Last November, an extraordinary coalition of groups from across the political spectrum helped push Florida’s Amendment 4, which restores voting rights for the nearly 1.4 million Floridians with felony convictions in their past, across the electoral finish line.

Constitutional amendments need at least 60 percent support to become law in Florida. In the final tally, Amendment 4, which allows all felons except those convicted of murder or sex offenses to apply for restoration of their voting rights upon completion of their sentence, got nearly 65 percent backing—1 million more votes than any political candidate received in the state’s elections that year. Florida voters—across racial, economic, and party lines—came out in favor of reenfranchisement.

“The idea of second chances, it resonated with people. People could connect to that. People were going to vote for their neighbors, friends, family members, not for a partisan agenda or an ideology. It was built on the lines of humanity, not something else. That was cool. It helped break through the noise of today’s politics,” said Neil Volz, one of the leading spokespeople for the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, a grassroots group representing “returning citizens”—ex-prisoners and other felons.

Volz is a former Washington lobbyist who played a key role in the Jack Abramoff scandal and received a felony conviction for conspiracy. A hefty, bespectacled, bearded man, Volz went from being a highly paid Washington insider to being a felon, shunned by his erstwhile colleagues. Although he didn’t spend time behind bars, he was sentenced to probation and community service and was fined for his actions.

Trying to start his life afresh, Volz moved to Central Florida, aware that in doing so, he was relocating to one of a handful of states that locked felons into permanent second-class citizenship, making it all but impossible for them to vote again. He picked up minimum-wage work as a janitor and in his spare time, along with some friends he made who had also lost their right to vote, began traveling around the state, talking to people about the need for second chances and the injustice of permanent disenfranchisement.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Desmond Meade was one of those friends. He, too, was a felon. Unlike Volz, however, Meade had also been an addict, a prisoner, and after he was freed from prison in 2004, homeless. Somehow, he pulled out of the dive toward self-destruction, and, as he put the pieces of his life back together over the next decade, went to college and became involved in politics.

Meade eventually studied law and began trying to get his civil rights restored so that he could be admitted to the Florida bar. But like so many other ex-offenders seeking clemency—more than 10 percent of voting-age US citizens are disenfranchised—he found it akin to butting his head against a wall. The would-be lawyer got tired of watching Florida Governor Rick Scott slow-walk the process. (Scott was governor from 2011 to January of this year, when he began serving as US senator, the position he won last fall.) Meade became disillusioned about the prospect of legislative change, since time and again Florida lawmakers found reasons not to alter the Jim Crow–era disenfranchisement codes, enacted in 1868. Finally, Meade decided to take the fight to the people, building up a formidable network of groups that could argue the case directly to Florida voters.

By 2018, the coalition backing Meade’s Amendment 4 included the FRRC, Floridians for a Fair Democracy, the ACLU, the Advancement Project, the National LGBTQ Task Force, the Florida Dream Defenders, local trade unions, and the Florida League of Women Voters. These groups had long argued for reenfranchisement. But Meade’s network also included some overtly conservative organizations, including the Christian Coalition and Charles and David Koch’s Americans for Prosperity.

For Allison DeFoor, a conservative priest and formerly a sheriff of Key West, judge, and state-GOP activist, this was about finding a way to anchor returning citizens to the community. “Jobs are good, families are good, church is good, voting is good. Anything that ties a person to his community is a good thing,” he said.

It’s a sentiment that St. Petersburg resident Lisa Trunzo, once a prisoner and drug addict and now a nurse in the Veterans Affairs system, heartily agreed with. Drinking a coffee in a fashionable café downtown (her right forearm tattooed with the Beatles lyric “Take these broken wings” and her left arm finishing the line “and learn to fly”), she spoke of how she has made sure to vote in every election since she received clemency from then–Governor Charlie Crist in 2007. “I don’t mail it in,” she said adamantly. “I go in person and stand in line. I feel proud to do that. I want to experience it. I don’t want to be kept in my place in any way. I don’t want to be denied any right anybody else has. How do you justify taking taxes out of someone’s pocket who doesn’t have a say?”

In the run-up to last year’s vote, there was astonishingly little organized opposition to Amendment 4—perhaps a reflection of the new national mood supporting criminal-justice reform and the recognition that mass incarceration comes with a lot of collateral damage, not least the removal of millions of Americans from the voter rolls. While many Republican politicians expressed reservations about the scope of the reenfranchisement, few came out explicitly against the ballot measure. Even gubernatorial candidate Ron DeSantis, who won on a Trumpian platform in the same elections in which Amendment 4 was passed, remained publicly neutral.

“It was a very easy thing to get behind,” said evangelical pastor Chad Woolf, sitting in his book-lined office in the Christ Community Church in Fort Myers. He has a long history of working with the city’s addicted and homeless populations, and despite his conservative politics, he strongly believes in second chances. “I preach about redemption all the time,” he said, smiling as he talked. “Every person is made in God’s creation, and God wants to redeem everyone. Why wouldn’t I apply that to people’s lives?”

Woolf pooh-poohed the notion that reenfranchisement would help only the Democrats. After all, he noted, despite the disproportionate imprisonment of black and brown men, more whites than blacks commit felonies. The Florida Department of Corrections estimated that roughly 40 percent of current inmates in Florida are white men and nearly 9 percent are white women—and historically, lower-income whites in Florida have been a reliably conservative demographic. There are no accurate tallies of the racial breakdown of the 1.4 million felons, disenfranchised over many decades, now eligible for reenfranchisement under Amendment 4, though criminal-justice experts in the state believe a majority are likely white. But the racial demographics and how the reenfranchised will cast their votes are, to Woolf, largely irrelevant. “Who cares?” he asked. “Voting is a fundamental right as a citizen. We should be encouraging as many citizens to vote as possible.”

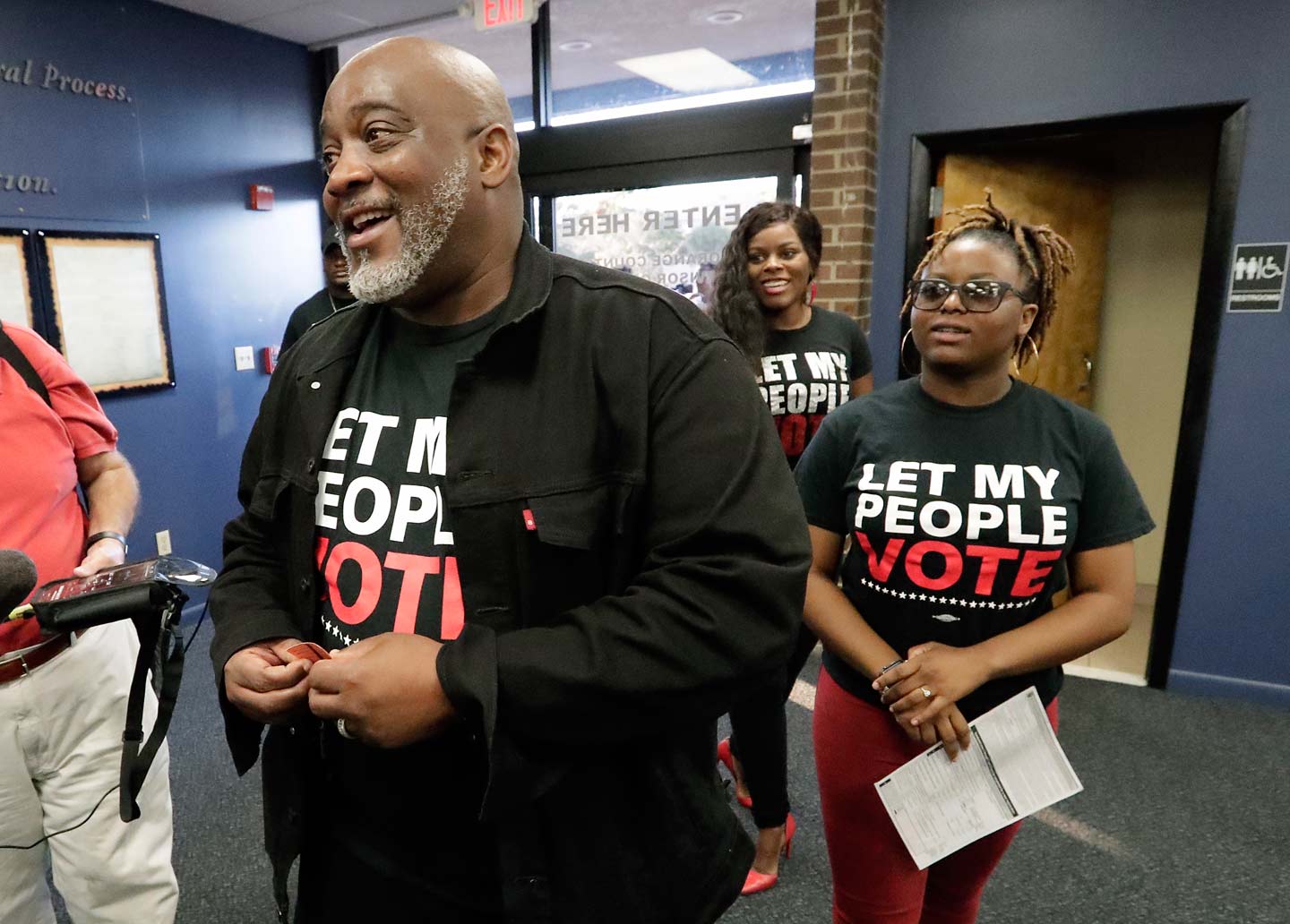

Two months after amendment 4’s passage, supervisors of elections in Florida counties began voter registration for felons who completed their sentences. In those first days, thousands filed the paperwork to get their right to vote restored. There was an atmosphere of exhilaration. “I was one of the first people to register,” Meade said with enthusiasm. “I received, a few weeks later, my voter-registration card.”

For the 51-year-old Meade, who last voted in the late 1980s, it was the emotional culmination of years of struggle. “I’m very proud to have it,” he said. “Nothing speaks more to citizenship than being able to vote. It restored my citizenship to me. It was a very humbling experience. Oh, man, when I got the voter-registration card in the mail, tears came to my eyes. It speaks volumes. It says I have a voice now.”

But then things got squirrelly. Florida Secretary of State Laurel Lee and GOP legislators began a chorus of complaints about the need for legislation to help interpret and implement the amendment, despite the fact that it was worded to be self-implementing, and DeSantis started sending out signals that he wanted some legislation that he could sign on the issue.

This spring, State Representative James “J.W.” Grant from Tampa and State Senator Jeff Brandes from St. Petersburg introduced legislation to “clarify” the intent of the voters who passed Amendment 4. It called for the payment of all financial penalties—even if a judge converted those penalties into civil liens—before a person could apply for restoration of voting rights. If a felon in Florida has completed the other terms of his or her sentence and is making a good-faith effort to pay off financial penalties, judges often convert the remaining debt to a civil lien. The money is still owed, and usually a monthly payment plan is set up, but it is removed from the criminal-court setting and is considered a civil matter. In the past, having an outstanding civil lien was not considered an indication of an incomplete sentence.

In practice, therefore, the new legislation would redefine “completion of sentence” in a particularly coercive manner that would permanently exclude many poor felons from getting their vote back. (Earlier versions of the bill would have significantly expanded the definitions of “murder” and “sex offenses” so as to render more felons ineligible for vote restoration, but this language was removed before the measure was voted on.)

Ironically, Brandes had gained considerable credibility with criminal-justice reformers in recent years by pushing legislation to cut back the state’s growing prison population. This time around, however, he sided firmly with the tough-on-crime, tough-on-criminals side of the debate. Brandes, Grant, and several other GOP legislators involved in this process did not respond to The Nation’s repeated requests for comment.

The ACLU and the FRRC estimated that as a result of the passage of Brandes and Grant’s legislation, instead of 1.4 million felons being eligible to vote, it could be only 800,000. Others put the number even lower. In the end, it’s guesswork, because there are no accurate databases of the numbers of felons who still owe money as a result of criminal conviction.

DeSantis has given conflicting indications about whether he will sign the bill, though in early May he publicly promised to do so. The League of Women Voters and other voter-registration groups have, however, already noted a chilling effect. People are scared of even beginning the reenfranchisement process, fearing that in doing so they would run afoul of the possible new law. “People are trying to get back in the game,” said activist and onetime prisoner Brother John Muhammad in St. Petersburg. “And people are not willing to take a chance of breaking the rules by registering to vote.”

“I got a phone call just the other day,” recalled Panama City–based civil-rights attorney Cecile Scoon, who serves as the Florida League of Women Voters’ action chair for Amendment 4. “They were fearful of registering to vote because of the new [bill]. Many league members are getting these comments when we’re out there trying to register people.”

These developments clearly mock the intention of Amendment 4. True, during the campaign some supporters, including John Mills, a former speaker of the Florida House of Representatives, said that all parts of a sentence, including the payment of fines, fees, and restitution, had to be completed before a person could register to vote. But none talked about including civil liens in that requirement. Even during Scott’s tenure as governor, the Clemency Board never used felons’ civil liens as a reason to deprive them of clemency.

“Our legislators are elected officials, and they are thwarting the will of voters,” argued Patricia Brigham, the Orlando-based president of the Florida League of Women Voters. “This is not what the voters approved. At the 11th hour, in a nighttime session, legislators pushed this bill through. This is not how a transparent government behaves. They’ve created this messy, sticky situation there is no need for. This is voter suppression, plain and simple. These are poll taxes.”

“It was completely unnecessary,” said Micah Kubic, the executive director of the Florida ACLU, speaking in a fourth-floor conference room at the organization’s Miami headquarters. With his shock of ginger hair, checked golf pants, and yellow polka-dot tie adorned with dinosaur decals, he looked the part of a theatrical litigator, and as he talked, his voice got more animated. “The bill that was passed raises serious legal issues, especially the idea that your ability to pay is going to determine your ability to vote…. It is clear the bill they passed violates some of the text and the spirit of the amendment. When you do that, you should expect legal challenges.”

As DeSantis pondered whether to sign the legislation in the governor’s office in Tallahassee, Angel Sanchez sipped a green-tea Frappuccino at a Starbucks in the swanky Miami neighborhood of Coral Gables. Sanchez, 37, is studying law at the University of Miami. He was dressed casually in jeans and boots to protect against rain squalls that morning, and on the front of his T-shirt were the words “Yes to second chances.”

By most measures, he was an improbable candidate for success. He grew up in Allapattah, Little Havana, and other poor neighborhoods of Miami. His mother was addicted to drugs, his immigrant father worked long hours as a tow-truck driver, and from the time he was a third-grader, Sanchez was in trouble with the law. He got into fights, joined violent street gangs, and garnered a reputation for “robbing dope boys,” he said. He eventually moved from carrying knives to carrying guns, and as he entered his teens, he got arrested for progressively more serious, more violent crimes. At the age of 17, he was convicted of two attempted murders and sentenced to 30 years behind bars.

But inside the nine prisons where he did time over the following decade, something clicked for him. He started to talk with older, more political inmates, taking suggestions from them about books to check out of the prison library. He read about the 1971 Attica uprising, about George Jackson and the Soledad Brothers. Sanchez discovered, sitting in his cell, that he had a passion for the law, and he started researching community colleges for that distant day when he would be eligible for release. Eventually, he began to file legal motions to get his sentence reduced, and after numerous attempts finally managed to get a reduction to 15 years.

After more than a decade behind bars, in 2011 he was released, with 10 years of probation tacked on. He moved to a Salvation Army shelter in Orlando, got part-time work in a fast-food restaurant, and began the arduous process of applying to a local community college.

Over the following years, he thrived academically. He won several awards and prestigious scholarships, enrolled at the University of Central Florida, and so impressed a local judge that she not only scrubbed his probation period but also offered him an internship. Sanchez set to work on an honors thesis about felon disenfranchisement in Florida and its impact on the state’s Latino population. It was through that research that he met Meade and joined the reenfranchisement movement.

Sanchez knew the impact of disenfranchisement firsthand. By then, he was in his mid-30s and was preparing to apply to law school. Yet under Florida law, he couldn’t vote. Nor would he even be eligible to apply to the Clemency Board, on which sat the governor and two cabinet members, for a restoration of his civil rights until seven years after he had come off probation. And like other felons, he couldn’t be licensed to practice an array of professions, including the law, until he was granted clemency.

In 2000, when there were more than three-quarters of a million disenfranchised Floridians, mass disenfranchisement almost certainly affected the outcome of the closely fought presidential race between George W. Bush and Al Gore, who were separated by only about 500 votes in the Sunshine State. Since then—despite Crist’s governorship from 2007 to ‘11, when he granted clemency and the restoration of voting rights to about 150,000 people—an additional 700,000 people, give or take, lost their right to vote. That was one of the consequences of tough-on-crime policies. Under Scott, only about 3,000 people managed to get their right to vote restored.

Amendment 4 was supposed to end the crushing burden of mass disenfranchisement in Florida. “We brought to the forefront of the debate the reenfranchisement movement,” Sanchez said. “We did that in Florida.”

Now, however, he and other Amendment 4 activists worry that legislators will succeed in chipping away at that accomplishment. They fear that hundreds of thousands of people—like Coral Nichols, a 41-year-old who was convicted of grand theft and wrongful misuse of identity in 2005 and who is paying off $188,000 in fines and other restitution penalties, which have been converted into a civil lien, in $100 monthly installments—will probably never be able to vote.

To counter this, activists are girding for legal battle. If DeSantis signs the bill into law, the ACLU and others will almost certainly file suit the same day to stop it from taking effect. “The legislature may think it’s over because they managed to pass a bill,” said the ACLU’s Kubic. “But it’s not over. This is not a done deal. Our job as a civic ecosystem is to get as many people registered, to participate, to see the stakes, and to hold legislators accountable for all the assaults on civil liberties in this legislative session.”