A new initiative aims to put wages at the heart of the inequality debate.

Zoë Carpenter

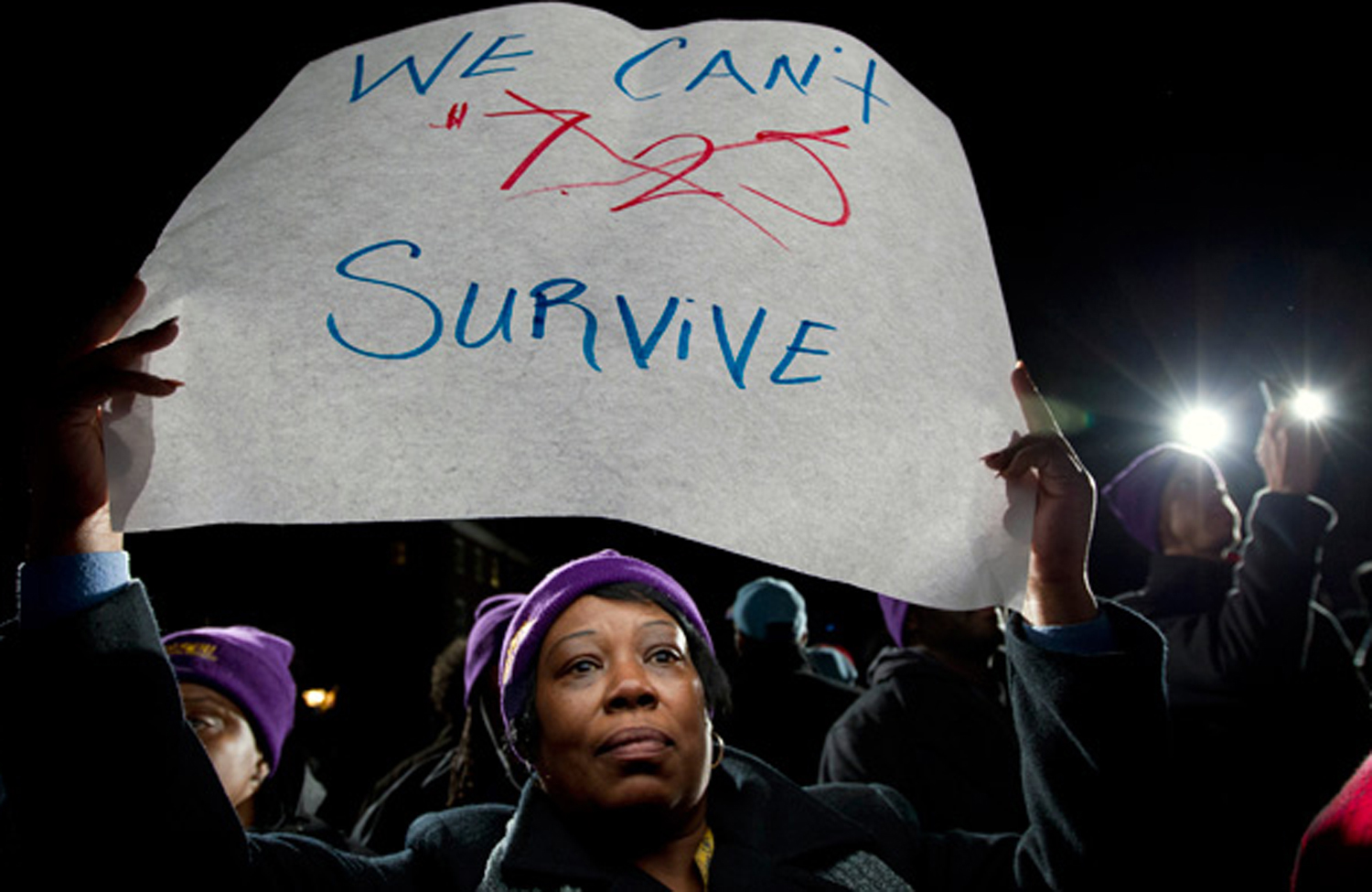

(AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana)

What can be done to reverse rising economic inequality in America—not just for future generations, but right now?

Raise wages. That’s the conclusion of a new policy report from the Economic Policy Institute and the starting point for a multi-year research and education initiative that was launched on Wednesday with a keynote address by Secretary of Labor Thomas Perez. The paper’s central argument is that the root of America’s most pressing economic challenges lies in the disconnect between wages and productivity—and that government policy and business practices are in large part to blame.

“The clear connections between wages, income and living standards mean that progress in reversing inequality, boosting living standards and alleviating poverty will be extraordinarily difficult without addressing wage growth,” reads the introduction to the report, which was written by EPI President Lawrence Mishel and economists Josh Bivens, Elise Gould and Heidi Shierholz. “Indeed, converting the slow and unequal wage growth of the last three-and-a-half decades into broad-based wage growth is the core economic challenge of our time.”

According to EPI, wages for the entire bottom 70 percent of earners have been falling since 2002. The minimum wage is now 25 percent lower than its peak in 1968. Racial disparities in hourly wages for white, black and Hispanic workers have not narrowed with time. Most Americans depend on work-based income to pay their bills (rather than tax credits, pensions or social insurance), so these wage trends directly impact college graduates and high school dropouts alike. Even the bottom fifth of American households rely on earnings from work for more than two-thirds of their total income—meaning that stagnant wages have played a large role in keeping families poor.

As Perez put it, “Workers are getting a smaller share of the pie that they helped to bake.” The burden isn’t born only by workers: the whole economy suffers, Perez argued, when people don’t have money to spend.

Counterintuitively, the authors of the report say their data points to empowering conclusions. “The American people now are in an economic fetal position,” Mishel said in an interview. “But we argue that there is no deity or economic forces beyond our control that have put us in the position we are. We, through democratic means, can make it different.”

So what put American workers into the fetal position? One of the initiative’s goals is to provide an alternate narrative to the one that chalks up low wages to globalization and technological change. More important, according to EPI, are the cumulative effects of exploitative business practices like wage theft, the misclassification of employees as subcontractors, and keeping workers below the full-time threshold, along with successful attacks on labor rights, and a high unemployment rate, which makes workers easily replaceable and gives employers little incentive to raise wages. Other factors include the low minimum wage and a broken immigration system that renders undocumented workers vulnerable to abuse while robbing other legal immigrants of bargaining power by tying their visas to their employer.

“A whole universe of labor standards and institutions has been allowed to erode away or affirmatively kicked away,” said Bivens. “Maybe any single one of them would not reverse inequality, but the accretion of them over time could have a real effect.”

The essential point here is that what’s keeping wages low for the majority of Americans are deliberate policy decisions. One example is the minimum wage; because of inflation, not raising the wage floor is effectively choosing to lower it. The happy corollary is that targeting the practices and policies keeping wages low gives lawmakers a variety of tools with which to combat inequality—if only they had the will to use them.

Campaigns for a higher minimum wage have garnered the most attention of late, but other measures are on the table, too. Last fall, for example, Democratic Senator Bob Casey introduced a bill to crack down on the misclassification of independent contractors. The Obama administration is reconsidering the rules governing who is eligible for overtime pay. Currently, the salary threshold is set around $24,000, meaning anyone with a higher salary is not guaranteed overtime pay. Sixty-five percent of American workers were guaranteed overtime in 1973. Now as few as 12 percent can count on “time and a half” pay for their extra labor.

Mishel acknowledged that putting wages first wouldn’t seem radical at any dining room table in America. But in Washington the discussion of inequality often skirts the issue of pay and labor standards, focusing instead on access to education and training, or on expanding the social safety net for the poorest.

“When the conversation goes from income inequality to pre-K—I mean, that’s fine, but that’s really talking about social mobility for the next generation. That’s different than the conversation that we think needs to be had, which is: How are we going to get income growth and shared prosperity for people within the next five, ten years?” said Mishel. Nor is expanding the safety net a sufficient counterbalance to wage stagnation, he said. “If wages at the bottom keep going down, are we going to make the tax and transfer system bigger every year?”

Some of the reluctance to put wages at the center of an anti-inequality agenda comes from politicians who “say they don’t want to mess with the market forces,” said Gould. “But the system is already rigged.” She continued, “There is a systematic effort, really, to dismantle a lot of the policies that protected workers.”

That effort, led by conservative politicians armed with anti-worker, union-busting legislation from the American Legislative Exchange, may be the best indicator of how significant labor market practices and policies really are. “Employers obviously think it matters,” Bivens said. “They spend a lot of money to lobby governments to change it in their favor.”

Zoë CarpenterTwitterZoë Carpenter is a contributing writer for The Nation.