“When the Ferus Gallery began exposing the rest of the country to Los Angeles art in the fifties, New York art people quickly observed that everyone seemed to be obsessed with perfection in L.A.,” writes Eve Babitz in an early chapter of Slow Days, Fast Company, her lightly fictionalized chronicle of 1960s and ’70s Los Angeles. “The frames had to be perfect—the backs of the frames, even.”

If any artist of that era can be said to have been obsessed with perfection, it would be Vija Celmins, the Latvian-born painter who is currently the subject of a sprawling and enchanting retrospective, “To Fix the Image in Memory,” on view at the Met Breuer in New York City until January 12. Though she never exhibited at the Ferus, instead showing at the woman-owned Mizuno Gallery a few doors down, Celmins, who lived and worked in Los Angeles for two decades, was a long-overlooked yet foundational presence in the 1970s LA art world. She is a painter whose skill with oils—and other mediums like graphite and charcoal—is a pleasure to observe; Celmins’s work flirted with both pop and photorealism, two styles of painting that require a technically superlative hand.

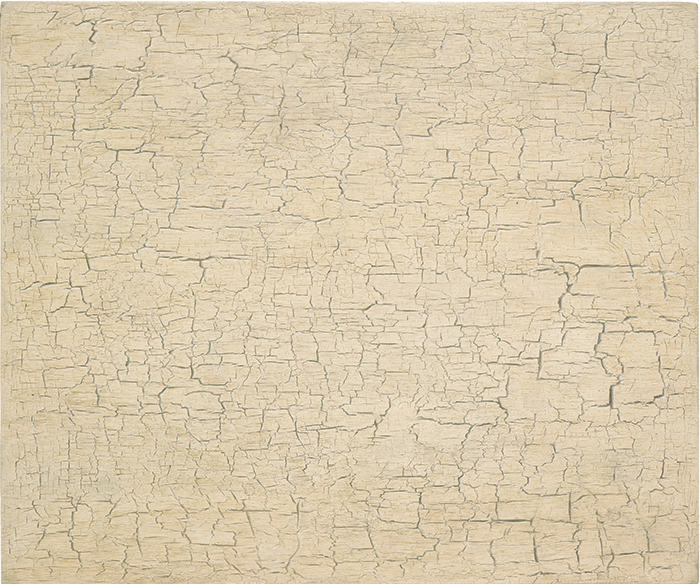

Her deftly painted still lifes and use of photographic references have prompted comparisons to Gerhard Richter and Giorgio Morandi. Her work is characterized by a patient, immersive attention to detail—a mode of looking that activates the most quotidian object or fragment, forcing the viewer to consider its surface and contours. Like Richter, Celmins has painted from news clippings, revisiting her childhood memories of World War II, and she frequently works from photographs, taking the image of the image as her subject. Her later work centers on surface, texture, and imitation, as in her drawings of night skies, spiderwebs, desert grounds, and perhaps most iconically, ocean waves.

I found myself thinking of Babitz when a bit of wall text at the Breuer informed me that Celmins’s somber ocean drawings were made, of all places, in Venice Beach, beginning in 1968. Yes—that Venice. Had Vija lived in Eve’s Hollywood? The grayscale graphite drawings (along with mezzotints, woodcuts, and oil paintings, completed in the 1980s and 2010s) feature the waves of the Pacific Ocean, depicted at a slight distance, the texture of the water completely filling the frame. Yet these are no idyllic seascapes; there is no horizon, no landmark to place the viewer in space. Back in her studio, Celmins carefully rendered the waves in graphite, paying close attention to the tiny particularities of the water, its ripples, highlights, and shadows. She frequently drew from the same reference more than once, as if retelling a story to see if that changed what was said. From a distance, the drawings—charged with graphite’s metallic sheen—look like silvery photographs, fogged over as if with memory’s haze. The drawings have a monumental quietness about them, a silent surface that invites close inspection. Could this really be Venice Beach?

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

The two artists were contemporaries in Los Angeles: While Celmins was beginning her MFA, Babitz was photographed playing chess—in the nude—with Marcel Duchamp. When Celmins first lifted her camera to take a photo of the waves near Venice Beach in 1968, Babitz could very well have been somewhere nearby, painted toes wiggling in the sand. It’s tempting to wonder if the two ever met, if they ever attended the same parties, if Babitz ever stopped by one of Celmins’s openings.

In Slow Days, Fast Company, referring to her own writing practice, Babitz says, “No one likes to be confronted with a bunch of disparate details that God only knows what they mean.” A slapdash quasi-novelist, Babitz’s books aren’t read for the plot (there isn’t any) as much as they are for the spirit of the era they evoke, her beautiful sentences frequently cited in reviews like gleaming nuggets of gold. She recognizes this about her practice, too: “But perhaps if the details are all put together, a certain pulse and sense of place will emerge, and the integrity of empty space with occasional figures in the landscape can be understood at leisure and in full, no matter how fast the company.”

That “certain pulse and sense of place” certainly applies to Celmins’s pieces as well, though in a subtler way than in Babitz’s abundantly social writings. Celmins’s work lives less in the individual movements of her brush or pencil than it does in her movement across multiple works—her choices of composition, repositioning, and framing as she repeats her investigations of a subject with deliberate variations. The pulse is her eye; the place, her mind. In the changing details, one witnesses the moving thought of the artist at work. But unlike the other ’70s California artists that Babitz identifies, Celmins isn’t obsessed with perfection for the sake of a photo finish—she’s no factory-farmed Warhol, no Ruscha. Her obsession with replication is a challenge to memory itself, and to the limits of what we can recreate with the materials at hand. “If you really look at an image…it stays in your memory,” Celmins has said. “So then memory does other things to it. Sometimes a work fades…. Sometimes it stays. Sometimes you have to run back and see if you remember it correctly…. It’s an alive experience.”

The Met Breuer’s retrospective begins on the museum’s smaller fifth floor, which features Celmins’s work prior to 1968. Following her time at UCLA, she was particularly interested in still life, noticing how painting directly from observation might neatly exclude formal questions of expressionism or abstraction. The first room is devoted to her paintings of objects—a heater, a lamp, a hot plate—isolated from context and set against Rembrandt-like backdrops of moody grays and browns. The objects vibrate strangely, viewed as form without function. In the adjoining rooms, Celmins’s still lifes are complicated by the introduction of photographic reference. Here, she engages more directly with the relationship—or lack thereof—between image and content. Drawing on her memories of World War II as the Vietnam War began to escalate, she painted fighter planes suspended in midair, a burning car in the aftermath of an explosion, a news-clipping-esque image of an explosion at sea. These images aren’t Celmins’s but rather images made for the mass consumption of trauma and violence. Yet they are memorialized through her sure and steady brushstrokes, profoundly tragic and mundane at the same time.

Celmins is at her best when confronting the flatness, the thing-ness of photography: how it transmits, duplicates, and crumples. A side room of her early drawings on the exhibition’s first floor places her photographic references—a scene from Hiroshima; a letter from her mother, each postage stamp rendered on a separate piece of paper and carefully affixed—squarely in the middle of the composition, the wrinkles and folds faithfully rendered. In later drawings, as in her moonscapes from 1969 and the early ’70s, the entire rectangle of the paper becomes a way to interpret the photographic space. Images are layered, doubled over, and refracted, not unlike today’s Photoshop tricks. But a painting of a shell from 2009–10, its nubbly texture shaded off gradually with a soft-focus blur, is less interesting, since what it references is a less interesting photograph, too. Set next to the rest of Celmins’s carefully considered body of work, the shell feels more like schlocky photorealism—a 1:1 translation—than the texture of memory.

The show takes its title from To Fix the Image in Memory, a collection of small sculptures created between 1977 and 1982. Displayed in a vitrine on the museum’s fourth floor, the piece features a series of small rocks placed side by side with her handmade duplicates, cast in bronze and painstakingly painted down to the tiniest speck. Head bowed over the vitrine, it was impossible for me to tell which was real and which was constructed. I chose one set, then another, eyes flicking back and forth between each half of a pair, trying to notice a discrepancy until, like a light switch flicking off, I realized I’d slowed down enough to simply enjoy the textures and colors of the rocks themselves. How beautiful a stone could be, I thought, and with such variation.

It’s possible to look at any object in the show for a long time: There is so much to be seen, and each object yields so much on deeper investigation. The close looking that Celmins asks of us can be overwhelming, especially given the exhibition’s scale. But if the rooms begin to blur together—if the ocean waves and night skies and comets begin to layer upon each other—perhaps the work encourages that, too, as the accumulated drawings turn into a kind of palimpsest, a reappreciation and revisiting of the texture of memory, which itself is characterized by how many times we pass over its surface again and again.

For Babitz, the fast company she surrounded herself with was a way to fill the slow, sunny days in a California gleaming with good weather. Celmins, another Los Angeles artist, inverts the motif: Her work is slow company for fast days. Amid a busy world popping and pinging with notifications and headlines, Celmins offers her viewers slow art in a fast time, an opportunity to engage with a body of work for far longer than the lifespan of a tweet. In the slow movement of her canvases, in the generous minutiae of her drawings, Celmins offers us the space to engage with what often feels like the most far-off resource: the attention of our own minds.