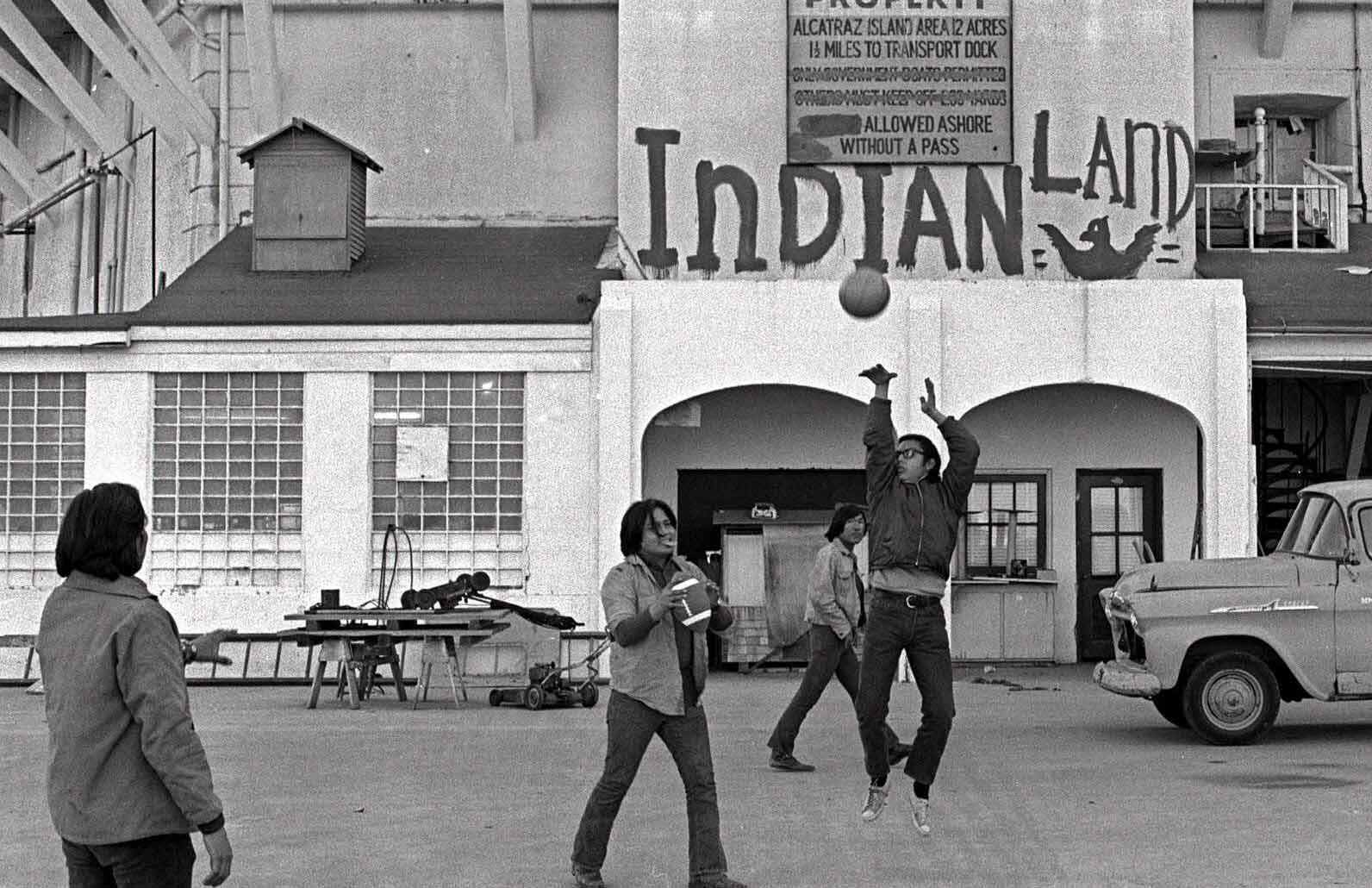

American Indians play ball games outside the prison wall on Alcatraz Island in San Francisco during their occupation of the island in November 1969.(AP)

“Go back to where you came from!” a white woman screamed at us at the Los Angeles International Airport. We laughed at the absurdity of the notion. The biting humor of the late Haudenosaunee and Cree comedian Charlie Hill quickly came to mind: “A redneck told me to go back to where I came from, so I put up a tipi in his backyard!”

“Go Back to Where You Came From,” by Nick Estes, was originally commissioned by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s Open Space platform and published on November 4, 2019 as part of the magazine Alcatraz Is Not an Island, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Indigenous Occupation of Alcatraz. Guest edited by Dr. LaNada War Jack, a Shoshone-Bannock tribal member and co-leader of the Occupation, and Julian Brave NoiseCat of Oakland and the Canin Lake Band Tsq’escen, who is a co-founder of the Alcatraz Canoe Journey.

That sunny day in early 2017, we marched behind Tongva drummers, the original people of what is currently Los Angeles. We held placards that read “No Ban On Stolen Land!” protesting Donald Trump’s executive order barring travel to the United States from seven Muslim-majority countries in Africa and the Middle East. This defiance is the living legacy of centuries of indigenous resistance: the active refusal to cede moral authority over who belongs and who doesn’t to a settler nation.

But America has only room for winners and losers, we’re told. By that standard, Indians are the constant losers of history. And, for that matter, so too is anyone who doesn’t immediately buy what America is selling. The narrative we’re sold is that indigenous resistance is a string of failures. That same year, Water Protectors “lost” at Standing Rock because the Dakota Access Pipeline was built. Later, the Wetʼsuwetʼen “lost” because Unist’ot’en Camp had been raided by police and the land occupied by Coastal Gas Link pipeline workers. More recently, the kia’i “lost” at Mauna Kea because the mainstream media was obsessed with “science versus culture”—not indigenous land rights—and the Kanaka Maoli needed to relinquish “superstition” and accept “progress” as “inevitable” by having a $3.4 billion telescope built next to 22 other telescopes on their sacred mountain.

While indigenous people are told to “quit living in the past,” settlers are urged to “Make America Great Again” by invoking the country’s mythic halcyon days. That’s the story America likes to tell itself: the story of winning the future of this land by winning its past. The truth is quite the opposite: America fears the past.

Reduced to its basic components, the history of colonization boils down to three things: gold, God, and glory. Natives had all the gold. Settlers brought God. Now the Natives have God and the settlers have all the gold, the story goes. But glory is the most precarious elements of this formula. Is there honor in invasion, slavery, genocide, and theft? The answer to that question changes throughout time. But we don’t have to journey too far into history to see that the response, by Indigenous standards, is clearly no. If anything, paradoxically, glory belongs to history’s losers.

In 1971, Richard Nixon ordered the police to evict Indians of All Tribes from Alcatraz Island, after 19 months of steady encampment by the indigenous group in the former federal prison. The protest, however, is not remembered for its failure to achieve its stated goals of reclaiming the Ohlone land for all indigenous peoples and creating an “all-Indian university.” Instead, it is remembered for the movement that sparked an era of Red Power militancy. And Alcatraz resonated beyond the confines of just the indigenous movement.

In 1969, a young black revolutionary who later took the name Assata Shakur visited the island, offering her services as a medic. She marveled at the “quiet confidence” of the Indigenous activists who had founded a new community, one based on their cultural and spiritual traditions, in and around what was once a notorious penitentiary. Shakur had discovered some of the current Native occupiers were once former Alcatraz prisoners.

The prison island was also the site where four Modoc were hanged, and where Pauite and Apache prisoners of war and other Western indigenous nations were imprisoned in the late 19th century for resisting invasion by the United States. In 1894, the military imprisoned 19 Hopi men at Alcatraz as punishment for refusing to send their children to government- and church-run boarding schools. The indigenous prisoners of Alcatraz had faced similar conditions that Red Power activists had faced: a harsh landscape purposefully isolated from the rest of the world, uninhabitable, abandoned, and in disrepair, much like the Indian reservations from which they had come.

“They [Indians] damn sure had the same enemy,” Shakur recalled, seeing similarities in black and indigenous experiences. She told her new comrades that if they ever visited New York to look her up in Harlem. “Sure. When are you going to liberate it?” they asked her.

Alcatraz catalyzed an indigenous movement that kicked off occupations of federal lands and buildings across the continent, the height of which occurred during the 71-day siege at Wounded Knee, where indigenous activists took over the small town in the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, demanded the ouster of a corrupt tribal administration, and declared independence from the United States. While a captivated public only saw the spectacle of militant Native men in braids and shades brandishing firearms, James Baldwin saw something else.

“What Americans mean by ‘history’ is something they can forget,” he said, reflecting on this period of indigenous uprisings. “They don’t know they have to pay for their history, because the Indians have paid for it every inch and every hour. That’s why they’re at Wounded Knee; that’s why they took Alcatraz.”

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation

Perhaps because they have paid such a heavy price for history, Natives have capacious notions of freedom and belonging. At Alcatraz and at Standing Rock, indigenous peoples turned those seen as different into familiars, into allies. They made relations. This is the quiet strength, the victory of indigenous movements over time, the power of love and humanity that doesn’t make headlines.

At the LAX airport protest in 2017, the Tongva drummers surrounded a Muslim family, singing to them a song of honor. The singers welcomed them to their homelands. Tears streamed down a young girl’s face. She wore a hijab. Moments earlier, she appeared frightened. Now at peace. This is what it means to go back to where you came from. Nothing about the complex human condition of shared grief, love, and solidarity is alien to that place of freedom. Call it home.

Nick EstesNick Estes is a citizen of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe and an assistant professor of American Studies at the University of New Mexico. In 2014, he co-founded the Red Nation. He is the author of Our History is the Future (Verso, 2019).