The United States has a voter-turnout problem. For decades, participation in presidential elections has ranged from about 50 to 65 percent of eligible voters, and in midterm elections has averaged between 25 and 45 percent. Turnout in state and local elections is typically much lower, sometimes in the single digits. Voter turnout in the United States trails that of most other developed democracies.

Low voter turnout is not merely a problem of numbers. It has the effect of skewing politics and policy making toward the preferences of groups most likely to turn out to vote: whites, older Americans, the affluent, and those with more education. Conversely, people of color, low-income people, and young people are substantially underrepresented in the electoral process and in policy making. Instead of giving everyone an equal voice in the political process, our democracy gives some people voice and power, while others are shut out—including many who have historically faced, and continue to face, active suppression of their right to vote.

For this reason, activists, policy-makers, and social scientists have worked for decades to increase turnout in elections. Reforms that target registration tend to be most effective. For instance, same-day registration boosts participation and facilitates stronger class diversity among the electorate. But even then, it is a persistent challenge to maintain and expand overall participation, particularly among people who vote less consistently.

Recently, policy-makers have begun examining automatic voter registration (AVR). It has generated a lot of excitement, and rightly so. New research from Demos examines the effects of Oregon’s recent adoption of AVR on the level and composition of turnout in the 2016 federal election. Using unique individual-level data, we provide new evidence that AVR increased the racial diversity of Oregon’s electorate. Our findings suggest that AVR is effective in raising voter turnout, especially among individuals who are voting for the first time or are less-frequent voters. These patterns point to a positive relationship between AVR and increased voter participation, and demonstrates that AVR is a successful reform to reduce political inequities stemming from the historic underrepresentation of young people, people of color, and low-income people in the electorate.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Oregon’s AVR Program

In almost every state, persons who wished to vote in the 2016 election had to take affirmative steps to register themselves. This system of self-registration puts the burden on the individual to obtain and maintain registration status.

The exceptions were North Dakota (which does not legally mandate registration in order to vote) and Oregon, which in January 2016 became the first state in the country to implement automatic voter registration. This reform increased access to voting by using information already provided to the government in order to add eligible individuals onto the voter rolls. Under the new Oregon program, eligible voters who have a qualifying interaction with the DMV are notified by mail that they will be added to the voter rolls, unless they decline registration or opt out within 21 days by returning a postcard to the state’s election authorities. For purposes of primary voting, this notification postcard also allows individuals to choose a political party. If no response is given, these individuals become automatically registered as “non-affiliated” voters, which makes them ineligible to vote in primaries because Oregon has a closed primary system. Automatic address updates and notifications also take place through this system.

AVR Helped Increase Turnout and Promote A More Inclusive Electorate

In 2016, 288,516 people registered to vote for the first time in Oregon. Of individuals registering for the first time, 186,050—or 66 percent—were registered via the AVR program. An additional 35,000 Oregon residents whose registration had lapsed were reregistered through AVR. Given these figures, it is not unreasonable to conclude that without AVR, 220,000 fewer citizens likely would have had the opportunity to vote in the 2016 elections.

Did people registered by AVR turn out to vote? Of the individuals who were registered for the first time through Oregon’s new program, a significant portion—67,902, or 36 percent—voted in 2016. In our view, AVR has been successful in mobilizing many new Oregonians to participate in the election who may not have voted without this program being in place.

Critics will find difficulty arguing against the Oregon AVR’s healthy turnout impacts. Turnout in Oregon increased more between 2012 and 2016 than in any other state. Overall voter turnout in the state reached 68 percent in the 2016 presidential election, up from 64 percent during the 2012 non-AVR election period. Nationally, voter turnout increased by only 1.6 points. This stands out for two reasons. First, Oregon already held perennial status as one of the top voter-participation states in the country. Second, in a non-swing state that didn’t feature a competitive Senate race, the 2016 presidential candidates invested zero television or radio advertisement dollars during the critical final two-and-a-half weeks leading up to Election Day. We estimate that AVR accounted for at least 38 percent of individuals who registered in 2016 and voted.

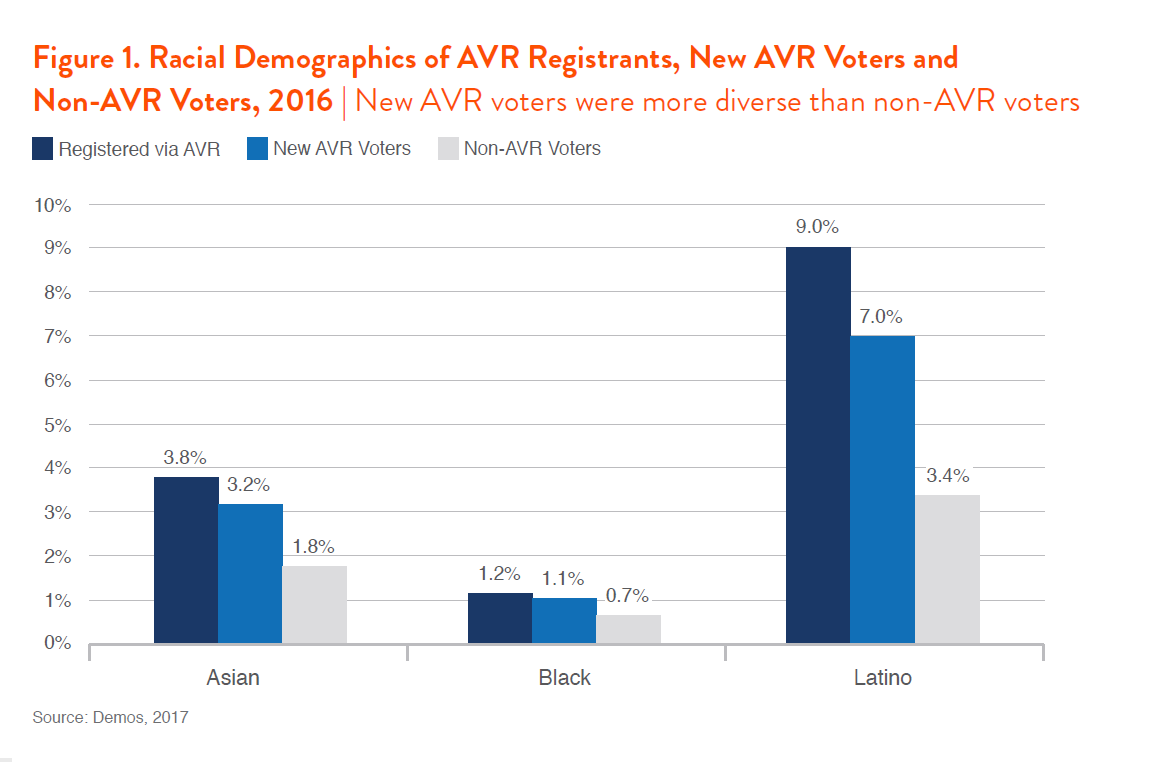

AVR also helped increase the diversity of Oregon’s electorate. Oregon’s citizen voting-age population is 84 percent white, but its voting electorate is 94 percent white. By comparison, 89 percent of the new AVR voters (individuals who were registered using AVR and had no record of voting going back to 2008) were white. Fourteen percent of those who were registered automatically were people of color, roughly equal to the share of the Oregon’s minority population (16 percent). While 3 percent of non-AVR voters were Latino, 7 percent of new AVR voters and 9 percent of AVR registrants were. Less than 2 percent of the non-AVR voters were Asian, compared to 4 percent of AVR registrants and 3 percent of AVR voters.

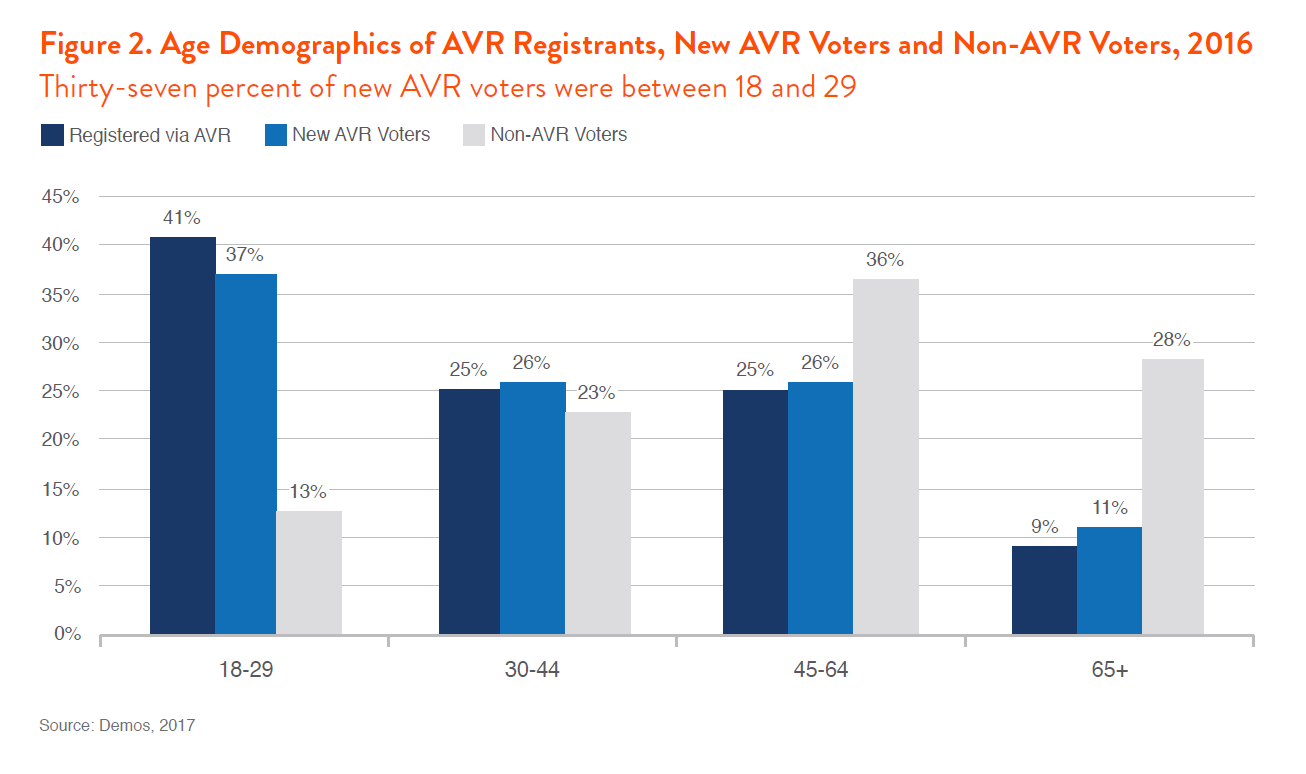

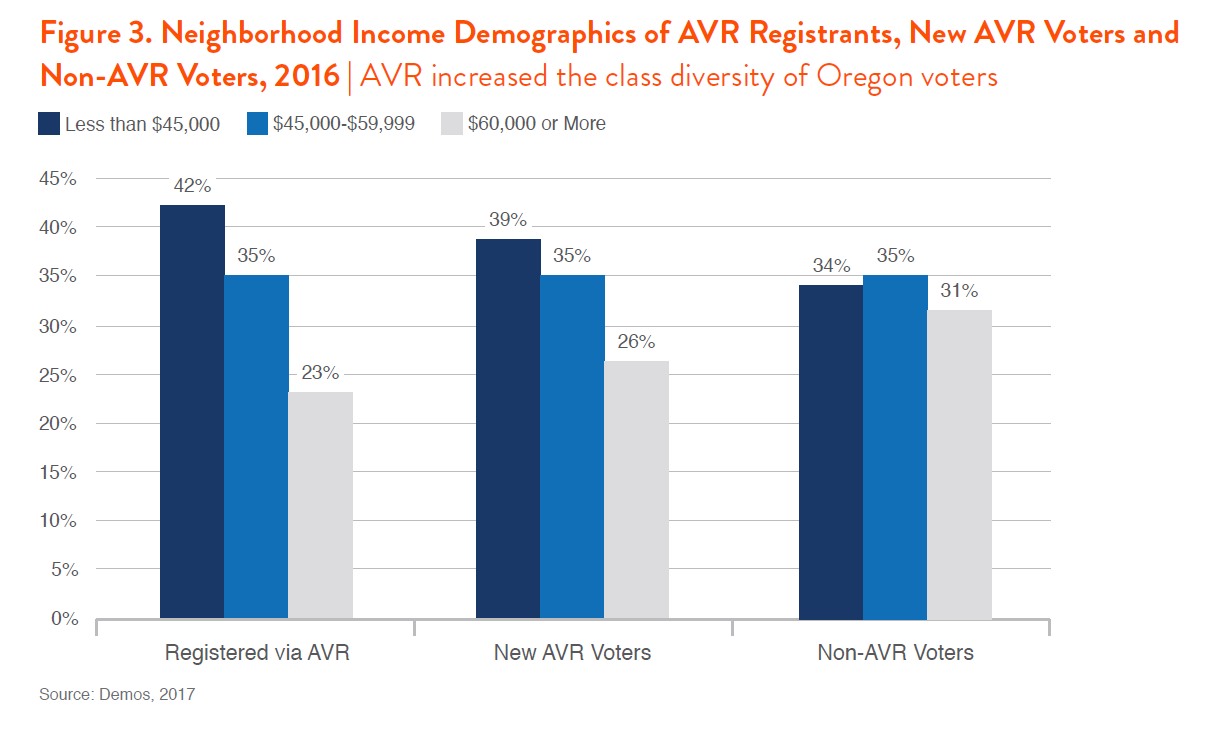

AVR also brought in more young and low-income voters. Only 13 percent of non-AVR voters were between the ages of 18 and 29, compared to 37 percent of new AVR voters. And 39 percent of new AVR voters lived in Census Blocks with a median income below $45,000 compared to 34 percent of non-AVR voters. Twenty-six percent of new AVR voters lived in neighborhoods with a median income over $60,000, compared with 31 percent of non-AVR voters.

A Key Reform for Democratic Inclusion

The Oregon program has important implications for both the extent and composition of voter turnout. The causes of low voter turnout in the United States are clear: The requirement that individuals register in order to become eligible to vote is a major obstacle to equal participation in American elections. Many nations with higher turnout rates automatically enroll their citizens to vote.

Some academics and policy-makers scoff that if people want to vote, they will register ahead of time. However, many states have registration deadlines as far out as 30 days before an election. This unduly punishes individuals who may want to register but can’t because of practical life realities—such as losing time from work, caregiving responsibilities, or transportation access, among other reasons—which render these deadlines prohibitive. Research suggests that deadlines closer to the election increase turnout, and extensive research confirms that same-day registration also bolsters participation.

Automatic voter registration could empower workers with multiple jobs, low-income people, people of color, and young people to fully participate in our democracy. Our evidence suggests that automatic registration increases turnout and the diversity of the electorate. It’s time for more states to embrace this important idea for a more robust and inclusive democracy.