“Everyone knows who Hong Sang-soo is nowadays,” my mother told me recently over the phone. “Yes, because of the scandal.” A few years ago, his name was all over South Korean gossip sites, but before that, Hong was only a subject of interest for dedicated cinephiles, even in his own country. He had quietly built a reputation as South Korea’s great auteur.

Since debuting in 1996, Hong has used his films to probe the darker sides of modern romance. Shot using long takes and zooms that may seem innocuous or lazy, his cinematography reflects the wandering eyes of his characters and Hong’s own attention to detail. His films have been called too talky, too heady, maddingly recursive, and confusing—especially since many are rendered dreamlike by time jumps, narrative shifts, and deus ex machina—but Hong’s catalog reflects that of a filmmaker working through his ideas: of love and all the regrets, what if’s, and do-overs that come with it.

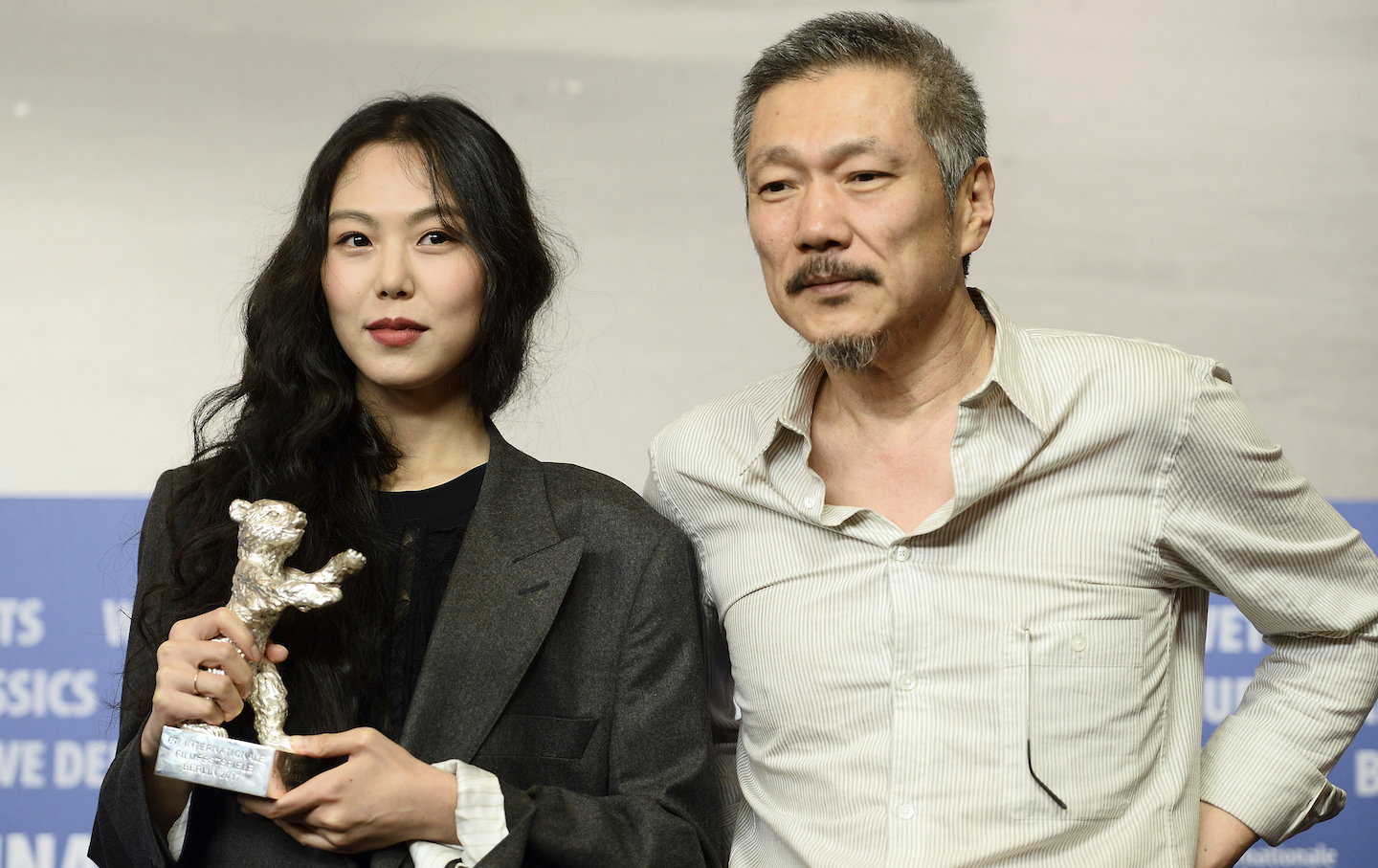

Hong has never enjoyed huge box-office success—at home or internationally—but he has, in recent years, become a fixture at Cannes, Venice, Berlin, and Locarno. His recent rise in recognition in his home country, though, has less to do with critical acclaim and more to do with his personal life. In 2016, the filmmaker, then 55, was embroiled in a very public scandal over an extramarital affair with 34-year-old actress Kim Min-hee. Hong’s wife was reluctant to divorce him, and websites even published alleged text exchanges between the two women. Affairs—and public knowledge of them—may be more commonplace in Hollywood, but adultery was illegal in South Korea until 2015, an exacerbating factor in this real-life drama. What’s more, Hong seemed to be confessing his infidelity over and over again through his films.

Hong’s films have focused on drunken mistakes and affairs—often between people who work in the movie industry—for years, but only recently have their characters seemed like surrogates for the director himself.

Since 2015’s Right Now, Wrong Then, Kim has starred in every single Hong film (a total of six films in less than four years), with the exception of 2016’s Yourself and Yours. In most of them, Kim becomes the center of an awkward romantic situation—by drunken pursuit or misjudgment. In many of them, Kim’s professional life becomes threatened because of her love life, too.

Hong’s recent film Hotel by the River employs many of the aforementioned elements, but without pitting Kim against another slurring lover. In fact, for the first time her love interest (or assumed love interest) does not appear on the screen. The film marks a new point of maturity and eschews the kind of biographical subtext that has fanned the flames of Hong and Kim’s affair. It is about two different, unrelated parties staying at a hotel—one, an aging poet, whose two adult sons visit him; and the second, a heartbroken woman, whose friend comes to comfort her. Through these orbiting parties, Hong plots comedic run-ins and mistimings to look back on life from a more ruminative, even existential perspective. This hotel, a hideout of sorts for both the poet and the woman, feels removed from the real world; simultaneously, it feels removed from the real-life drama that has hampered Hong and Kim’s artistic partnership.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Prior to Hotel by the River, Hong’s films were defined by metanarratives that invited scrutinized, subtextual analysis. Right Now, Wrong Then, Hong’s first collaboration with Kim, told an uncannily familiar story of a woman who becomes romantically entangled with a film director. Though Hong will be the last to admit the autobiographical nature of his work, his exploration of the thorny intricacies of romance and creativity has a knowing intimacy that almost implicates the viewer.

Similarly, in Hong’s 2017 On the Beach at Night Alone, Kim plays Young-hee, an out-of-work actress still spiraling from an affair with a filmmaker. By the end of the film, the two are reunited, and the director tells her he’s making a film about a person he loved. In a soju-fueled explosion, Young-hee screams back, “Why make it about someone you loved? Trying to lessen your torment?” The director responds, “I need to cast off my regrets.” At the film’s conclusion, Young-hee wakes up on the beach, and no resolution has been met—the entire argument happened in a dream. Hong plays with our expectations, but instead gives us the fantasy of that confrontation, saying everything you ever wanted to say to an ex-lover.

Of course, the film is not explicitly—or even accurately—about Hong and Kim, but the cathartic yelling between two lovers feels therapeutic. Hong uncomfortably and faithfully renders relationships that carry history—it’s this astuteness that has earned him many a comparison to the French New Wave director Éric Rohmer. The similarity has been noted since the early days of Hong’s career, but it feels especially accurate now, with his newfound interest in religion, a theme common to Rohmer’s work. There is a confessional nature to Hong’s recent films that seems to strive for absolution through spiritual means—in On the Beach, Kim’s character often prays; in Hong’s other 2017 release, The Day After, she initiates a conversation about God with her boss. In all of her roles, Kim toes the line between sinner and saint with a distinctly messy and human quality; she gives in to her desires yet is martyred for them.

Kim plays characters who aren’t necessarily faultless, but they often suffer due to misinterpretations from the men around them. These films are apologetic on Kim’s behalf, but they hardly absolve men of their lurid, bumbling mistakes. But Kim’s captivating screen presence has also provided the charisma to flesh out both comedic mishaps and the inner turmoil of a contemporary single woman. Hong always manages to find something funny in these sticky situations.

Hong’s comedy can be dark and self-deprecating, often mined from awkward group settings—for example, a man says he feels left out when everyone pairs off and starts drunkenly kissing each other at a restaurant. Kim wasn’t the one to introduce comedy to Hong’s filmography, but the way her performances mix naivety and sensuality works well with Hong’s humor, even when she’s just a witness to men working out their feelings.

That’s where Kim finds herself in Hotel by the River. Kim’s character is at a restaurant with her friend, eavesdropping on an older father and his two adult sons sitting just a table away. With the increasing consumption of soju and makgeolli (rice wine), the men raise their voices—it’s another alcohol-bolstered argument, but this time not between scorned lovers. The father chastises his younger son for being afraid of women and stunting his love life. The older son explains that it’s because of their mother that he turned out this way, and the younger son drunkenly screams back at his father for abandoning him and his brother when they were children. “You can’t live your life based on guilt,” the father responds. “People need to follow real love.” It sounds like a line Hong has used before—but here, Kim becomes spectator rather than participant; the finger-pointing is pushed away from her altogether.

This film premiered last year, as did its unofficial companion piece, the 66-minute Grass (out now in limited release), another Hong and Kim collaboration; in both, Kim finds herself as an eavesdropper. The love affairs with film directors are also over. In Hotel by the River, her character is slowly recovering from a breakup—and though one of the main characters is a director, he surprisingly isn’t the one she was involved with. She’s rarely given male companionship in the film; instead, her female friend visits her at the hotel where she’s been staying to nurse not only her broken heart, but also her hand, burned from unexplained circumstances.

Hotel by the River feels like a new shift in Hong’s filmography, despite familiar images and themes from his past films—drunken disputes, filmmaker characters. He’s employed handheld camerawork (unusual, considering his preference for tripods), turning viewers into active, breathing witnesses and contemplators of their own lives. We become as much participants as Kim; Kim becomes as much of a spectator as the audience. More than in previous films, it becomes easiest to empathize with the role of Kim, and thus the playing field becomes even.

There is also a newfound meditation of death that’s a departure from his first few films. There is something resigned and peaceful here—a late-career acceptance of mortality. Perhaps it’s Hong’s recent fascination with spirituality that’s made its way into On the Beach at Night Alone and The Day After, and now again, in Hotel by the River, as the fading poet explains to his younger son that his name, Byung-soo, has a heavenly implication. If Hong is still “casting off his regrets,” these regrets feel more existential; he no longer feels like a filmmaker thwarting sensationalized headlines. He’s said that the focus on religious themes counteracts some of the darker, nihilistic elements of his earlier films. Even with all the interpersonal pettiness, secrets, and lies, the wistful Hotel by the River feels like the work of a filmmaker no longer bogged down by earthly concerns.