Few people in the Republican Party have done more to limit voting rights than Hans von Spakovsky. He’s been instrumental in spreading the myth of widespread voter fraud and backing new restrictions to make it harder to vote.

But it appears that von Spakovsky had an admirer in Neil Gorsuch, Donald Trump’s nominee for the Supreme Court, according to e-mails released to the Senate Judiciary Committee covering Gorsuch’s time working in the George W. Bush Administration.

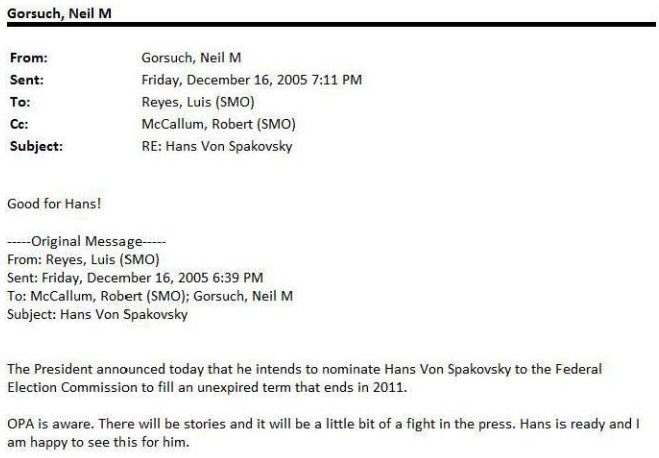

When President Bush nominated von Spakovksy to the Federal Election Commission in late 2005, Gorsuch wrote, “Good for Hans!”

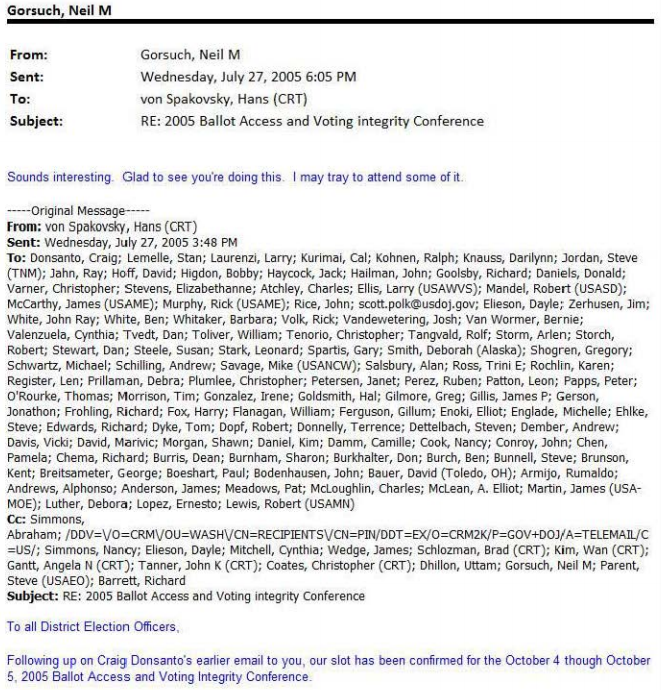

In another e-mail, when von Spakovksy said he was participating in a “Ballot Access and Voter Integrity Conference” at the Justice Department, Gorsuch wrote, “Sounds interesting. Glad to see you’re doing this. I may try to attend some of it.” Though the Justice Department was supposed to investigate both voting discrimination and voter fraud, the latter cause took priority and eventually led to Republican US Attorneys’ being wrongly fired from their jobs for refusing to prosecute fraud cases.

At very least, the e-mails suggest Gorsuch was friendly with von Spakovksy. But it’s far more disturbing if Gorsuch shares Von Spakovsky’s views on voting rights. Given that we know almost nothing about Gorsuch’s views on the subject, this is something the Senate needs to press him on during confirmation hearings next week.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Though the e-mails sound mundane, they’re much more important when you consider what was happening at the Justice Department during the time Gorsuch overlapped with von Spakovksy. In 2005–06 Gorsuch was principal deputy to the associate attorney general and von Spakosvky was special counsel to Brad Schlozman, the assistant attorney general for civil rights, who said he wanted to “gerrymander all of those crazy libs right out of the [voting] section.” It was a time when longtime civil-rights lawyers were pushed out of the Justice Department and the likes of Schlozman and von Spakovsky reversed the Civil Rights Division’s traditional role of safeguarding voting rights. When von Spakovsky was nominated to the FEC, six former lawyers in the voting section called him “the point person for undermining the Civil Rights Division’s mandate to protect voting rights.”

In particular, von Spakovsky manipulated the process to approve Georgia’s strict voter-ID law in 2005, which was among the first of its kind. (I tell this story in great detail in my book Give Us the Ballot.) Von Spakovsky had been an advocate of such laws nationally and in Georgia specifically, where he was from, since the 1990s. “Requiring official picture identification such as a driver’s license with a current address would immediately cut down on a large amount of fraud,” he wrote in The Wall Street Journal in 1995. Two years later, he recommended, “Georgia should require all potential voters to present reliable photo identifications at their polling locations to help prevent impostors from voting.”

Georgia’s voter-ID law was submitted to the Justice Department in 2005 under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, which required states like Georgia with a long history of voting discrimination to approve their voting changes with the federal government. The sponsor of the law, Republican Representative Sue Burmeister, told department lawyers, “If there are fewer black voters because of the bill, it will only be because there is less opportunity for fraud. She said when black voters in her precinct are not paid to vote, they do not go to the polls.”

Her racially inflammatory assertions set off alarm bells among the team reviewing the submission, indicating that the law may have been enacted with a discriminatory purpose. Department lawyers feared the bill would disenfranchise thousands of voters.

Atlanta’s Mayor, Shirley Franklin, told the story of her 84-year-old mother, who had recently moved from Philadelphia to Atlanta and could not obtain a new photo ID for voting. Her expired Pennsylvania driver’s license was rejected as sufficient documentation to obtain a Georgia ID card, and she was told to produce a copy of her birth certificate. But Franklin’s mother had been born at home in North Carolina and, like many elderly African Americans who grew up during Jim Crow, never had a birth certificate. After voting for 40 years, she would be disenfranchised by the new law.

Citing the high number of voters without ID, the disparate rates of ID possession among blacks and whites, the number of DMV offices that did not issue IDs, the cost of the ID and the underlying documents needed to obtain an ID (ranging from $20 for an ID card to $210 for naturalization papers), four of five members of the Georgia review team urged that the law be rejected under Section 5. “While no single piece of data confirms that blacks will [be] disparately impacted compared to whites, the totality of evidence points to that conclusion,” they wrote in a 51-page analysis.

Yet von Spakovsky placed a conservative lawyer on the review team, Joshua Rogers, who argued that the law should be approved. Von Spakovsky began secretly e-mailing Rogers copies of his articles, and arguments and analysis in favor of the Georgia ID law. He told him to password protect his computer so that no other attorneys on the team could see their correspondence. Rogers’s dissenting memo, which was drafted with von Spakovsky’s input, became the basis for the Justice Department’s preclearance of the law.

A year later, when von Spakovsky was nominated to the FEC, it was revealed that he published a law article praising voter-ID laws under the pseudonym “Publius” just a week after Georgia submitted its law for review. The article in the Texas Review of Law & Politics, a conservative legal journal, was titled “Securing the Integrity of American Elections: The Need for Change” and its author was identified as “an attorney who specializes in election issues.” Publius, aka von Spakovsky, wrote: “It is unfortunately true that in the great democracy in which we live, voter fraud has had a long and studied role in our elections,” the article began. It continued: “putting security measures in place— such as requiring identification when voting— does not disenfranchise voters and there is no evidence to suggest otherwise.”

DOJ ethics guidelines clearly stated that von Spakovsky, given his longstanding advocacy for voter-ID laws and the strong viewpoints in his then-anonymous article, should have recused himself from consideration of Georgia’s law. Indeed, his ethical lapses and deceptive support for new voting restrictions were a major reason Senate Democrats blocked his nomination to the FEC and President Bush was forced to give him a recess appointment. (Then-Senator Barack Obama put a hold on von Spakovsky’s nomination and he withdrew in 2008, joining the Heritage Foundation, which has championed Gorsuch’s nomination.)

But that’s not all. In addition to the FEC, Von Spakovsky was also appointed to the advisory board of the Election Assistance Commission, created by the Help America Vote Act to analyze the country’s election problems. The commission hired two well- respected experts, Republican Job Serebrov and Democrat Tova Wang, to produce a comprehensive study on voter fraud. “There is widespread but not unanimous agreement that there is little polling place fraud, or at least much less than is claimed, including voter impersonation, ‘dead’ voters, non-citizen voting and felon voters,” a draft of the report stated. After von Spakovsky complained to the commission’s GOP leadership, the wording in the final report was changed to, “There is a great deal of debate on the pervasiveness of fraud.”

More recently, von Spakovsky has argued against that the Voting Rights Act was “constitutionally dubious at the time of its enactment” and praised Trump’s promised investigation into voter fraud, which has been widely panned by Democrats and Republicans. “The real problem in our election system is that we don’t really know to what extent President Trump’s claim is true because we have an election system that is based on the honor system,” he wrote with John Fund after Trump said with no evidence that 3 million to 5 million people voted illegally.

Given that von Spakovsky hailed Gorsuch as “the perfect pick for Trump,” it’s safe to assume he believes that the Supreme Court nominee shares his views. The Senate needs to aggressively question Gorsuch to see if that’s the case.

Gorsuch has already cited Justice Antonin Scalia as a role model, who said the Voting Rights Act had led to a “perpetuation of racial entitlement.” Gorsuch, if confirmed, could be the deciding vote on whether to weaken the remaining sections of the VRA and whether to uphold discriminatory voter-ID laws and redistricting plans from states like North Carolina and Texas. In many ways, the fate of voting rights in the United States hangs on this nomination.