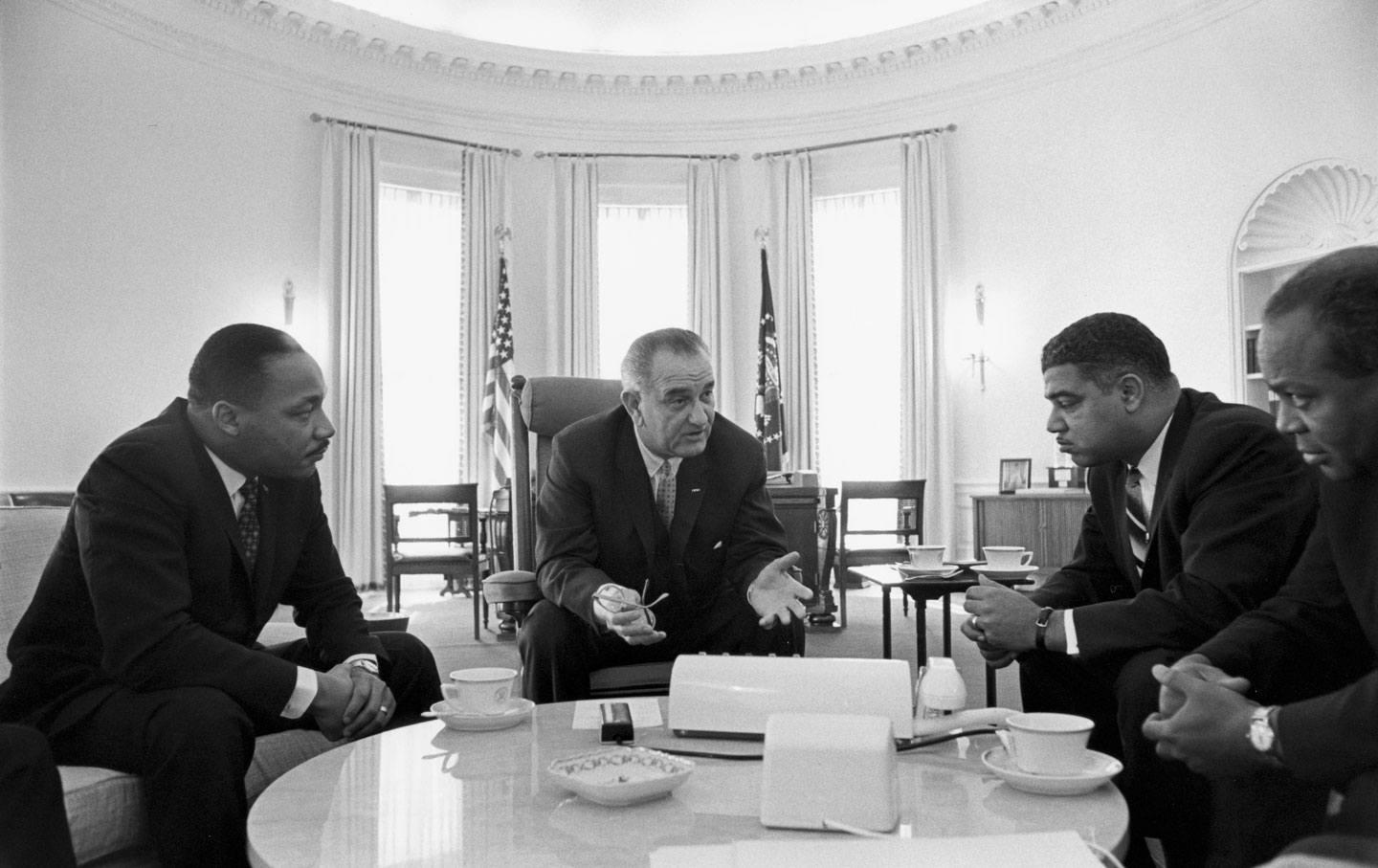

President Lyndon B. Johnson meets with Martin Luther King Jr., Whitney Young, and James Farmer in 1964.(Yoichi Okamoto / Lyndon B. Johson Library)

How did the United States become the world’s biggest jailer? Most accounts of the rise of mass incarceration begin with Barry Goldwater and Richard Nixon, who gained political advantage in the 1960s through racially coded “law and order” electoral campaigns. Republican dominance of the crime issue continued with Ronald Reagan, who aggressively pursued longer prison sentences as part of the War on Drugs, and George H.W. Bush, whose Willie Horton ad against Michael Dukakis lives on in race-baiting infamy. While Democrats play a role in this story, they do so belatedly and defensively, with Bill Clinton’s support for “tough on crime” laws in the 1990s finally neutralizing the Republican advantage on the issue.

In From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime, Harvard University historian Elizabeth Hinton argues that this familiar narrative lets Democrats and liberals off the hook too easily. “As the product of one of the most ambitious liberal welfare programs in American history,” Hinton notes, “the rise of punitive federal policy over the last fifty years is a thoroughly bipartisan story.” In fact, she continues, “crime control may be the domestic policy issue in the late twentieth century where conservative and liberal interests most thoroughly intertwined.”

Hinton makes her case by tracing the evolution of federal law, beginning with President John F. Kennedy’s support for the Juvenile Delinquency and Youth Offenses Control Act of 1961. The legislation, which funded initiatives like job training, medical care, and tutoring programs, seems far from punitive. But Hinton lodges a series of objections, including the law’s assumption that the residents of black ghettoes were pathological, that community-based anticrime efforts in these neighborhoods were flawed, and that salvation depended on the intervention of government social workers and other professionals. Worst of all, she argues, the Kennedy administration used its programs to introduce “soft surveillance” in poor communities. For example, the group Mobilization for Youth ran two coffeehouses for gang-affiliated and other disadvantaged young people on New York City’s Lower East Side. While its activities seem benign—photography and theater classes, chess and checkers—Hinton sees an ulterior motive at work: “Beneath the seemingly natural setting of the coffeehouse was a carefully planned neighborhood center that made it possible for staff to watch troublesome teenagers while simultaneously providing social welfare services.”

Though Hinton is critical of Kennedy, the bigger villain in her story is Lyndon Johnson, whose administration made the fateful turn away from its own War on Poverty and toward the War on Crime. Johnson pushed the Law Enforcement Assistance Act of 1965, which Hinton identifies as the crime war’s opening salvo. The act, which sailed through Congress and was enacted just one month after the Watts uprising, authorized the federal government to help states fight what Johnson called “a war within our own boundaries.” Because wars need soldiers, and soldiers need weapons, it wasn’t long before the federal government began directing funds to local police to buy tanks, military-grade weapons, and helicopters.

Though Johnson never claimed that policing and surveillance should be the exclusive response to crime, that’s where the money went, often at the expense of social-service initiatives. By 1968, antipoverty programs staffed by social workers faced funding cuts and had to vacate their offices in public-housing projects. The spaces didn’t stay empty for long, as neighborhood police stations took their place.

Once Nixon became president, Hinton writes, he wasn’t the law-and-order innovator that many have suggested; instead, he followed in Johnson’s (and, to a lesser extent, Kennedy’s) footsteps. The newly created Law Enforcement Assistance Administration, an outgrowth of Johnson’s Law Enforcement Assistance Act, would prove pivotal. If Johnson developed the idea of funneling federal dollars to states for the War on Crime, Nixon perfected it: During his presidency, the LEAA’s budget grew more than a dozenfold, from $63 million in 1969 to $871 million in 1974. Only about 2 percent of the LEAA’s support for urban police departments went to tenant patrols or other community-based law-enforcement programs. Nixon’s reluctance to fund black-community initiatives was rooted in racism. “There has never in history been an adequate black nation,” Nixon opined to his chief of staff, H.R. Haldeman, “and they are the only race of which this is true.”

Instead, the federal dollars were often invested in militaristic programs like Detroit’s notorious STRESS unit (the acronym stood for “Stop the Robberies, Enjoy Safe Streets”), an aggressive undercover unit that wound up killing 18 people during its first two years in operation, 17 of them black. Violent policing on the front end of the criminal-justice system was accompanied by massive prison building on the back end: The Crime Control Act of 1970 provided funding to states on the condition that they spend at least 20 percent on corrections programs. The prisons themselves were increasingly harsh, as Nixon’s team pressed for more maximum-security facilities.

* * *

By the end of Nixon’s time in office, the foundations of our modern criminal-justice system had been established, and the Ford, Carter, and Reagan administrations simply built on them. Sometimes Hinton describes federal policies that appear well-intentioned but failed to achieve their ends, such as the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act of 1974. Signed by Gerald Ford, the law was meant to ensure that kids who ran away from home didn’t end up imprisoned in facilities along with young people who had committed serious crimes—a good idea, surely, but one that in practice increased racial disparities in youth-incarceration rates. State officials acting on explicit or implicit racial biases ended up diverting white middle-class youths from prison, while poorer young people of color remained behind bars.

Sometimes the dire consequences seemed much more predictable. When the Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984 authorized local police to keep as much as 90 percent of the money and property seized from accused drug dealers, the incentives for mass arrests became overwhelming. In 1988, Miami police arrested 5,000 suspects in a single operation. That same year, after the Los Angeles Police Department’s Community Resources Against Street Hoodlums (CRASH) unit sent 1,000 officers on sweeps through South Central on a single night, 1,400 residents—most of them black—faced charges, mainly for petty offenses like traffic, parking, and curfew violations. The mass criminalization of black America was under way.

Hinton’s careful excavation of the bipartisan federal drivers of mass incarceration is a significant contribution to the scholarly literature. Like Marie Gottschalk (The Prison and the Gallows: The Politics of Mass Incarceration in America) and Naomi Murakawa (The First Civil Right: How Liberals Built Prison America), Hinton challenges the prevailing understanding of mass incarceration’s roots. However, any account of the War on Crime that mainly focuses, as Hinton’s does, on federal policy comes with built-in limitations. Just under 90 percent of American prisoners are housed in state and local jails. State legislatures establish sentence lengths for most crimes, and prosecutors and police forces are overwhelmingly local. For these reasons, I would argue that state and local actors played a more important role than federal ones in constructing the criminal-justice system we live with today. Still, Hinton makes a persuasive case that the federal government has profoundly influenced state and local decisions. The crucial point may be that over the last half-century, actors at every level were insisting on a more punitive direction, and that mass incarceration was the inevitable result.

In leveling her criticisms against Democratic officials, Hinton confronts a further obstacle: Partisan politics and the nature of the legislative process make her causal claim difficult to evaluate. The liberals-did-it-too argument can take various forms, and it’s not entirely clear which version Hinton endorses. One version claims that Democrats would have preferred a less punitive approach, but after recognizing the potency of the crime issue with voters, they capitulated. Another focuses on legislative horse-trading, arguing that liberals typically got something they wanted—such as more money for drug rehabilitation—by letting conservatives get something they wanted, like longer prison sentences. In this version, mass incarceration is partly the result of liberals making bad deals or failing to appreciate the consequences of the legislation they supported. The third version of the argument says that liberals themselves wanted tough-on-crime measures and would have enacted them even if the likes of Goldwater, Nixon, and Reagan had never come along.

The third version is the most provocative, but I have doubts about whether it can be sustained. After all, there’s no question that conservatives ran on a law-and-order agenda while accusing Kennedy, Johnson, and every Democrat who came after them of being “soft on crime.” A 1968 Republican pamphlet called “Crime and Delinquency—a Republican Response” was typical: “The Johnson-Humphrey Administration has proposed its standard ‘great society’ answer to the problem—Federal money and Federal controls…but too many factors indicate that improved economic and social conditions alone will not reduce crime.” Political scientist Vesla Weaver, in her important article “Frontlash: Race and the Development of Punitive Crime Policy,” explains what happened next: “The liberal social uplift approach atrophied under the weight of this powerful doctrine. Sandwiched between two traps—being soft on crime and excusing riot-related violence—liberals had to forgo their ideal positions and moved closer to the conservative position.”

Or consider a more recent example: Bill Clinton’s 1994 crime bill, which reemerged as a topic of debate during this year’s Democratic primary campaign. This tough-on-crime measure was supported by many members of the Congressional Black Caucus. Some of them, like John Lewis, the Georgia Democrat and former leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, initially opposed the act because it expanded the federal death penalty. But Lewis changed his mind after funding for crime prevention was added to the bill. “It’s been one of the most difficult decisions I’ve had to make in the eight years since I’ve been [in Congress],” Lewis said when announcing his support for the bill. “It was much easier to march across the bridge in Selma or go on the Freedom Rides. Everything then was clearly black and white.” While I don’t mean to suggest that all Democrats were as conflicted as Lewis, I suspect that both pressure from the right and legislative compromise explain much of the liberal support for punitive crime legislation.

* * *

Hinton has written a work of history, but most readers will see its contemporary implications as clearly as she does. Having shown how federal policy helped drive up the number of people incarcerated by or under the supervision of the criminal-justice system, she enables us to imagine how it might help bring the numbers down.

First, the federal government should support structural interventions in the economy. This strategy can be boiled down to one word: jobs. The Johnson administration considered such an approach but ultimately pulled back. “Wary of the costs of a major employment initiative, the Johnson administration rejected programs that would have provided actual long-term jobs,” Hinton writes. “Instead, it built from the policies of the Kennedy administration to embark upon a major national program to offer job training to low-income individuals—regardless of whether they could find employment afterward.” Tragically, the Johnson administration’s preference for job training over jobs has become a hallmark of American social policy. But for the millions of unemployed people in America’s poor communities, creating training programs without available jobs is at best a speculative gamble, at worst a cruel hoax.

The second lesson to draw from Hinton’s history is that social-service programs should be run outside the criminal-justice system. Hinton meticulously documents the opposite trend, detailing how robust funding for criminal-justice agencies, combined with meager support for social services, forced providers to become affiliated with law enforcement. A photo of DC police officers playing cards in a “teen center” illustrates the point. There is nothing wrong (and, I would say, a lot right) with cops getting to know neighborhood teens in nonadversarial settings. But the problem arises when—as has happened too often over the past half-century—budget priorities mean that the only community-based youth programs to be found are those closely tied to law enforcement.

Finally, the federal government should understand that, as Hinton argues, “crime control is a local matter,” and that “residents in communities should be responsible for keeping their own communities safe.” I wish she had given a fuller justification of this principle. Her book doesn’t specify the precise allocation of responsibility between local officials and community groups—and because the strategy she favors has never been adopted, she has no way of proving that communities can do a better job policing themselves, even in the face of violent crime, than state or federal authorities. But Hinton does provide many examples of promising community-based programs that didn’t survive because of people like Nixon, with his belief that “there has never in history been an adequate black nation,” or the officials of the Johnson administration who, while less blunt, also viewed poor black communities as pathological. These grassroots programs fell apart when they lost their funding or were forced to surrender their autonomy to government agencies. What if, Hinton asks, we had allowed them to flourish? What if we hadn’t forced them to accept government control? What if we had given them the robust, sustained funding that we gave to the War on Crime?

Such questions about what might have been are unanswerable. But by showing us the wrong turns, Hinton’s careful research points us toward a better path.

James Forman Jr.James Forman Jr. is a professor at Yale Law School. His book Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) will be published next spring.