Glenn Greenwald’s No Place to Hide chronicles the publication of secret NSA files that reshaped global conversations about government surveillance.

Betty Medsger

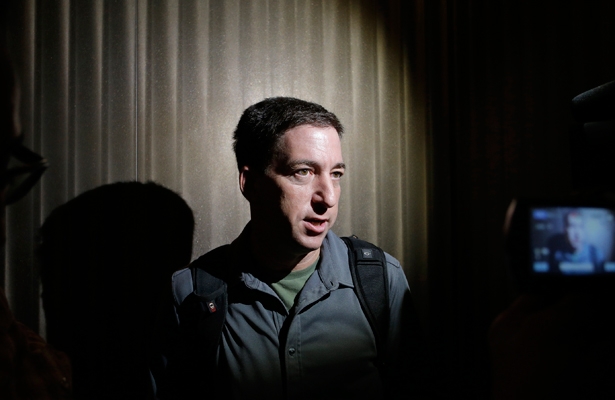

Glenn Greenwald speaks to reporters in Hong Kong, June 10, 2013. (AP Photo/Vincent Yu)

For several months journalist Glenn Greenwald ignored the efforts of Cincinnatus, an anonymous source who later identified himself as Edward Snowden, to give him information he promised would be of interest. Greenwald thought he was just another nut with a “big” story, the kind that seldom pans out. The aspiring source also irritated Greenwald by instructing him to install encryption software so they could communicate securely. Forget it. Greenwald was a busy guy and didn’t have time for such complications.

Fortunately, documentary film maker Laura Poitras, also contacted by Snowden, pushed Greenwald to respond to the source. After meeting with Snowden last June in Hong Kong, Greenwald and Poitras, along with Guardian reporter Ewen MacAskill, began reporting on what the world now knows as the Snowden files—the thousands of files that continue to inform Americans and people throughout the world that since 9/11 the National Security Agency has turned the Internet and all forms of electronic communication, even video games, into a vast spying machine.

Greenwald’s new book, No Place to Hide, reports the full story of what has flowed from private NSA contractor Snowden’s decision to sacrifice his freedom and, if necessary, his life in order to collect and hand over to journalists a massive archive of files he thought the public needed access to: evidence of the NSA’s use of massive surveillance to spy on Americans without regard to suspicion of crime, to influence foreign policy, to conduct industrial and economic espionage and to develop new cyber warfare capacities.

As the revelations poured into the public domain, it become clear that congressional intelligence oversight committees—established in the mid-1970s after the exposure of secret FBI files led to the first congressional investigations of intelligence agencies—had lost their adversarial function and become largely cheerleaders for the agencies. Telecommunication companies, the files revealed, are partners in the massive surveillance and readily supply records of the calls of all of their customers.

It is staggering to review the importance of the Snowden files released so far, including a report that explains that “collect it all,” the motto of General Keith B. Alexander, director of the NSA, is not a joke about grandeur; it is the actual goal that has governed expanding operations in pace with the ever-increasing capacity of data-gathering technology rather than in line with what technical prowess is actually needed in order to improve national security. One NSA file documented the staggering volume collected was “far more content than is routinely useful to analysts.” The agency, according to another file, processes more than 20 billion communication events (Internet and telephone) from around the world every day.

In Greenwald’s account of the remarkable year he has been at the helm of the reporting of one startling intelligence revelation after another, he strongly criticizes mainstream news media for being what he sees as primarily protectors of the government’s secrets:

US establishment journalism…is wholly integrated into the nation’s dominant political power…. They are one and the same. …Insider journalists do not want to subvert the status quo that so lavishly rewards them. Like all courtiers, they are eager to defend the system that vests them with their privileges and contemptuous of anyone who challenges that system.

Like Greenwald’s sometimes sledgehammer analysis of mainstream journalism, reports about him, as well as about Snowden, also were extremely harsh. Though Greenwald reported the files in a straightforward way, some journalists described him as an activist, as someone who expressed opinion. It was a description that seemed calculated to suggest his reporting should not be taken seriously. (Since 2001 he had been writing a political blog; he later wrote for Salon and had been a columnist since 2011 at The Guardian. In early 2014, Greenwald, Poitras and Jeremy Scahill became editors of The Intercept, the new journalism website funded by eBay founder Pierre Omidyar.)

On CNN, Alan Dershowitz said of Greenwald’s reporting on the Snowden files, “Greenwald—in my view—clearly has committed a felony.” His reporting “doesn’t border on criminality—it’s right in the heartland of criminality.” David Gregory, host of NBC’s Meet the Press, asked Greenwald, “To the extent that you have aided and abetted Snowden…why shouldn’t you, Mr. Greenwald, be charged with a crime?” A hostile story about Greenwald’s reporting by longtime Washington Post reporter Walter Pincus required a 200-word correction. New York Times financial columnist Andrew Ross Sorkin stated on his CNBC show: “I would arrest him [Snowden], and now I would almost arrest Glenn Greenwald.”

Major news organizations published baseless speculation about Snowden from nameless sources. The New York Times reported: “Two Western intelligence experts, who worked for major government spy agencies, said they believed that the Chinese government had managed to drain the contents of the four laptops that Mr. Snowden said he brought to Hong Kong.” Snowden was accused by officials and journalists of being a traitor who gave the NSA files to Russia in exchange for asylum there, and who gave files to China before he flew to Russia for a connecting flight to Latin America he was unable to make because the United States cancelled his passport while he was en route. Snowden has repeatedly stated that he took no files with him when he left Hong Kong and that he gave all of the files he had to journalists and not to any country.

The significance of Snowden’s revelations could not be denied. Nor could the high quality of the reporting by Greenwald and Poitras and also by Barton Gellman of The Washington Post and others with whom Greenwald and Poitras collaborated. Their stories prompted an international debate about the implications of massive surreptitious surveillance, about surveillance intended to humiliate targeted Muslims, about the right to privacy and about the far-reaching implications of a plan, being carried out with the NSA’s British counterpart GCHQ, to develop the capacity to tap into any phone, any time, anywhere in the world.

Nowhere was the anger about the surveillance of other countries’ citizens greater than in Germany, where brutal experiences with the Nazis’ Gestapo and the East German secret police, the dreaded Stasi, planted a deep and abiding understanding that creating the capacity to conduct mass surveillance portends using that capacity to engage in mass control of citizens.

In January, seven months after Greenwald’s first NSA reports, The New York Times called for Snowden, “in light of his role as a whistle-blower,” to be granted clemency: “Considering the enormous value of the information he has revealed, and the abuses he has exposed, Mr. Snowden deserves better than a life of permanent exile, fear and flight. He may have committed a crime to do so, but he has done his country a great service. It is time for the United States to offer Mr. Snowden a plea bargain or some form of clemency that would allow him to return home.”

In April, Greenwald, Poitras and Barton Gellman and their publications, The Guardian and The Washington Post, were awarded the top prize in American journalism, the Pulitzer Prize for public service reporting, and also the prestigious George Polk award, for their reports on the NSA files.

Despite intense global response to the the Snowden files, discussions in government chambers in many countries about the need for new intelligence policies and Greenwald’s major role in bringing the files to light, the publication of Greenwald’s book has prompted perhaps the harshest criticism of him. As more Americans moved toward seeing Snowden as a whistleblower rather than as a traitor, and Greenwald’s peers muted their criticism and honored him, Michael Kinsley declared in The New York Times Book Review that neither Greenwald nor other journalists should be able to decide to publish government secrets.

“The Snowden leaks were important,” wrote Kinsley, “and we might never have known about the N.S.A.’s lawbreaking if it hadn’t been for them.” Nevertheless, he continued, “In a democracy…that decision must ultimately be made by the government. … Someone gets to decide, and that someone can’t be Glenn Greenwald.”

His assertion that journalists should not decide to publish government secrets stands in opposition to some of the most important journalism. The Constitution provides for the press to be an important check on the power of government. History is replete with examples that show the necessity of that check. Intelligence agencies and other high-level government agencies seldom voluntarily reveal their excessive or illegal practices. Reporting by journalists—usually made possible by whistleblowers willing to risk their freedom to provide documentary evidence of official wrongdoing—is the usual path to exposure of government wrongdoing. For example, the public learned about the lies that were the basis of much of the rationale for the Vietnam War because The New York Times and The Washington Post in 1971 published the Pentagon Papers, the secret official history of the war given to newspapers by former Defense Department official Daniel Ellsberg, who was prosecuted. Similarly, the wall of secrecy that shielded a half-century of illegal cruel operations by the FBI under Director J. Edgar Hoover was cracked by a group of citizens determined to find evidence of whether the FBI was systematically suppressing dissent. They stole files from the FBI office in Media, Pennsylvania, in 1971 and gave them to journalists, including this writer, then a reporter at The Washington Post.

Snowden, the 30-year-old whistleblower at the heart of Greenwald’s important book, has been criminally charged under the 1917 Espionage Act for making public the evidence that the NSA conducts countless operations that are the antithesis of what most Americans would be willing to have done in their name. In doing so, he challenged journalists, the government, the American people and the international community to assume responsibility for what the future of this vast international electronic spying machine will be.

Betty MedsgerAs a Washington Post reporter in 1971, Betty Medsger wrote the first stories about the revelations in the stolen Media, Pennsylvania FBI files. In January 2014, Alfred A. Knopf published her book The Burglary: The Discovery of J. Edgar Hoover's Secret FBI, in which the burglars are revealed and the impact of their actions is told.