Instead of rescuing forgotten truths, neocons like Charles Krauthammer devise novel fallacies.

George Scialabba

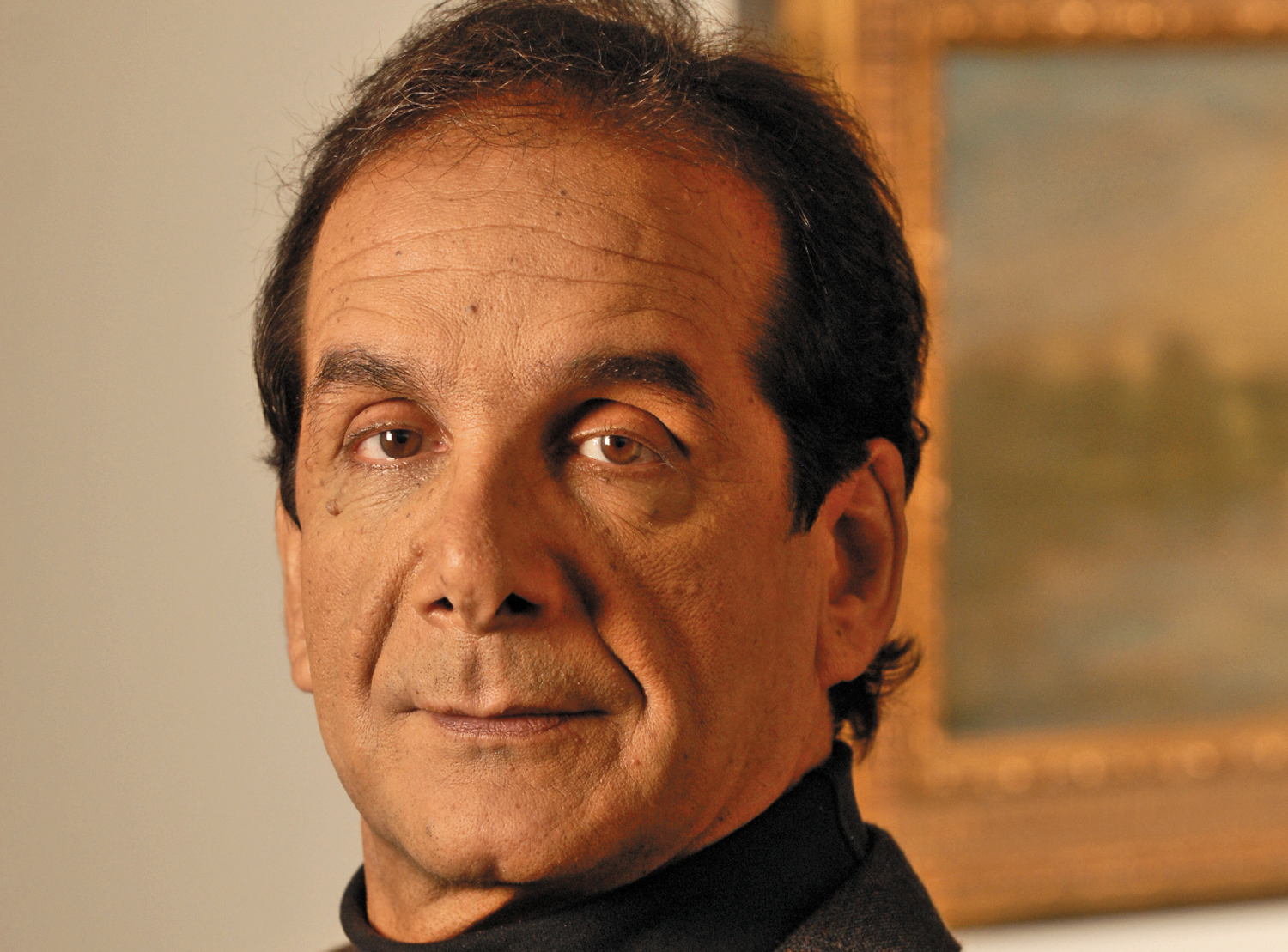

Charles Krauthammer

In his essay on Samuel Taylor Coleridge, John Stuart Mill wrote:

Things That Matter

Three Decades of Passions, Pastimes and Politics.

By Charles Krauthammer.

Buy this book

A Tory philosopher cannot be wholly a Tory, but must often be a better Liberal than Liberals themselves; while he is the natural means of rescuing from oblivion truths which Tories have forgotten and which the prevailing schools of Liberalism never knew…. “Lord, enlighten thou our enemies,” should be the prayer of every true Reformer; sharpen their wits, give acuteness to their perceptions, and consecutiveness and clearness to their reasoning powers. We are in danger from their folly, not from their wisdom; their weakness is what fills us with apprehension, not their strength.

When I first encountered this passage, I agreed wholeheartedly with Mill (though his terminology needs a bit of updating: for “Tories,” read conservatives; for “Reformers,” liberals; for “philosophers,” public intellectuals). These days, I’m not so sure. Conservatism was different in Mill’s time. What he rejoiced at in Coleridge’s example was the prospect of deliverance from “the owl-like dread of light, the drudge-like aversion to change, which were the characteristics of the old unreasoning race of bigots”—Sir Leicester Dedlock, for example, or the Duke of Wellington. A conservative intellectual was virtually an oxymoron before the Industrial Revolution; too much cleverness made a man “unsound.”

Nowadays conservative intellectuals are legion, and some of them are very clever. But they have not become enlightened or enlightening, as Mill hoped. Instead of rescuing forgotten truths, they devise novel fallacies like the efficient markets hypothesis or “Islam’s bloody borderlands.” No longer automatically subversive of authority, the conservative intellectual has become authority’s chief of staff.

Feudalism shunned intelligence; capitalism profits from it—partly by controlling the institutions that manufacture public opinion (advertising, media, publishing, education, research), and partly by cultivating talented individuals with suitable values and views. According to the pioneering political scientist Harold Lasswell, the advent of modern society “compelled the development of a whole new technique of control, largely through propaganda…. the one means of mass mobilization which is cheaper than violence, bribery or other possible control techniques.” Irving Kristol, propagandist par excellence, foresaw that “intellectuals would move inexorably closer to the seats of authority” and devoted his long career to furthering that rapprochement, recruiting lavish support from an anxious business class for the right kind of intellectuals. The contemporary neoconservative intelligentsia, including Charles Krauthammer, is the result.

Krauthammer, an internationally syndicated Washington Post columnist, Time essayist, and frequent guest on Fox and other networks, is quite possibly the most respected neoconservative public intellectual. On the occasion of Krauthammer’s first collection, Cutting Edges (1985), Michael Walzer praised the author as “intellectually tough and morally serious” (exactly the qualities whose absence on the left Walzer complained of in his widely discussed essay “Can There Be a Decent Left?”). In 1987, Krauthammer was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for his “witty and insightful columns on national issues.” And according to Henry Kissinger, Krauthammer’s latest collection, Things That Matter—with its “learned examinations of history and policy”—demonstrates its author’s “sharply honed analysis, humane values and questing mind.”

High praise, though it withers a little under the heat of this blast from the as-yet-unreconstructed Christopher Hitchens:

In the charmed circle of neoliberal and neoconservative journalism, “unpredictability” is the special emblem and certificate of self-congratulation. To be able to bray that “as a liberal, I say bomb the shit out of them” is to have achieved that eye-catching, versatile marketability that is so beloved of editors and talk-show hosts. As a lifelong socialist I say don’t let’s bomb the shit out of them. See what I mean? It lacks the sex appeal somehow. Predictable as hell.

Picture, then, if you will, the unusual difficulties faced by Charles Krauthammer, newest of the neocon mini-windbags. He has the arduous job, in an arduous time, of being an unpredictable conformist. He has the no less demanding task of making this pose appear original and, more, of making it appear courageous. At a time when the polity (as he might well choose to call it) is showing signs of Will-fatigue, it can’t be easy to write an attack on the United Nations or Albania or Qaddafi and make it seem like a lone, fearless affirmation. An average week of reading The Washington Post Op-Ed page already exposes me to appearances from George Will, William F. Buckley Jr., Jeane Kirkpatrick, Norman Podhoretz, Emmett Tyrrell, Joe Kraft, Rowland Evans and Robert Novak, and Stephen Rosenfeld. Clearly its editors felt that a radical new voice was needed when they turned to the blazing, impatient talents on offer in The New Republic—and selected Krauthammer. I dare say Time felt the same way when it followed suit. We live in a period when a chat show that includes Morton Kondracke considers that it has filled the liberal slot.

Krauthammer can dish it out, too: he is a savage scoffer and a merciless mocker (though hardly in a league with Hitchens). He is a commercial as well as a political success: Things That Matter topped the New York Times bestseller list last fall for ten weeks. Facility in framing the conventional wisdom, however vacuous, with perfect assurance—indeed, with an edge of impatience in one’s voice that such truisms need to be explained at all—is a singular gift, and probably the supreme qualification for an op-ed columnist or talk-show guest. But Krauthammer has paid the unavoidable price for composing too many 1,000-word essays for Time, 800-word columns for The Washington Post and 20-second sound bites for Fox News. There is very little intellectual tension, dialectical drama or sense of discovery in his arguments, and very little rhythm, color or finesse to his prose. He floats like a vulture, stings like a jellyfish.

* * *

Krauthammer does have his amiable side (or corner). The first section of Things That Matter, labeled “Personal,” contains a few affectionate portraits: of his older brother; of a kindly dean who made it possible for him to continue in medical school after a paralyzing accident; of a beloved, famously eccentric mathematician; of an obscure major-league baseball player’s brief, brilliant comeback several years after an initial flop. But these ingratiating pieces are few and a little awkward. Lightness of touch doesn’t come naturally to Krauthammer; he’s too embattled.

The object of his hostility is… why, you, dear Nation reader. I suspect that if Krauthammer were asked to sum up everything he stands against intellectually in two words, they would be “The Nation.” Virtually every position regularly espoused in this magazine, and on the left generally, comes under his fire. Even where there is a measure of agreement—sexual equality, gay marriage, stem-cell research, evolution—it is grudging and usually accompanied by a rebuke to callow radicals. When it comes to political economy and, especially, foreign policy, Krauthammer’s contempt is unabashed.

Sometimes it unhinges him. One column tells of a ’60s radical who took part in a bank robbery in which a policeman was killed. She escaped, became a chef, lived undetected for twenty-three years and finally turned herself in. The moral of the story, according to Krauthammer: “It starts with people power. It ends in polenta. A fitting finish to the radical ’60s.” Another column sensitively discusses the case of a 39-year-old woman who gave birth at home using a lay midwife and whose baby died. “It was about the mother’s karma,” Krauthammer sneers. “It was about the narcissistic pursuit of ‘experience,’ the Me Generation’s insistence on turning every life event—even those fraught with danger for others—into a personalized Hallmark moment.”

As these jibes suggest, the Hammer strikes hard, though not always discriminatingly. He is tough, all right, and excruciatingly serious, though not quite in the complimentary sense that Walzer meant those epithets. Still, he is not merely provoking but—unlike his less acute comrades George Will, William Kristol and David Brooks—often thought-provoking as well. Because he fiercely despises left-wing opinions rather than, like Will et al., smugly ignoring them, he has a nose for their weaknesses. Which is, after all, a blessing, however bitter, for those of us who profess them.

He is furious, for example, at the suggestion that the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s arrival in the New World should be an occasion for “repentance and reflection” about the unhappy (for its inhabitants) sequel. “For the left,” he jeers, the anniversary “comes just in time. The revolutions of 1989 having put a dent in the case for the degeneracy of the West, 1992 offers a welcome new point of attack.” True, mistakes were made. “The European conquest of the Americas, like the conquest of other civilizations, was indeed accompanied by great cruelty. But that is to say nothing more than that the European conquest of America was, in this way, much like the rise of Islam, the Norman conquest of Britain and the widespread American Indian tradition of raiding, depopulating and appropriating neighboring lands.” Besides, he concludes, “the real question is, What eventually grew on this bloodied soil? The answer is, The great modern civilizations of the Americas—a new world of individual rights, an ever-expanding circle of liberty.”

Was there really nothing special about the conquest of the Americas? By the end of the nineteenth century, the indigenous population had shrunk by 90 percent, according to some estimates, with 95 percent of its land lost through violence or fraud. Millions were enslaved; hundreds of tribes, languages and cultures in both hemispheres simply disappeared. Nothing on this scale happened during the rise of Islam or the Norman conquest of England, much less in pre-Columbian America. The “circle of liberty” did not expand for most of the population of South America until quite recently, as US dominance declined. And even where it did expand—among the white population of the United States in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries—the expansion turned erratic as the society was regimented by mass production, plundered by a rising finance capitalism, and battered by storms of political hysteria.

* * *

Still, some deep and troubling questions lurk beneath Krauthammer’s crass celebration of America’s manifest destiny. The flowering of equality, self-reliance and civic virtue in the nonslave states from the mid-eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth century is one of the political wonders of the world, a signal achievement in humankind’s moral history. It was made possible by a great crime: it all took place on stolen, ethnically cleansed land. Likewise that other pinnacle of political enlightenment, Athenian democracy, which rested on slavery. But in both cases, didn’t the subordination or expropriation of the many allow the few to craft social relations from which the rest of the world has learned invaluable lessons? Is some such stolen abundance or leisure a prerequisite of moral and cultural advance? Even if we acknowledge the dimensions of the crime, can we really regret the achievement? Krauthammer is no help in answering such questions, but he is clever enough (and truculent enough) to force them on our attention.

Krauthammer is an unapologetic, even strident hawk. He chides Jeane Kirkpatrick, no less, for suggesting that after the breakup of the Soviet Union, the United States might become “a normal country in a normal time.” On the contrary, he admonishes, we live in a permanently abnormal world. “There is no alternative to confronting, deterring and, if necessary, disarming states that brandish and use weapons of mass destruction. And there is no one to do that but the United States,” with or without allies. Of course, there is no question of deterring or disarming the United States. The very idea is outlandish: America is uniquely benign and that “rarest of geopolitical phenomena,” a “reluctant hegemon” almost quixotic in its “hopeless idealism.” Only twisted leftists would deny that freedom is “the centerpiece” of American foreign policy.

The United States, it is true, has no concentration camps or overseas colonies, and our government regularly proclaims its devotion to freedom. For Krauthammer, those facts evidently outweigh our having subverted dozens of governments, many of them democratically elected, and supported dozens of others that were not democratically elected at all, with the only consistent motive being the promotion of a favorable investment climate for American business. Actual history is thin on the ground in Things That Matter.

Even so, there’s a shred of plausibility to Krauthammer’s arrogant unilateralism. He proposes an interesting coinage, the “Weapon State”: a category of anomalous states with little popular support, shallow historical roots, weak civil societies, unbalanced economies, overdeveloped militaries, and powerful grievances or militant ideologies. They are not what social scientists call “rational actors.” Such states, Krauthammer argues, may well have fewer inhibitions about using weapons of mass destruction or massacring civilians on a vast scale than more developed and democratic states. Iraq under Saddam Hussein is Krauthammer’s prototype of a Weapon State; North Korea and Libya are other examples. Because nuclear emergencies or ongoing genocide may require instant response, and Security Council action may be delayed or vetoed by a single major power, a status quo hegemon may be a good thing to have on hand in certain circumstances.

International law is currently a weak reed, and international institutions are mostly dysfunctional. Might not the United States sometimes have to act unilaterally to save innocent lives or keep the peace in a supreme emergency? It is true (though you won’t learn it from Krauthammer) that the United States has done a great deal to undermine international law and institutions, having used weapons of mass destruction for political purposes (Hiroshima and Nagasaki); supported their use by client states (Saddam’s Iraq against Iran); approved the slaughter of civilians on a vast scale by other clients (Indonesia in 1965 and again in East Timor; Turkey against the Kurds); ignored an adverse judgment of the International Court of Justice (which ordered the United States to pay reparations for its aggression against Nicaragua); and repeatedly declared its readiness to use force without Security Council authorization, in defiance of its most important treaty obligation, the United Nations Charter. But so what? Even bad governments can do good things, sometimes even for bad reasons. The fact that the United States killed 1 million or more Indochinese civilians during the 1960s and ’70s and bombed to the ground virtually every structure in North Korea during the 1950s does not disqualify it from saving civilians in Rwanda, Darfur or Congo. Legality is very important, but not all-important.

* * *

Occasionally, Krauthammer is interestingly and usefully wrong. More often, though, he is tiresomely and mischievously wrong. His misconceptions begin with the Cold War. “Where would Europe be,” he demands, “had America not saved it from the Soviet colossus?” In fact, after World War II, the Soviet Union desperately sought a demilitarized Germany, having twice in three decades nearly been annihilated by that country. It offered to withdraw and allow free elections in a unified Germany in exchange for a guarantee that Germany would not be part of a hostile military alliance and that the Soviets would have a veto power over major foreign-policy decisions in the Eastern European countries—a kind of Soviet Monroe Doctrine. The United States, then enjoying a monopoly on atomic weapons, refused. Germany remained divided and the Red Army remained in Eastern Europe.

The Evil Empire never ceased its menacing machinations, and by the early 1980s cowed liberals were duped into supporting a nuclear freeze, “a form of unilateral disarmament in the face of Soviet nuclear advances,” according to Krauthammer. In fact, US nuclear superiority at that point (and throughout the Cold War) was unchallenged. Soviet “advances” almost always followed, and responded to, American advances; and most of the disarmament initiatives, including a self-imposed unilateral test ban in the 1980s—unilateral because the Reagan administration refused to follow suit—came from the USSR. Moreover, as sensible people understood, the probability of a lethal accident involving nuclear weapons had become terrifyingly high by the time the Cold War ended. According to a Brookings Institution study, the United States alone experienced nineteen nuclear alerts between 1946 and 1973. On two occasions—one for each side—a large-scale missile attack following a false warning of incoming enemy missiles was aborted within minutes of launch. Eric Schlosser reports in Command and Control that 1,200 nuclear weapons were in some way involved in accidents during the first two decades of the Cold War, at least two of which nearly caused catastrophic damage within the United States. As a former head of the US Strategic Command remarked: “We escaped the Cold War without a nuclear holocaust by some combination of skill, luck, and divine intervention, and I suspect, the latter in greatest proportion.”

About Central America, Krauthammer resorts to brazen falsification. Reagan’s so-called “illegal war,” he writes, was really “an indigenous anti-communist rebellion that ultimately succeeded in bringing down Sandinista rule and ushering in democracy in all of Central America.” In reality, throughout the twentieth century, the United States supported business-friendly oligarchies and military dictatorships that violently suppressed all democratic stirrings. When Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza was overthrown (with US support continuing to the bitter end), the CIA assembled, trained and paid thousands of former Nicaraguan National Guardsmen on either side of the Honduran border. There was no “indigenous anti-communist rebellion”; these Contras went on a rampage, torturing and murdering peasants and sabotaging agricultural collectives. During this onslaught, a national election was held—one that was far more democratic than any the country had seen under Somoza. The Sandinistas won, after which the United States organized an illegal international embargo that, as with Cuba, bled the country dry. As for the right-wing forces the United States supported in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, they were, if possible, even bloodier and crueler than the Contras.

Unsurprisingly (he began his career at The New Republic, after all), Krauthammer is less than wholly objective about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. There would be no conflict, he insists, but for “the long history of Palestinian rejectionism”; talk of Israeli “intransigence” is “mindless.” His prime exhibits in evidence are the “three times” since 1994 when “Israel has offered the Palestinians land for peace…. And been refused every time.” These three occasions are Camp David (2000), Taba (2001), and a mysterious episode in 2008 when Ehud Olmert allegedly made an “incredible” offer, an “ultimate capitulation to Palestinian demands.” Each time, Krauthammer charges, the Palestinians walked away. They have never wanted a “final peace” if it meant “reciprocal recognition of a Jewish state.” They prefer “an independent Palestine in a continued state of war with Israel.”

Matters are not nearly so simple. At Camp David, Krauthammer writes, Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak offered PLO leader Yasir Arafat “a Palestinian state on the West Bank and Gaza—and, astonishingly, the previously inconceivable division of Jerusalem. Arafat refused.” What Barak actually offered was a West Bank divided into three cantons separated by salients containing 12 percent of the land and the vast majority of existing Israeli settlements; continuing Israeli control of the water resources; a Palestinian capital in Abu Dis, a village adjacent to Jerusalem; virtually no provision for Palestinian refugees; and an agreement that UN Resolutions 194 and 242 should no longer apply to the conflict. What is “inconceivable” is that anyone but a hasbarist would portray this as a reasonable offer.

Clinton was disgusted by Barak’s fakery and proposed an alternative, which formed the basis for discussions at Taba a few months later. Krauthammer calls this “an even sweeter deal,” which Arafat again refused out of hand. In reality, the Palestinians did no such thing. Nor was it a sweet deal or even a genuine offer; it was a campaign ploy. According to Israeli journalist Tanya Reinhart:

There was not even a serious attempt to hide the fact that these talks were part of the election campaign. “A senior source in Prime Minister Ehud Barak’s office says the purpose of the Israeli-Palestinian marathon talks starting on Sunday at Taba is to neutralize the Israeli Left….” It was clear from the start that the purpose of the talks was to produce some optimistic “statement for the press,” a goal that was essentially obtained: “Ehud Barak sent the leaders of the Left—Shlomo Ben-Ami, Yossi Beilin, and Yossi Sarid—to Taba, with the aim of attaining an ‘endorsement’ for his candidacy from the Palestinian Authority…. The three emissaries succeeded in fulfilling their mission. They convinced Abu Ala and his colleagues to sign a declaration stating that the two sides ‘have never been closer to reaching an agreement.’”

According to another Israeli journalist, there was clearly a “determined decision made by Barak not to reach a settlement with the Palestinians in the time that is left until the elections.” In any case, the Israeli offer at Taba differed very little from the one at Camp David: it too called for annexation of the settlements and surrounding land, though somewhat less of it; no Palestinian sovereignty over East Jerusalem; and barely any notice of the refugee problem.

About Olmert’s “incredible” secret offer in 2008, little was known for several years. Last May, a report appeared in The Jerusalem Post with new information. Krauthammer’s claim that “every settlement remaining within the new Palestine would be destroyed and emptied” turns out to be inaccurate. Olmert proposed to keep 6 percent of the West Bank, including the largest settlements, still cutting the West Bank into three parts. Several Palestinian holy places would be returned or internationalized, which definitely did not amount to the “division of Jerusalem,” as Krauthammer thinks. And 1,000 Palestinian refugees—out of some 5 million—would be repatriated to Israel each year for five years. It was extraordinarily credulous of Krauthammer to imagine that Olmert, who in 2006 announced his intention to carry out Ariel Sharon’s plan for greatly expanding existing settlements in the West Bank, should only two years later have proposed dismantling every single one of them.

In the overcharged ideological atmosphere of Things That Matter, atheism and even veganism are suspect. Krauthammer summons us to remember the wise observation of Arthur Schlesinger (“and many others”) that “declining faith in the supernatural has been accompanied by the rise of the monstrous totalitarian creeds of the 20th century.” For “as Chesterton put it,” Krauthammer continues, “‘The trouble when people stop believing in God is not that they thereafter believe in nothing; it is that they thereafter believe in anything.’ In this century, ‘anything’ has included Hitler, Stalin and Mao.” It has also, I would remind him, included Bertrand Russell, Albert Einstein and Albert Camus.

And beware the moralizing tyranny of liberal educators: having replaced soulcraft with hygiene, they are scheming at this very moment to “teach your kids safe sex, take Alar off their apples, feed them yogurt and broccoli for lunch and, for the ride home, lash them to their safety seats in cars with mandatory air bags.” There is no end to this pernicious liberal nonsense, Krauthammer warns: witness “the mania for health foods,” which “feeds a nutritional fanaticism and fastidiousness that make Islamic and Jewish dietary prohibitions look positively, well, liberal.” Actually, as a practicing vegetarian with an Orthodox friend who observes Jewish dietary laws in their full rigor, I can assure Krauthammer that his concern for us deluded health food maniacs is misplaced.

For the tragic waste of Krauthammer’s considerable talents represented by Things That Matter, a good deal of the blame should doubtless go to the bad habits fostered by op-ed writing and talk-show commenting. Krauthammer is an expert simplifier, summarizer and close-quarters scrapper. His skill at producing zingers is enviable. But remarks are not literature, and zingers are not political wisdom. You can’t surprise yourself, breathe deeply and get to the bottom of things in 800 words or twenty seconds.

By and large, the quality of the eighty-eight pieces in Things That Matter is proportional to their length. Hearteningly, Krauthammer mentions that he is, at long last, writing a book: two books, in fact, one on domestic policy and another on foreign policy. Perhaps in the course of them he will, at least occasionally, surprise himself and us, vindicating Mill’s generous hope.

George ScialabbaGeorge Scialabba’s selected essays, Only a Voice, will be published in August by Verso.