Sterling. His real name is Donald Tokowitz. After moving from Chicago as a child, he came of age in the rough and tumble Boyle Heights area of Los Angeles. Donnie Tokowitz was the only son of an immigrant produce peddler. As a young boy, he worked boxing groceries at the local grocery stores and showed a talent for saving money. “As a kid, Donald never had enough of anything,” said a friend. “With him, acquiring great wealth is a crusade. He’s psychologically predisposed to hoarding.” His mother was not impressed with his ability to hustle a dollar and insisted that he go to college and become a lawyer. Young Mr. Tokowitz worked his way through Southwestern School of Law, graduating at age 23. To help pay his way through, he worked nights selling furniture. It was there that he changed his name to Sterling. “I asked him why,” a coworker told Los Angeles magazine. “He said, ‘You have to name yourself after something that’s really good, that people have confidence in. People want to know that you’re the best.’”

After some success as an attorney he started buying property throughout Los Angeles, and kept buying and flipping real estate until he earned enough to buy the then San Diego Clippers for $13 million, $10 million of that on layaway. By ownership standards, he was practically proletarian.

Before fleeing to Los Angeles, he ended any prospect of professional basketball in San Diego by being the most personally repellent owner in the game. In San Diego, he was like Mark Cuban, if Cuban maintained his outsized personality while actively trying to destroy his team. “It’s the start of a new era!” he promised in an open letter to fans. “I’m in San Diego to stay and committed to making the city proud of the Clippers. I’ll build the Clippers through the draft, free agency, trades, spending whatever it takes to make a winner.”

They were gone within five years.

As Sports Illustrated wrote in 1982, “Sterling is a good example of the kind of ownership problems the league has had in recent years.… He started his crusade with a campaign to boost ticket sales that, oddly enough, featured Sterling’s grinning face on billboards throughout San Diego County.” They won their opening game of that 1982 season, and Sterling skipped around the court after the 125-110 victory. Then, his shirt unbuttoned down to his waist, he gave coach Paul Silas a big smooch. This behavior would be charming if, that same first season, he wasn’t accused of stiffing players on their paychecks.

It didn’t help that his assistant general manager was named Patricia Simmons, an ex-model who had what one San Diego newspaper described as “no known basketball background.” When Silas was in China on a Players Association exhibition tour this summer, Simmons moved into his office. When Silas returned, he found his belongings stacked in the hallway.

This kind of bizarre behavior is why in 1984 Rothenberg, then the team president, predicted about Sterling, “You’re going to call him the Howard Hughes of the NBA.”

The San Diego Clippers were an embarrassment, averaging fewer than 4,500 fans per game for three consecutive seasons. Sterling could have tried to stick it out, but instead he packed up and urged on by his friend Los Angeles Lakers owner Jerry Buss, moved the team, now derisively called the Paper Clips, to LA in 1984. Sterling undertook the move without first receiving approval from the league, which fined him $25 million. Sterling countersued for $100 million but withdrew when the new commissioner David Stern dropped the fine to $6 million.

While Sterling has cobbled together a terrible franchise, he is seen as a visionary at the art of turning his team into a cash cow, dumping contracts, pocketing television revenue and collecting his share of the NBA’s luxury tax. The cheapness of Sterling is the stuff of myth, if not legend. During his first season as owner, he asked coach Silas if he could double as the team trainer and take up the duties of taping players before games. During the 1998–99 NBA owners lockout, when almost half the season was cancelled, Sterling chose simply to not hire a coach for six months. (The Clippers finished the lockout season with a sterling 9-41 mark.) Not one of Sterling’s nine lottery picks before 1998 re-signed with the team.

“Being a Clipper can be real tough,” said retired point guard Pooh Richardson, who played for the Clippers from 1994–99. “It’s almost a given that you won’t win and that the team won’t hold on to its best players.”

“At some level Sterling must be content being the losingest NBA owner ever,” said super-agent David Falk. “All the criticism he has gotten hasn’t changed the way he runs the team one degree.”

Sterling says he hates to lose. He said plaintively to a reporter, “Basketball is the only aspect of my life in which I haven’t been a winner. I want to win badly, I really do. It hasn’t happened yet, but it will. Don’t you think it will?… It must. It simply must.”

But if Sterling really wants to win, he loves being an owner even more. He’s never come close to winning a championship and compensates by holding NBA lottery parties at his Beverly Hills estate. As Sports Illustrated reported,

Sterling has often prepped for his parties by placing newspaper ads for “hostesses” interested in meeting “celebrities and sports stars.” Prospective hostesses have been interviewed in the owner’s office suite. One former Clippers coach recalled dropping in on Sterling during a cattle call. “The whole floor reeked of perfume,” he said. “There were about 50 women all dolled up and waiting outside Donald’s office, and another 50 waiting outside the building.” The chosen get to mingle with D-list celebrities and drink wine from plastic cups.

Sterling has even been penurious enough to share an arena with the Los Angeles Lakers. It certainly makes business sense. Since leaving the LA Sports Arena and sharing the Staples Center, Sterling has opened up his wallet for players like Elton Brand and Baron Davis (both signings, disasters). But the comparison between the two clubs is rather consistently unkind.

The Lakers have been to twenty-six NBA Finals and won twelve championships. The Clippers have the most sixty-loss seasons in NBA history. It’s the prince and the pauper sharing space at the Staples Center. As comedian Nick Bakay wrote, “The Lakers’ luxury box is prawns, caviar and opera glasses[,] while the Clippers stock Zantac, barf bags, some good books, and cyanide.”

Sterling dismissed the comparison, saying, “Let’s say you take your child to see Shirley Temple onstage. And let’s say you tell yourself, ‘Wouldn’t it be nice if that was my child up there?’ And you think, ‘My child will never be Shirley Temple, but I love her all the same.’ So you send her for dancing and singing lessons and hope that one day she’ll have all the qualities you admire in Shirley Temple. But she’ll never be Shirley Temple.” It’s lines like this which led him to be described as a having “the furtive, feral charm of an old-time movie mogul.”

You might be tempted to think that playing for Sterling would at least be interesting. The man is a character, not a suit. But he is also a notoriously cheap and verbally abusive bigot. Sterling stormed into the team’s locker room in February 2009 and unleashed what was described as a “profanity-laced tirade” at his players, calling young player Al Thornton “the most selfish basketball player I’ve ever seen.” When Thornton looked beseechingly to his coach Mike Dunleavy, Sterling told Dunleavy to “shut up.” He also, according to his former GM Elgin Baylor, “would bring women into the locker room after games, while the players were showering, and make comments such as, ‘Look at those beautiful black bodies.’ I brought [player complaints] to Sterling’s attention, but he continued to bring women into the locker room.”

Clipperland is a place where any player with potential is either not re-signed or desperately tries to leave before their potential is squandered. In 1981 they picked Tom Chambers with the number-eight pick, and then in 1982, they nabbed Terry Cummings (who won Rookie of the Year) number two overall. The two appeared in six combined All-Star Games and 228 combined playoff games—of course, none with the Clippers. Both got the hell out of Dodge by the summer of ’84.

If only that were the full extent of Sterling’s sins.

Sterling is narcissistic and CliffsNotes literate enough to present himself as a self-made Gatsbian figure. He even has “white parties” at his Bevery Hills home where guests all wear white “like in the book.” He’s a Gatsbian who never read The Great Gatsby. Jay Gatsby was running from his past, hiding his rough background behind the artifice of taste and wealth. Sterling presents himself as the tony developer of high-end properties in the Hollywood Hills, and plays it much closer to the street. Sterling is also the Slumlord Billionaire, a man who made his fortune by building low-income housing, and then, according to a Justice Department lawsuit, developing his own racial quota system to decide who gets the privilege of renting his properties. In November of 2009, Sterling settled the suit with the US Department of Justice for $2.73 million, the largest ever obtained by the government in a discrimination case involving apartment rentals. Reading the content of the suit makes you want to shower with steel wool. Sterling just said no to rent to non-Koreans in Koreatown and just said hell-no to African-Americans looking for property in plush Beverly Hills. Sterling, who has a Blagojevichian flair for the language, says he did not like to rent to “Hispanics” because “Hispanics smoke, drink and just hang around the building.” He also stated that “black tenants smell and attract vermin.”

The Slumlord Billionaire has a healthy legal paper trail, which creates a collage of someone very good at extorting rents from the very poor. In 1986, the spiking of rents in his Beverly Hills properties—the so-called “slums of Beverly Hills”—led to a large march by tenants on City Hall.

In 2001, Sterling was sued successfully by the City of Santa Monica on charges that he harassed and threatened to evict eight tenants living in three rent-controlled buildings. Their unholy offense that drew his ire was having potted plants on balconies. Talk about “hands on.” How many billionaires drive around their low-income housing properties to look for violations? That’s Donnie Tokowitz in action. Two years later, Sterling was effectively able to evict a tenant for allegedly tearing down notices in the building’s elevator.

In 2004, Sterling led a brigade of other landlords to smash Santa Monica’s ultra-strict Tenant Harassment Ordinance. The ordinance stated that issuing repeated eviction threats to tenants was a form of harassment. Sterling and his crew believed that they should be allowed to harass to their hearts content. There are only so many potted pants a man can stand!

That same year, an elderly widow named Elisheba Sabi, sued Sterling for refusing her Section 8 voucher to rent an apartment. Sterling emerged crowing and victorious. (That had to feel good. Damn elderly widows.)

And in 2005, Sterling settled a housing-discrimination lawsuit filed by the Housing Rights Center, which represented more than a dozen of his tenants. He paid nearly $5 million in legal fees for the plaintiffs—a staggering amount—along with a reportedly massive, albeit confidential, sum. Not all the plaintiffs, though, lived to see their windfall. Court documents state that on July 12, 2002, “Kandynce Jones was under threat of eviction by [Sterling] even though she had never missed a rent payment. Ms. Jones, who is a senior citizen and a person with a disability, suffered a stroke caused by the stress [of Sterling’s] housing practices. On July 21, 2003, Ms. Jones passed away as a result of that stroke.”

Amidst all that was described above, there are a web of lawsuits and complaints leveled against Sterling that suggest he is willing to suffer endless financial penalty and legal embarrassment if it means he can have control—always control—over who gets to live in his property.

As sports columnist Bomani Jones wrote, “Though Sterling has no problem paying black people millions of dollars to play basketball, the feds allege that he refused to rent apartments in Beverly Hills and Koreatown to black people and people with children. Talk about strange. A man notoriously concerned with profit maximization refuses to take money from those willing to shell it out to live in the most overrated, overpriced neighborhood in Southern California? That same man, who gives black men tens of millions of dollars every year, refuses to take a few thousand a month from folks who would like to crash in one of his buildings for a while? You gotta love racism, the only force in the world powerful enough to interfere with money-making. Sterling may have been a joke, but nothing about this is funny. In fact, it’s frightening and disturbing that classic racism like this might still be in play.”

Former NBA commissioner David Stern, always so PR-conscious when it comes to where players mingle, how players dress, whom players consort with after hours, has turned a blind eye to this disturbing pattern. Now these chickens have returned to Stern’s back porch to roost. There is a second racism lawsuit buzzing around Sterling’s helmet of hair.

Sterling’s other lawsuit comes from inside his own NBA offices: his long-time general manager Elgin Baylor. Baylor, an NBA legend with the Los Angeles Lakers, has spent more than two decades making a series of personnel decisions that have ranged from depressing to enraging. Baylor’s was called without irony by a television commentator as “veteran of the lottery process” watching the ping-pong balls bounce around to see who gets the number-one pick. The Clippers draft picks under Baylor’s tenure—and their entire roster—have largely been a dyspeptic horror show. According to Baylor, one reason for their continued ineptitude was Sterling in telling Baylor he wanted to fill his team with “poor black boys from the South and a white head coach.”

A Clippers draft pick who could actually play was Kansas star Danny Manning. Manning didn’t last in LA. This might be because Sterling, according to Baylor, would grumble that he didn’t like being in a position where “I’m offering a lot of money for a poor black kid.” Baylor’s lawsuit claims the team has “egregious salary disparities” based on race. Baylor claims he was told to “induce African-American players to join the Clippers, despite the Clippers’ reputation of being unwilling to fairly treat and compensate African-American players.” Baylor says the owner, Donald Sterling, has a “pervasive and ongoing racist attitude.” It also stated that Sterling made clear to Baylor that hiring an African-American head coach was not his preference. This is why Baylor’s lawyers accuse Sterling of having a “vision of a Southern plantation–type structure.”

This news is hardly the public relations boost that NBA commish David Stern relishes. And it’s not the first time Sterling has put his foul foot forward. Sterling had to testify in open court that he regularly paid a Beverly Hills hooker for sex, describing her as a “$500-a-trick freak” with whom he coupled “all over my building, in my bathroom, upstairs, in the corner, in the elevator.” Stern, as one commentator noted, “normally has to explain away the behavior of 20-something athletes, not married 70-year-old club owners worth nearly a billion.”

I guess a billion buys a lot of Viagara. Sterling went on to give the woman in question credit for “sucking me all night long” and whose “best sex was better than words could express.” I will now scream into a pillow while performing a home-lobotomy. The very bombastic, very married Sterling testified that he was “quietly concealing it from the world.” Sterling had a blunt appraisal of his “exciting” relationship with the woman in question: “It was purely sex for money, money for sex, sex for money, money for sex.”

In an even greater leap to the absurd, the lawsuit was not initiated by the vice squad or any controlling legal authority. It was initiated by Sterling against his “$500-a-night trick” because he just couldn’t bear the thought that she was occupying a home she claimed he gifted to her. He was done with her and wanted her out. He also seems to have wanted to proclaim to the world, that at 70, Donald Tokowitz could still throw it down in the sack. If Sterling wants to be a geriatric Charlie Sheen, that’s his business. But in a sport that polices the character of its players, from their dress code to where they spend their leisure time, to what they say to the press, it seems the height of hypocrisy that Sterling skates.

Sterling and the Homeless

For someone whose hobby is unjust evictions, Sterling’s charitable pet project is helping the homeless. Sterling’s homeless “activism” consisted of him buying an $8 million warehouse with big plans to turn it into the $50 million Donald Sterling homeless center. We know of Sterling’s plans not from any press conference with homeless rights activists, or a ribbon-cutting ceremony or even efforts to secure permits from the city. We are aware of his unparalleled generosity because Sterling bought a series of full page ads in the front section of the Los Angeles Times to tell us how generous he is. The ads do more than trumpet Sterling. They seem designed by him as well, or by a man who would unbutton his shirt to the waist in public.

Each ad contains Donald Sterling’s massive head, complete with a smile showing a mouth of capped teeth (or maybe white Chiclets), hair by Blago and skin stretched tighter than a Sunset Boulevard miniskirt. Underneath Sterling’s head it reads, “Please don’t forget the children, they need our help.”

Sterling has taken out full-page ads before, often times ones that proclaim him the recent recipient of some “humanitarian of the year” honor. But the shelter ads were worse because they raised the hopes of an entire community in LA starved for funds and relief. As Patrick Range McDonald wrote in the LA Weekly, “The advertisements promise a ‘state-of-the-art $50 million’ building on Sixth and Wall streets, whose stated ‘objective’ is to ‘educate, rehabilitate, provide medical care and a courtroom for existing homeless.’… These days, though, Sterling’s vow to help the homeless is looking more like a troubling, ego-inflating gimmick dreamed up by a very rich man with a peculiar public-relations sense.… From homeless-services operators to local politicians, no one has received specifics for the proposed Sterling Homeless Center. They aren’t the least bit convinced that the project exists.’”

Tom Gilmore, who served for six years on the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority said, “I’m generally a very optimistic person, but this thing smells like shit. The Los Angeles Times ads aren’t cheap. He could’ve stopped buying the ads and spent that money on homeless people.” Gilmore, who’s been working downtown since 1992, adds, “I’ve never seen [Sterling] down here in my life.”

Reverend Alice Callaghan, who works with the 4,000 people on LA’s skid row at any given time, was even more blunt: “It’s the lowest of the low if he’s using the homeless to make himself look good,” she said. “Or it’s the dumbest of the dumb. No one builds those kinds of shelters down here anymore. He’s a businessman. He can make anything happen. So if it’s not happening, there’s a reason for it.”

When we consider the terrible budget deficits and constant crisis the state of California finds itself mired in—and when we couple that with the walking train wreck that is Donald Sterling—perhaps the Clippers should become the first NBA team to be fan-owned like the Green Bay Packers. Then they could be a team that can truly help the homeless and give something back to the neediest residents of Los Angeles… and Donald Sterling and his “plantation mentality” could finally be gone, an owner no more.

Dave ZirinDave Zirin is the sports editor at The Nation. He is the author of 11 books on the politics of sports. He is also the coproducer and writer of the new documentary Behind the Shield: The Power and Politics of the NFL.