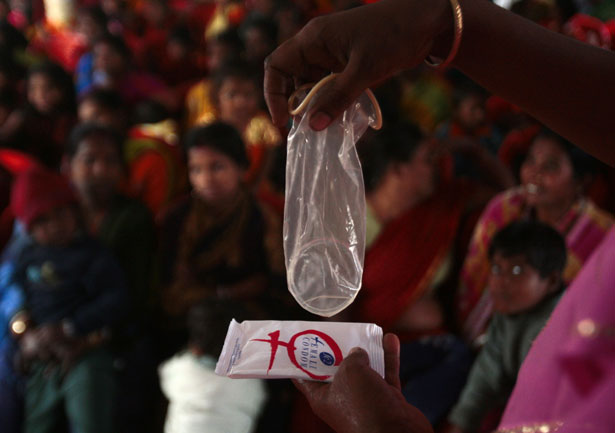

A sex worker demonstrates the use of a female condom during an HIV/AIDS awareness campaign organized by a NGO in Siliguri, India, on February 15, 2010. (Reuters/Rupak De Chowdhuri)

Ten years ago, the United States dramatically ramped up AIDS funding, but the funding came with this dangerous string attached: in order to qualify, non-governmental organizations must adopt an explicit policy opposing prostitution. Proposed by Republican Representative Chris Smith as an amendment to the landmark AIDS legislation the Global Leadership Against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria Act (or, PEPFAR, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief), this anti-prostitution pledge requirement was a conservative attempt to conflate offering HIV prevention and treatment to sex workers with promoting the actual practice of prostitution. Some feminist organizations—like the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women and Equality Now—who oppose prostitution and sex work have also supported the pledge requirement. This April, after several years of legal challenges in lower courts brought by health and rights advocates, the United States had to defend the anti-prostitution pledge in front of the Supreme Court. Its decision is expected this month.

In the decade that’s passed since the pledge was made a requirement of AIDS funding recipients, it’s become more difficult for some prevention projects to reach sex workers, and others have had to close completely. As reported in the Journal of the International AIDS Society, the vague language of the pledge—as well as its political roots in attempts to eradicate sex work—has meant that PEPFAR recipients are left to interpret the pledge broadly, which in some cases has led them to cease providing any services to sex workers, lest they lose all their funding.

Some projects have been targeted more than others, notes a brief from the Center for Health and Gender Equity. “Because drop-in-centers offer control, knowledge, and some degree of comfort to sex workers,” their researchers found, “they have been a particular target under U.S. policy.” Durjoy Nari Shangho’s drop-in center in Bangladesh lost their funding as a result of their NGO sponsor signing the pledge. As a result, the street-based sex workers they served, the majority of whom are homeless, were without a place to sleep, bathe or use a bathroom—or a safe space in which to educate one another about HIV and prevention. Representative Chris Smith attempted to explain the US denial of funds to these kinds of programs and their resultant service closures as necessary to prevent PEPFAR from becoming “potential funding for pimps and traffickers.”

One program was in Smith’s sights in particular: SANGRAM, based in India, recognized by both USAID and UNAIDS as a best-practice model. SANGRAM refused to sign the pledge, and notified USAID that it would be returning its funds—which was described by the media as a US decision to defund SANGRAM, claiming it was trafficking children. Why was a program lauded for being such a good partner now suddenly recast as the enemy? Smith used this “case” as justification to fight for the pledge, while Representative Mark Souder, then a Republican Congressman from Indiana, complained—and apparently lied—to USAID that “funding for SANGRAM was terminated only after a concentrated effort by the State Department’s Trafficking in Persons office.”

As some members of Congress use sex workers’ health in much the same way they use women’s health and abortion, targeted AIDS projects have seen their funding cut and services cease and sex workers have paid the price. Notably, the United States exempted some US-funding recipients recipients from the pledge—the Global Fund for AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the World Health Organization, the International AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition and all UN agencies. But as Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor told the US attorney Sri Srinivasan this April as he defended the pledge, “I would have less problem accepting your message if there weren’t four major organizations who were exempted from the policy requirement. There seems to be a bit of selection on the part of the government in terms of who it wants to work with.” Chris Smith, the pledge’s architect, has certainly shown this to be true—at the expense of not just sex workers’ health but the fight against AIDS.