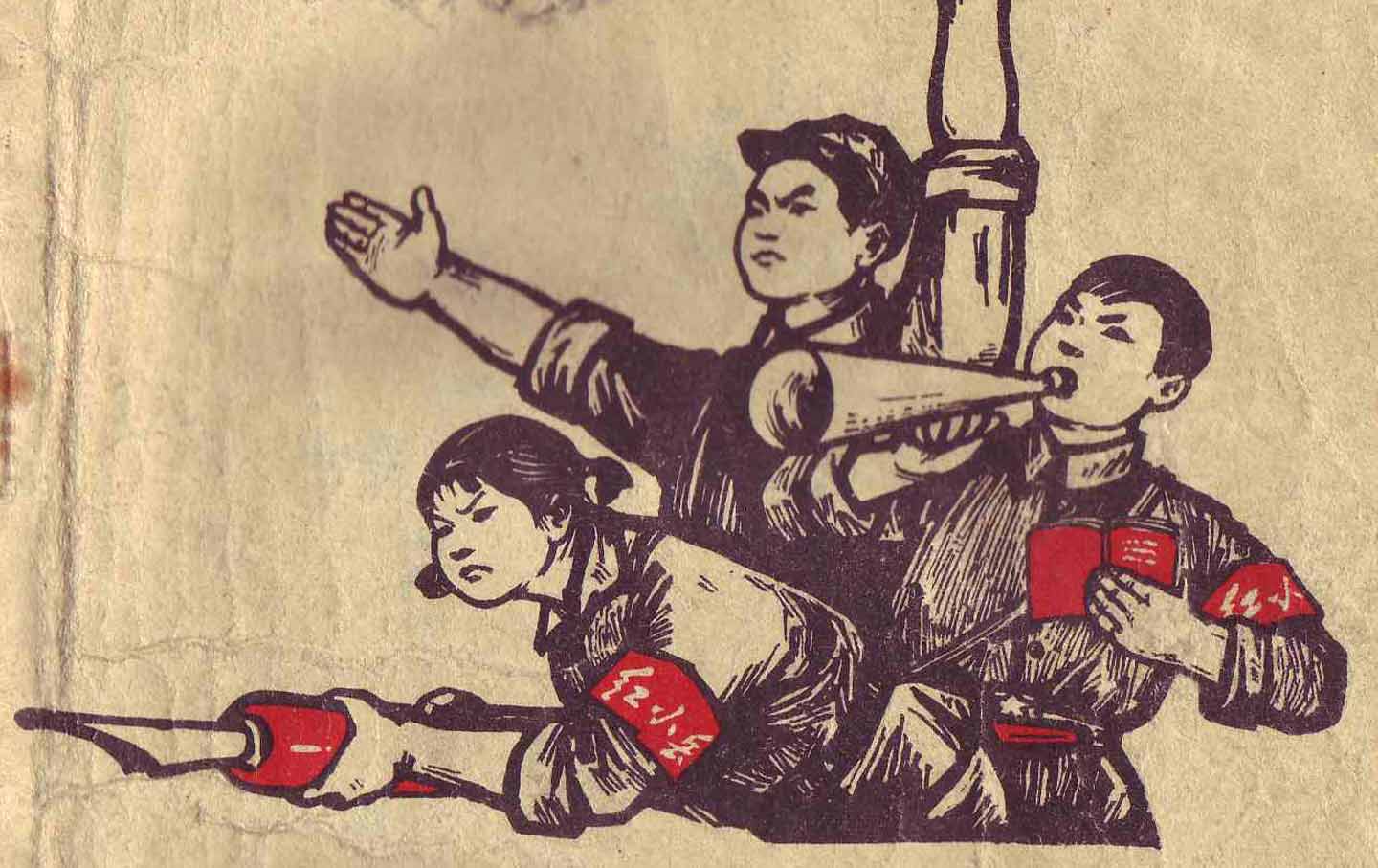

Red Guards on the cover of an elementary school textbook from Guangxi, 1971.

This month marks the anniversary of two surges of youth activism in China. One, the May 4 Movement, began with student protests 97 years ago. The other is the 50th anniversary of the Cultural Revolution, which is sometimes said to have begun with the first Red Guards putting up wall posters in late May of 1966. May 4 and Red Guard activists were once seen as part of related movements, but now they tend to be regarded as radically dissimilar.

The former event began with a rowdy May 4, 1919, demonstration in Beijing, during which, among other things, students trashed the houses of officials they despised and one student was injured in a scuffle with police, later dying from his wounds and becoming the struggle’s main martyr. The students who took to the streets were part of a generation fascinated with new ideas and ideologies coming into the country from other parts of the world, from Bolshevism to the democratic liberalism of John Dewey, who happened to arrive in Shanghai to give lectures a few days before the first protests broke out in Beijing. Dewey was brought to Shanghai by progressive intellectuals who had studied with him at Columbia. The May 4 students were also iconoclastic; like the progressive professors and literary figures they admired, they viewed Confucian beliefs and traditions as things that were holding their country and its people back. A third important thing about them was their fierce patriotism.

The May 4 demonstrators took to the streets to denounce warlord rulers whom they viewed as dictatorial, out of step with modern intellectual currents, and far too ready to accede to a plan that the World War I victors were hatching in Paris. This plan, enshrined in the Treaty of Versailles, ceded former German possessions in Shandong Province to Japan rather than returning them to China. Among the student participants in this protest, the professors who encouraged them, and the educated youths who joined follow-up demonstrations in other cities—which drew many workers and members of other groups into the streets as well—were several people who would go on to help found the Chinese Communist Party two years later.

This fact—as well as the success the movement had in achieving some of its goals, such as forcing the ouster of several officials they despised and getting Chinese diplomats to refuse to sign the Treaty of Versailles—helps explain why the CCP would decide in 1939 that the perfect date on which to celebrate “Youth Day” was May 4. It also explains why one of the friezes on a monument in the center of Tiananmen Square devoted to heroes of the Revolution shows a young participant in the May 4 Movement giving a speech, while his male and female classmates distribute pamphlets to a crowd made up of people from different walks of life. And it explains why Communist Party leaders, from Mao Zedong to Xi Jinping, have all periodically praised the May 4 activists.

The Cultural Revolution is much harder to sum up, so it will be enough here to say a bit about the Red Guards, the most famous—and infamous—group involved in it. These youths were intensely devoted to Mao, who was claiming by 1966 that the sacred revolution he had led was being endangered by the secret machinations of nefarious figures in positions of authority. He accused these people of only pretending to be “red” and patriotic, while really being “capitalist roaders” with bourgeois leanings, “traitors” in league with foreign powers, and “counter-revolutionaries” who had never shaken the hold of “feudal” Confucian ideas. The Red Guards accused administrators at their schools of being “counter-revolutionary” and lashed out at all sorts of real and imagined enemies of the “Great Helmsman” they worshiped, including his onetime heir apparent, Liu Shaoqi, whom Mao claimed was working to undermine his authority and reduce him to a figurehead.

Debates have long raged over how the Cultural Revolution spiraled into violence, involving everything from deadly beatings on campuses to pitched battles between rival groups on the streets of the capital and other cities. There are also conflicting views regarding the motivations, beliefs, activities, and legacies of the youths who got things started, who are the subject of a major new study by sociologist Guobin Yang that Columbia University Press will publish this month: The Red Guard Generation and Political Activism in China. Among the few things that no one questions about the Red Guards is their devotion to Mao (which made them unlike the May 4 activists, who did not look up to any powerful political figure of their day) and their iconoclastic tendencies and antagonism toward Confucian tradition, which was something that linked them to the young activists of 1919.

The best way to give a sense of how, at one point, the May 4 protesters and Red Guards were seen as cut from the same cloth is to look back to spring 1969, when the People’s Republic of China marked the 50th anniversary of the former movement. The May 5, 1969, issue of Peking Review, the most important Chinese Communist Party English-language magazine of the time, devoted two articles to the events of 1919. The first was a re-publication of “The Orientation of the Youth Movement,” a speech Mao gave in 1939, to mark the twentieth anniversary of the May 4 Movement and the proclamation of the date as Youth Day. The second was “The Jubilee of the May 4 Movement,” which was described as the joint creation of the editorial boards of Renmin ribao (People’s Daily) and two other leading Chinese-language official periodicals. That second article linked the events of 1919 to the accomplishments of the Cultural Revolution, which Mao had recently pronounced a success and declared over (though many now see the chaotic era that began in 1966 as lasting until the Chairman’s death, in 1976).

The central theme of this latter essay was that the “revolutionary youth movement” had achieved great things over the course of half a century. It had done so by moving from strength to strength and being able, in recent decades, to take its cues from Mao’s “brilliant writings” and speeches. The “revolutionary youth movement in China has developed over the last 50 years, from the stage of the new-democratic revolution to the stage of the socialist revolution, and on to the Red Guard Movement during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution,” the article asserts. “It has played a tremendous role in the history of the Chinese revolution.”

* * *

When did the notion take hold that the May 4 and Red Guard traditions should be seen as radically different, rather than part of the same lineage? It’s hard to say exactly, but by the time I made my first trip to China in 1986, twenty years after the first Red Guard troupes were formed, the ground had shifted dramatically. I arrived in Shanghai that August, to begin research on a dissertation dealing with pre-1949 episodes of youth activism, including both the 1919 protests themselves and later struggles, such as the December 9 Movement of 1935, which were seen at the time and have often been viewed since as part of a continuous and evolving “May 4” tradition.

By December of 1986, Chinese students had once again taken to the streets, calling on the government to move more quickly in the liberalizing direction of “reform and opening up” that Deng Xiaoping had made his watchwords. The youth were influenced by new ideas in the air, such as speeches calling for democracy that the astrophysicist Fang Lizhi had been giving, but they also explicitly rooted their struggle in history. The wall posters I read on campuses that year included calls for the current generation of students to align themselves with the patriotic and anti-autocratic actions of their predecessors in the May 4 and December 9 Movements—the second a particularly resonant event at the time, as official proclamations extolling its virtues and accomplishments had gone up just before the protest surge began.

As 1986 ended and 1987 began, however, and the authorities moved to get the struggle to wind down, a different sort of historical allusion began to appear on the walls of Shanghai campuses: calls for students to take care not to act like the Red Guards of the Cultural Revolution. The work of administrators and sometimes of conservative members of official student organizations, these notices that referred to protesters as resembling “New Red Guards” had a chilling effect. In this post-Mao period, the Cultural Revolution had come to be seen as a dangerously chaotic period, when youths were misled by their adoration for an aged leader, so to be like Red Guards was to be pulling China backward, not moving it forward, and to be allowing oneself to be hoodwinked as opposed to being independent. This was not how 1986’s protesters wanted to be seen.

This established a pattern that would be repeated during the much larger protest wave of 1989. The students issued one of their most stirring proclamations on the date of the seventieth anniversary of 1919’s first protests. Standing in front of the frieze devoted to the struggle in the heart of Tiananmen Square, they said that a “new May 4 Movement” was needed to get the revolution back on track. Once again, they insisted, China needed to be saved from misgovernment by leaders who were out of touch and autocratic. The government brought up the specter of the Red Guards to counter this, and frequently derided the students for fomenting “chaos,” a term that immediately brings the Cultural Revolution to many minds.

Something similar happened during Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement in 2014. The mainland media made much of the fact that one of the few times the city had been hit by protests like these, which were fueled largely by youthful enthusiasm, had been during the Cultural Revolution. Hong Kong had still been a British Crown Colony then, but it had not been immune to protests by local youths loyal to Mao. The Umbrella Movement was as basically peaceful as the 1989 protests on the mainland had been, but this did not stop official media from insisting, as CCP leaders had twenty-five years earlier, that there were youths on the streets acting like Red Guards and causing Cultural Revolution–style turmoil.

Hong Kong protesters did not make as much direct use of May 4 symbolism as the 1989 demonstrators in Beijing and other mainland cities did, in part because they framed their efforts in local terms. They did, however, scoff at the idea that they were reviving Cultural Revolution patterns in much the same way that their Tiananmen predecessors had done a quarter century before. Like mainland students in 1989, the Hong Kong ones of 2014 insisted that they were working to move a place they loved forward, not send it cycling back into the past, so it was completely misguided to tar them with the Red Guard brush.

Ironically, though the Umbrella protesters made fewer allusions to 1919 than the Tiananmen demonstrators did, one key aspect of their struggle made them more like May 4 activists than the 1989 students had been. The Tiananmen protests were about many things, but not about opposition to officials at home who were giving in too easily to demands coming from afar. In 2014, by contrast, when demonstrators derided Hong Kong Chief Executive C.Y. Leung and his allies, they claimed, as May 4 activists had said of the warlords and Chinese representatives at Versailles, that they were not just autocrats but ones too willing to do the bidding of people in a distant capital—this time in Beijing, rather than Europe.

In the era of Xi Jinping, with his fondness for quoting Confucius and warning of the danger of Western ideas, there is no room for commemorating key aspects of the May 4 tradition. It is no surprise, then, that when Youth Day arrived this year, Beijing’s official news agency, Xinhua, blandly described the 1919 protests as being worth remembering because they “inspired the Chinese people to be united and hard-working.” We should also expect to see little public discussion of the Red Guards later this month on the mainland. The Cultural Revolution, long a subject that Chinese leaders seek to handle with care, has become even more of a hot potato now that Xi’s image and writings are getting celebrated in a manner that seems uncomfortably similar at times to how Mao’s were in the 1960s.

We have grown used to Hong Kong being the one place in the People’s Republic of China where 1989’s Tiananmen protests can be publicly marked when the anniversary of the June 4 Massacre arrives each year. We can add to this that Hong Kong is also, despite disturbing recent efforts by Beijing to stifle its special public sphere, the one part of the PRC where frank public discussion of the Cultural Revolution’s legacy is possible on the fiftieth anniversary of the Red Guards’ first actions. It is also, importantly, the only place where the true spirit of May 4 is being kept alive by youths who combine openness to the best ideas coming from all corners of the globe with a determination to protect the political community they love.

Jeffrey WasserstromJeffrey Wasserstrom is Chancellor’s Professor of History at UC Irvine and the co-author of China in the 21st Century: What Everyone Needs to Know, the third edition of which was just published by Oxford University Press.