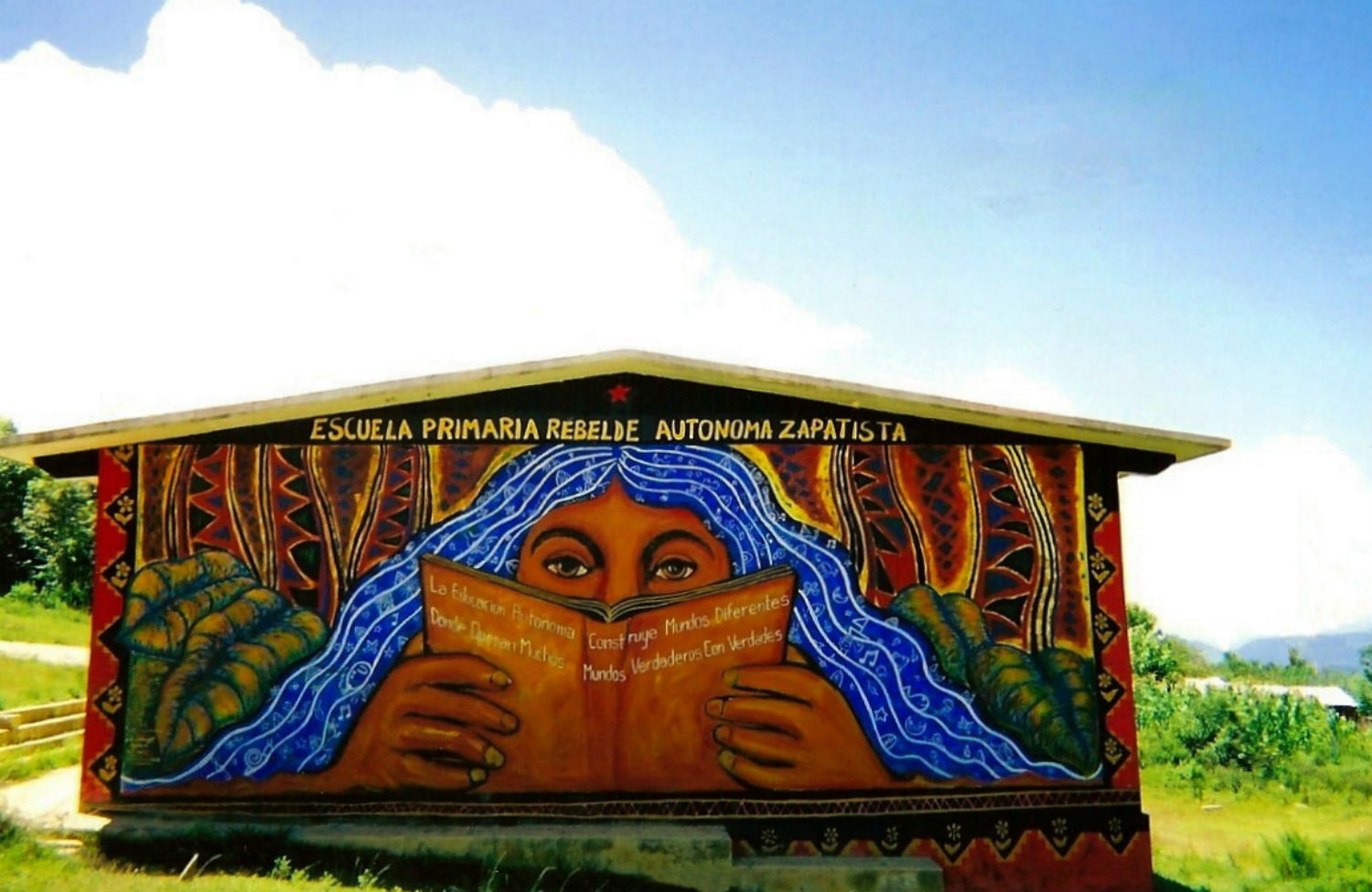

A primary school in the Zapatista village of Oventic in the southern state of Chiapas, Mexico. (Bastian/Flickr)

This article originally appeared at TomDispatch.com. To stay on top of important articles like these, sign up to receive the latest updates from TomDispatch.com.

Growing up in a well-heeled suburban community, I absorbed our society’s distaste for dissent long before I was old enough to grasp just what was being dismissed. My understanding of so many people and concepts was tainted by this environment and the education that went with it: Che Guevara and the Black Panthers and Oscar Wilde and Noam Chomsky and Venezuela and Malcolm X and the Service Employees International Union and so, so many more. All of this is why, until recently, I knew almost nothing about the Mexican Zapatista movement except that the excessive number of “a”s looked vaguely suspicious to me. It’s also why I felt compelled to travel thousands of miles to a Zapatista “organizing school” in the heart of the Lacandon jungle in southeastern Mexico to try to sort out just what I’d been missing all these years.

Hurtling South

The fog is so thick that the revelers arrive like ghosts. Out of the mist they appear: men sporting wide-brimmed Zapata hats, women encased in the shaggy sheepskin skirts that are still common in the remote villages of Mexico. And then there are the outsiders like myself with our North Face jackets and camera bags, eyes wide with adventure. (“It’s like the Mexican Woodstock!” exclaims a student from the northern city of Tijuana.) The hill is lined with little restaurants selling tamales and arroz con leche and pozol, a ground-corn drink that can rip a foreigner’s stomach to shreds. There is no alcohol in sight. Sipping coffee as sugary as Alabama sweet tea, I realize that tonight will be my first sober New Year’s Eve since December 31, 1999, when I climbed into bed with my parents to await the Y2K Millennium bug and mourned that the whole world was going to end before I had even kissed a boy.

Thousands are clustered in this muddy field to mark the twenty-year anniversary of January 1, 1994, when an army of impoverished farmers surged out of the jungle and launched the first post-modern revolution. Those forces, known as the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, were the armed wing of a much larger movement of indigenous peoples in the southeastern Mexican state of Chiapas, who were demanding full autonomy from their government and global liberation for all people.

As the news swept across that emerging communication system known as the Internet, the world momentarily held its breath. A popular uprising against government-backed globalization led by an all but forgotten people: it was an event that seemed unthinkable. The Berlin Wall had fallen. The market had triumphed. The treaties had been signed. And yet surging out of the jungles came a movement of people with no market value and the audacity to refuse to disappear.

Now, twenty years later, villagers and sympathetic outsiders are pouring into one of the Zapatistas’s political centers, known as Oventic, to celebrate the fact that their rebellion has not been wiped out by the wind and exiled from the memory of men.

The plane tickets from New York City to southern Mexico were so expensive that we traveled by land. We E-ZPassed down the eastern seaboard, ate catfish sandwiches in Louisiana, barreled past the refineries of Texas, and then crossed the border. We pulled into Mexico City during the pre-Christmas festivities. The streets were clogged with parents eating tamales and children swinging at piñatas. By daybreak the next morning, we were heading south again. Speed bumps scraped the bottom of our Volvo the entire way from Mexico City to Chiapas, where the Zapatistas control wide swaths of territory. The road skinned the car alive. Later I realized that those speed bumps were, in a way, the consequences of dissent—tiny traffic-controlling monuments to a culture far less resigned to following the rules.

“Up north,” I’d later tell Mexican friends, “we don’t have as many speed bumps, but neither do we have as much social resistance.”

After five days of driving, we reached La Universidad de la Tierra, a free Zapatista-run school in the touristy town of San Cristóbal de Las Casas in Chiapas. Most of the year, people from surrounding rural communities arrive here to learn trades like electrical wiring, artisanal crafts, and farming practices. This week, thousands of foreigners had traveled to the town to learn about something much more basic: autonomy.

Our first “class” was in the back of a covered pickup truck careening through the Lacandon jungle with orange trees in full bloom. As we passed, men and women raised peace signs in salute. Spray-painted road signs read (in translation): “You are now entering Zapatista territory. Here the people order and the government obeys.”

I grew nauseous from the exhaust and the dizzying mountain views, and after six hours in that pickup on this, my sixth day of travel, two things occurred to me: first, I realized that I had traveled “across” Chiapas in what was actually a giant circle; second, I began to suspect that there was no Zapatista organizing school at all, that the lesson I was supposed to absorb was simply that life is a matter of perpetual, cyclical motion. The movement’s main symbol, after all, is a snail’s shell.

Finally, though, we arrived in a village where the houses had thatched roofs and the children spoke only the pre-Hispanic language Ch’ol.

¡Ya Basta!

Over the centuries, the indigenous communities of Chiapas survived Spanish conquistadors, slavery, and plantation-style sugar cane fields; Mexican independence and mestizo landowners; racism, railroads, and neoliberal economic reforms. Each passing year seemed to bring more threats to its way of life. As the father of my host family explained to me, the community began to organize itself in the early 1990s because people felt that the government was slowly but surely exterminating them.

The government was chingando, he said, which translates roughly as deceiving, cheating, and otherwise screwing someone over. It was, he said, stealing their lands. It was extracting the region’s natural resources, forcing people from the countryside into the cities. It was disappearing the indigenous languages through its version of public education. It was signing free trade agreements that threatened to devastate the region’s corn market and the community’s main subsistence crop.

So on January 1, 1994, the day the North America Free Trade Agreement went into effect, some residents of this village—along with those from hundreds of other villages—seized control of major cities across the state and declared war on the Mexican government. Under the name of the Zapatista Army for National Liberation, they burned the army’s barracks and liberated the inmates in the prison at San Cristóbal de Las Casas.

In response, the Mexican army descended on Chiapas with such violence that the students of Mexico City rioted in the streets. In the end, the two sides sat down for peace talks that, to this day, have never been resolved.

The uprising itself lasted only twelve days; the response was a punishing decade of repression. First came the great betrayal. Mexican President Ernesto Zedillo, who, in the wake of the uprising, had promised to enact greater protections for indigenous peoples, instead sent thousands of troops into the Zapatistas’s territory in search of Subcomandante Marcos, the world-renowned spokesperson for the movement. They didn’t find him. But the operation marked the beginning of a hush-hush war against the communities that supported the Zapatistas. The army, police, and hired thugs burned homes and fields and wrecked small, communally owned businesses. Some local leaders disappeared. Others were imprisoned. In one region of Chiapas, the entire population was displaced for so long that the Red Cross set up a refugee camp for them. (In the end, the community rejected the Red Cross aid, in the same way that it also rejects all government aid.)

Since 1994, the movement has largely worked without arms. Villagers resisted government attacks and encroachments with road blockades, silent marches, and even, in one famous case, an aerial attack comprised entirely of paper airplanes.

The Boy Who Is Free

Fifteen years after the uprising, a child named Diego was born in Zapatista territory. He was the youngest member of the household where I was staying, and during my week with the family, he was always up to something. He agitated the chickens, peeked his head through the window to surprise his father at the breakfast table, and amused the family by telling me long stories in Ch’ol that I couldn’t possibly understand.

He also, unknowingly, defied the government’s claim that he does not exist.

Diego is part of the first generation of Zapatista children whose births are registered by one of the organization’s own civil judges. In the eyes of his father, he is one of the first fully independent human beings. He was born in Zapatista territory, attends a Zapatista school, lives on unregistered land, and his body is free of pesticides and genetically modified organisms. Adding to his autonomy is the fact that nothing about him—not his name, weight, eye color, or birth date—is officially registered with the Mexican government. His family does not receive a peso of government aid, nor does it pay a peso worth of taxes. Not even the name of Diego’s town appears on any official map.

By first-world standards, this autonomy comes at a steep price: some serious poverty. Diego’s home has electricity but no running water or indoor plumbing. The outhouse is a hole in the ground concealed by waist-high tarp walls. The bathtub is the small stream in the backyard. Their chickens often free-range it right through their one-room, dirt-floor house. Eating them is considered a luxury.

The population of the town is split between Zapatistas and government loyalists, whom the Zapatistas call “priistas” in reference to Mexico’s ruling political party, the PRI. To discern who is who, all you have to do is check whether or not a family’s roof sports a satellite dish.

Then again, the Zapatistas aren’t focused on accumulating wealth, but on living with dignity. Most of the movement’s work over the last two decades has involved patiently building autonomous structures for Diego and his generation. Today, children like him grow up in a community with its own Zapatista schools; communal businesses; banks; hospitals; clinics; judicial processes; birth, death, and marriage certificates; annual censuses; transportation systems; sports teams; musical bands; art collectives; and a three-tiered system of government. There are no prisons. Students learn both Spanish and their own indigenous language in school. An operation in the autonomous hospital can cost one-tenth that in an official hospital. Members of the Zapatista government, elected through town assemblies, serve without receiving any monetary compensation.

Economic independence is considered the cornerstone of autonomy—especially for a movement that opposes the dominant global model of neoliberal capitalism. In Diego’s town, the Zapatista families have organized a handful of small collectives: a pig-raising operation, a bakery, a shared field for farming, and a chicken coop. The twenty-odd chickens had all been sold just before Christmas, so the coop was empty when we visited. The three women who ran the collective explained, somewhat bashfully, that they would soon purchase more chicks to raise.

As they spoke in the outdoor chicken coop, there were squealing noises beneath a nearby table. A tangled cluster of four newly born puppies, eyes still crusted shut against the light, were squirming to stay warm. Their mother was nowhere in sight, and the whole world was new and cold, and everything was unknown. I watched them for a moment and thought about how, although it seemed impossible, they would undoubtedly survive and grow.

Unlike Diego, the majority of young children on the planet today are born into densely packed cities without access to land, animals, crops, or almost any of the natural resources that are required to sustain human life. Instead, we city dwellers often need a ridiculous amount of money simply to meet our basic needs. My first apartment in New York City, a studio smaller than my host family’s thatched-roof house, cost more per month than the family has likely spent in Diego’s entire lifetime.

As a result, many wonder if the example of the Zapatistas has anything to offer an urbanized planet in search of change. Then again, this movement resisted defeat by the military of a modern state and built its own school, medical, and governmental systems for the next generation without even having the convenience of running water. So perhaps a more appropriate question is: What’s the rest of the world waiting for?

Celebrating Dissent

Around six o’clock, when night falls in Oventic, the music for the celebration begins. On stage, a band of guitar-strumming men wear hats that look like lampshades with brightly colored tassels. Younger boys perform Spanish rap. Women, probably from the nearby state of Veracruz, play son jarocho, a type of folk music featuring miniature guitar-like instruments.

It’s raining gently in the open field. The mist clings to shawls and skirts and pasamontañas, the face-covering ski masks that have become iconic imagery for the Zapatistas. “We cover our faces so that you can see us” is a famous Zapatista saying. And it’s true: for a group of people often erased by politicians and exploited by global economies, the ski-masks have the curious effect of making previously invisible faces visible.

Still, there are many strategies to make dissent disappear, of which the least effective may be violence. The most ingenious is undoubtedly to make the rest of the world—and even the dissenter herself—dismissive of what’s being accomplished. Since curtailing its military offensive, the government has waged a propaganda war focused on convincing the rest of Mexico, the world, and even Zapatista communities themselves that the movement and its vision no longer exists.

But there are just as many strategies for keeping dissent and dissenters going. One way is certainly to invite thousands of outsiders to visit your communities and see firsthand that they are real, that in every way that matters they are thriving, and that they have something to teach the rest of us. As Diego’s father said in an uncharacteristic moment of boastfulness, “I think by now that the whole world has heard of our organization.”

Writing is another way to prevent an idea and a movement from disappearing, especially when one is hurtling down the highway in Texas headed back to New York City, already surrounded by a reality so different as to instantly make the Zapatistas hard to remember.

The most joyous way to assert one’s existence, however, is through celebration.

The New Year arrived early in Oventic. One of the subcomandantes had just read a communique issued by the organization’s leadership, first in Spanish, then in the indigenous languages Tzotzil and Tzeltal. The latter translations took her nearly twice as long to deliver, as if to remind us of all the knowledge that was lost with the imposition of a colonial language centuries ago. Then, a low hiss like a cracked soda can, and two fireworks exploded into the air.

“Long live the insurgents!” a masked man on stage cried.

“Viva!” we shouted. The band burst into song, and two more fireworks shot into the sky, their explosions well timed drumbeats of color and sound. The coordination was impeccable. As the chants continued, the air grew so smoky that we could barely see the fireworks exploding, but in that moment, I could still feel their brilliance and the illumination, twenty years old, of the movement releasing them.

Laura GottesdienerLaura Gottesdiener is a correspondent for Reuters based in Mexico. She reported all of her pieces for The Nation before joining Reuters.