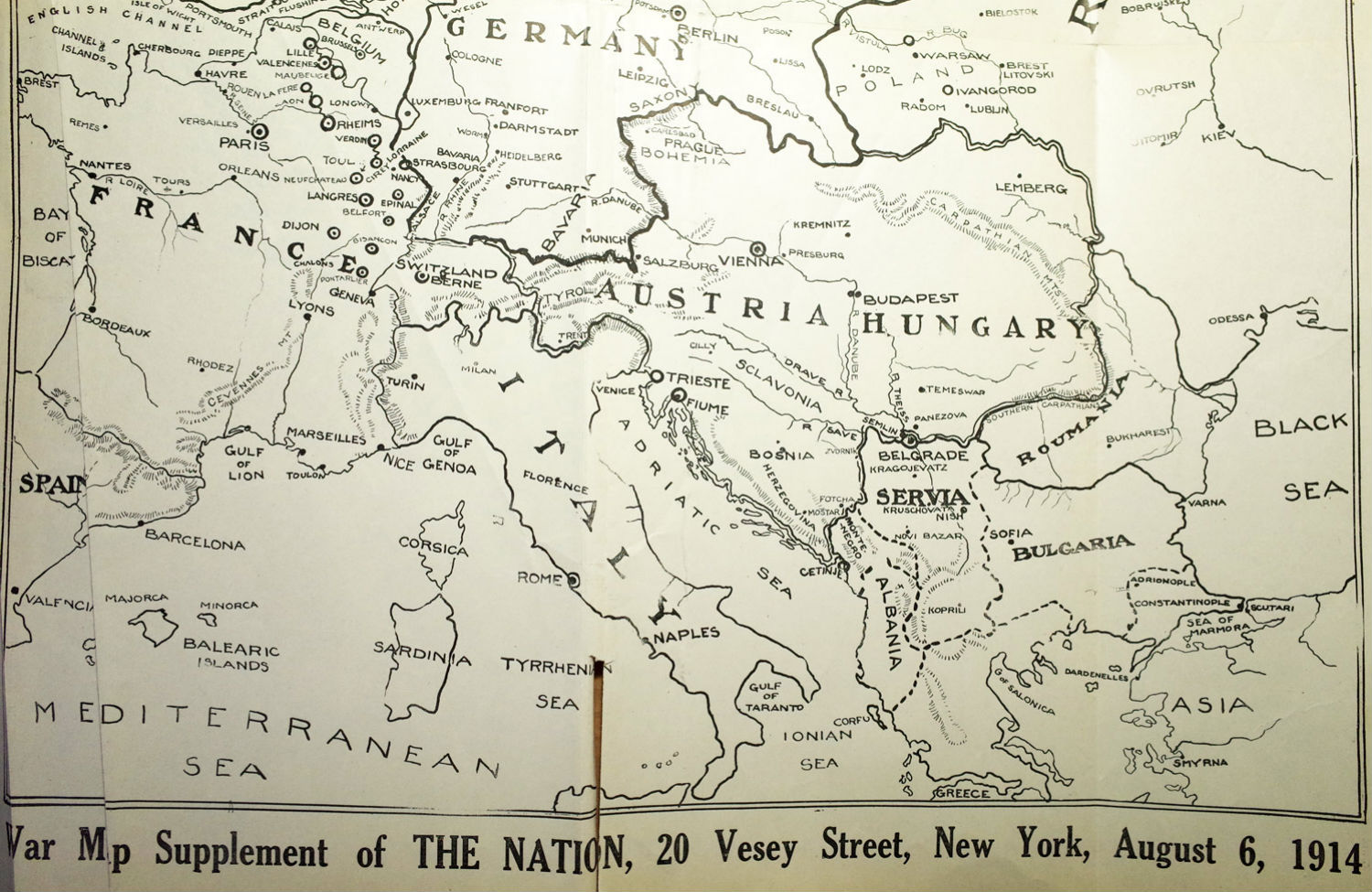

To read contemporaneous accounts of the beginning of World War I is to witness the disintegration of a world. The July 23 issue of The Nation doesn’t mention the European situation at all. The July 30 issue, apparently published just after the Austrian declaration of war against Serbia on July 28, observed that the entire continent seemed to be going mad all at once. Then a week later, Nation readers picking up the August 6 issue would have noticed a surprising bulge in the middle of the magazine: a massive four-page fold-out map of Europe in the first week of the Great War.

The first item in the Summary of the News in the issue expressed hope “for a speedy termination of the conflict and for a final settlement that may make it impossible for those few men who have brought about this calamity ever again to decide for nations the issues of life and death.” The magazine wished, that is, that if there had to be a war, it should be a war to end all wars.

After relating the timeline of the July crisis in all its unfortunate details, the editors reflected on the implications for the United States. Most remarkable is the complete absence of any suggestion that there would even become a debate about whether the Americans should get involved; the world of August 1914 was such that that contingency wasn’t even worth entertaining. In an item about the financial consequences, American isolation was taken for granted:

The part which the people at large will be called upon to play is to accept philosophically such temporary inconvenience as Europe’s troubles may occasion in their banking arrangements, and to recognize the great underlying strength and soundness of the American position. We shall presently learn what it really means to be a self-supporting industrial, agricultural, and commercial state, at a time when the rest of the world is going to war, and when the fighting nations must depend for their subsistence on the supplies of foodstuff which we are better able than ever before in our history to spare for them.

In its editorials section, the magazine laid the blame for war squarely upon Germany. “Her entrance into Luxembourg, her invasion of Belgium,” Rollo Ogden, editor of The Nation’s parent publication, The New York Evening-Post, wrote, “were the directest kind of challenge to England, and there was never any doubt as to how it would be answered. By this action Germany has shown herself ready to lift an outlaw hand against the whole of Western Europe…. By the light we have at present, this at least is clear, that if Emperor Willliam did not directly cause and desire the war, he at least failed to prevent it when it would have been easy for him to do so.”

That choice, Ogden continued, “was a decision big with fate.” His concluding paragraph is remarkably prescient:

The human mind cannot yet begin to grasp the consequences. One of them, however, seems plainly written in the book of the future. It is that, after this most awful and most wicked of all wars is over, the power of life and death over millions of men, the right to decree the ruin of industry and commerce and finance, with untold human misery stalking through the land like a plague, will be taken away from three men. No safe prediction of actual results of battle can be made. Dynasties may crumble before all is done; empires change their form of government. But whatever happens, Europe—humanity—will not settle back again into a position enabling three Emperors—one of them senile, another subject to melancholia, and the third often showing signs of disturbed mental balance—to give, on their individual choice or whim, the signal for destruction and massacre.

The senile monarch Ogden refers to is clearly the aged Franz Josef of Austria-Hungary, for whose health The Nation had already expressed concern after the assassinate of his nephew, Franz Ferdinand. As far as I know, Wilhelm of Germany was alternately melancholic and erratic. I do not know enough about the Tsar to confirm which epithet referred to him—knowledgeable readers please inform us in the comments below. More importantly, though, Ogden was correct in predicting the three would lose their power to wage war: their empires, not only their dynasties, lay crumpled and discarded by the end of the war.

The next article was by Oswald Garrison Villard, the pacifist owner of both The Nation and the Post, who began his career as a military journalist. “Forecasts as to what may happen,” Villard wrote, “now that all Europe has decided to halt the progress of civilization by going in for wholesale murder on a more terrible scale than the world has yet witnessed, would be utterly futile. The magnitude of the forces involved staggers the imagination.” The entry of Britain, he concluded with a somewhat histrionic, if appropriate, air, “makes inevitable the greatest battles the world has yet seen, to make a mock of our Christianity, 1,900 years after the coming of the Prince of Peace.”

Back Issues is following this magazine’s coverage of the “Great War”—in real time, a century later.

Curious about how we covered something? E-mail me at rkreitner@thenation.com. Subscribers to The Nation can access our fully searchable digital archive, which contains thousands of historic articles, essays and reviews, letters to the editor and editorials dating back to July 6, 1865.

Richard KreitnerTwitterRichard Kreitner is a contributing writer and the author of Break It Up: Secession, Division, and the Secret History of America's Imperfect Union. His writings are at richardkreitner.com.

Back IssuesGuided tours through the archive of America’s oldest weekly.