In the midst of our deepening recession, the United States faces another economic crisis that is less visible but may be more important than house foreclosures, bank failures, plant closings or stock market avalanches: the systematic under-investment in technology and innovation. Our global economic leadership may be at stake because of it.

But with only a little bit of extra funding, foresight and determination, it may be possible to kick-start an innovation revival. Especially at the federal level, we see an opportunity for a modest investment to create a whole new generation of idea-growing, job-creating technology hubs all across the country–perhaps even an “automotive Silicon Valley” in otherwise moribund Detroit.

This revival would not just be about investing more heavily in research and development. In troubled times like these, we need to remind ourselves that innovation has always been a crucial part of the American patrimony. It is as much a byproduct of our political system and cultural norms as of our business and scientific practices.

This patrimony is now at risk, not only because of our failure to invest but also because of our failure to reward and honor scientists, technicians, engineers and inventors above lawyers, bankers and hedge fund managers. We need to recognize the central role that real innovation of all kinds has always played in the American story.

Leadership

For more than a century America has led the world in innovation. This has been true not only in science and technology but also in business management practices, the design of new approaches to service delivery, political institutions and civil rights. A consistent track record of ingenuity and invention, complemented by heavy investments in education and science, has contributed mightily to America’s leadership role in the world economy, to our democratic culture and the prosperity of our people.

Most students of economic growth now agree that technical innovation’s contribution to US national wealth has been at least as important as that of so-called “natural” resources like abundant farmland, labor, capital, and energy.

In the post-globalization economy, where access to such resources is being commoditized, innovation has become an even more important source of competitive advantage. In principle, this should be good news for the United States. Innovation-based competition is a “win-win” scenario: over time, every player in the competitive game stands to benefit from the discoveries made by others.

But if the United Stakes stakes its future on resource-based competition–the kind of low-innovation, “big houses/big debts/big cars” model favored by automakers, Wall Street and the oil industry–the competitive game becomes “win-lose.” Long-term competitive advantage shifts to countries with the largest supply of cheap resources, the lowest taxes and the cheapest, most oppressed workers–not a formula for vibrant democracies either at home or abroad.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

High Returns

Unfortunately, our global leadership in innovation has been placed at risk in the United States by years of failure to invest adequate resources in R&D.

Virtually every analysis of the “social returns” of R&D investments–private profits and social benefits, like job creation–finds these returns to be from 30 percent to 50 percent per year or more in real terms. This compares with the meager 5 percent to 7 percent returns typically generated by the US stock market, and the minus-46 percent returns earned by a US stock portfolio over the last year.

These high returns to R&D are explained by its peculiar nature. Once discovered, new ideas can be used over and over at low–or even zero–marginal cost. So R&D not only boosts productivity in the industries that do research; it also yields “spillover” benefits for other industries. And it speeds up future innovations. There is not a finite body of good ideas sitting out there waiting to be mined. Rather, from a knowledge standpoint, we live in an expanding universe, where each new discovery reveals whole new territories to be explored.

Consistent with this, those industries that are the most R&D-intensive have also consistently achieved the highest growth rates and profitability, and have also made the largest contributions to skilled employment, high incomes and trade. The notable exceptions–financial services, lawyering, real estate development, accounting, as well as cartelized industries like autos, cable television, and oil and gas–are ones in which clever chicanery, market power and anti-competitive regulations have contrived to create vast fortunes without much fundamental innovation at all–until the recent collapse.

The Innovation Gap

These high rewards for investments in R&D also suggest the presence of a substantial innovation spending gap. This is the gap between the current level of R&D spending and the optimal level, from the standpoint of generating growth and employment, and the many other social benefits of new ideas. We appear to be so far from the competitive margin that the United States might be able to profitably invest several times the current $370 billion per year that industry and the federal government now spend on R&D without driving “social returns” below the federal government’s long-term cost of capital–just 1 percent these days, after inflation.

With such low real interest rates, and such high expected returns, it would cost the US government only about $400 million per year in interest to double its entire current budget for civilian R&D–which, in turn, might yield an incremental $12 billion in profits and other social benefits. It’s about time that we realized such high multiples for the country, not just Wall Street executives.

Yet the recent trend in US R&D investment has been in precisely the opposite direction. Historically, our R&D spending as a share of national income has been relatively high for decades, compared to other Western countries’, but since the mid-1980s it has stagnated. It now is well below the 1960s level, when the Kennedy/Johnson administrations’ visionary drive to reach the moon, combined with the arms race and the rise of mainframe computing, produced a sharp boost.

Federal funding is one key to closing this gap. While it still accounts for about 28 percent of all US R&D spending, it has been especially sluggish in recent years. In real terms, the federal budget for basic and applied R&D has fallen for five years in a row, and will continue to slide next year under the budget just approved by Congress.

This trend is even more disturbing once we take into account the fact that nearly 60 percent of the federal government’s current $100 billion of R&D funding is devoted to military and national security programs at the Pentagon, the Department of Energy and the Department of Homeland Security.

The modest $42.6 billion left over for all federal non-military research in FY 2009 has to fund everything from DOE’s basic research on alternative energy to the National Institute of Health’s vital medical research program for peer-reviewed science, to NASA’s entire space budget. As a share of national income, non-military budget for R&D now amounts to a paltry .3 per cent–the lowest share since the early 1950s, and just half the average in the late 1970s.

The $43 billion for civilian R&D pales in comparison to the $700 billion that the US Treasury is injecting into US banks, in return for some combination of non-voting stock, very low dividends and toxic assets. It also pales by comparison with the $29 billion bailout of Bear Stearns, the $135 billion bailout of AIG, the $200 billion bailout of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, let alone the $800 billion cost (to date) of the Iraq War.

Don’t Look Back

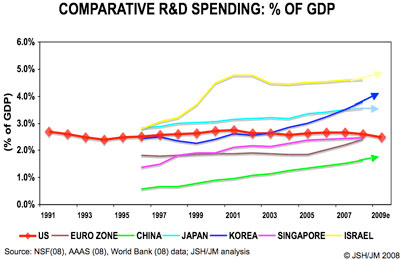

The other disturbing point about R&D spending is that American leadership has been slipping. Relative to other countries, the United States has long devoted a relatively high share of national income to R&D investment. Even now, it still accounts for a disproportionate share of all global R&D–at least 25 to 34 percent.

But while US R&D spending stagnates, key new competitors like China and Malaysia–and more mature ones like Korea, Singapore and the Nordic block–have been sharply increasing their innovation investment. And since innovation is by definition a matter of human skill and creativity, not just finance, it also matters that these new competitors have also sharply increased the share of skilled researchers and technicians in their labor forces. Our slippage has also been aided by our invisible “hegemon tax”– the 50 to 60 percent share of R&D the US spends on warfare innovations.

Overall, many high-growth developing countries have already grasped a key point about economic national security that the United States is still struggling with: the global competitive marathon increasingly depends on productivity, innovation and scientific skill, not just command over natural resources or vast pools of untutored laborers.

US companies that once moved offshore simply because of cheaper inputs, lower taxes and weaker regulation are now finding that it pays to move their R&D centers offshore as well. This is partly because of the growing availability of engineering skills in places like India, China and Singapore, but it is also because of the higher barriers to immigration that foreign skilled workers have faced in the wake of 9/11. This policy may or may not have had much impact on terrorism, but by forcing these workers to remain at home, it has certainly had a negative impact on our economic security.

Troubled Waters: Private R&D

These disturbing trends in federal innovation spending have also been reinforced by recent trends in the private sector. As we saw earlier, private investment now accounts for more than 70 percent of all US R&D. Unfortunately, because of the current financial crisis and the emerging recession, this funding is drying up even as we speak.

This is especially true for venture capital funds that have relied heavily on so-called “limited partners” like pension funds and university endowments. Such investors often manage their portfolios with fixed allocations–reserving, say, 10 to 20 percent of investments to “alternative investments,” especially the development side of R&D-intensive ventures. Given the stock market’s steep decline, this approach to portfolio management and the need to rebalance asset allocations have virtually dictated a steep decline in private R&D funding.

Depending on how deep this recession is, and how much farther stock markets fall, this portfolio allocation effect will easily trim private R&D spending by 10-20 percent or more–in a budget that is already under-funded.

In uncertain times like these, when capitalism is most in need of real breakthroughs, many private corporations and investors become less patient and much less willing to invest in the kind of low-probability, long-lead-time projects that are the essence of basic research.

Solutions

So what should we do about the innovation gap?

•

Stop eating the seed corn.

We must make investing in innovation the national priority that it deserves to be.

We need a significant boost in the current level of civilian R&D funding, along with increased tax credits and other incentives for basic research. Of course, this would require some increased federal spending, precisely at a time when the federal budget is likely to be strained. But as we’ve argued, the incremental amounts required are modest, while the paybacks are huge–the United States is just “one-half bank bailout” away from the kind of R&D funding that is needed.

We have to make this investment. As new competitors like China and India devote larger and larger shares of national wealth to technology, and keep more and more of their national savings at home, the days when we could simply borrow, cost-cut or “Wal-Mart” our way to prosperity are over.

•

Develop a solid technology strategy.

This is not a matter of industrial policy, picking winners or displacing private funding with government venture capital. We need to develop creative new ways to partner with private capital–including philanthropic donors and university endowments. The aim is to multiply the benefits, by focusing on what the government has always done best–replenishing the “seed-corn” with fundamental longer-term research.

This requires a fresh look at the appropriate role of government in innovation. From this angle, the current financial crisis may not be all bad. Given the disastrous example of excessive reliance on under-regulated markets and the proven track record of government R&D, this is an historic opportunity to design new ways for government and markets to collaborate .

•

Learn from our own innovation history.

Take a lesson from successful public-private collaborations in technology hubs like Silicon Valley, Boston and Austin. In all these cases, private venture capital and entrepreneurs played crucial roles–and so did federal dollars. For decades the federal government generously subsidized basic research in fields like engineering, biology, physics, chemistry and computer science at premier universities like MIT, Harvard, Stanford, Carnegie Mellon and the University of Texas.

Stanford University, for example, has received enormous federal research subsidies since the 1940s, and has become one of Silicon Valley’s mainstays. Combined with the valley’s highly competitive venture community, this provided the foundation for a technology hub that has transformed the world, with innovations like semiconductors, computer graphics and wireless communications, and companies like Intel, Apple and Google.

In Boston, the National Institutes of Health has played a key role in helping the community become a technology hub for biotech and pharma research. Boston’s leadership in this arena is based on significant NIH funding, channeled to peer-reviewed researchers at regional teaching hospitals. Over time, the steady provision of federal tax dollars has supplied the grist for what has since become a self-sustaining innovation mill.

The questino is whether we can replicate innovative new Bostons and Silicon Valleys in other geographies, focused on energy, healthcare, the environment, education and transportation.

The point is not to dictate precisely what gets worked on but to marshal the human resources and infrastructure needed for innovation, build the partnerships with private institutions and insist on excellence.

What conditions would be needed to yield a period of sustained innovation in the automobile sector? Why not reserve, say, just a few percent of the $25 billion that the federal government is committing to the bailout of that industry’s aging giants for the creation of an “automotive Silicon Valley”?

In such a hub, just as in Boston and Austin, a virtuous cycle of innovation and product development might be generated. Pockets of entrepreneurial companies would spawn others, competing aggressively and helping to free people and capital from big, slow-moving companies. Universities, communities and corporations would complement each other’s very different styles and skills.

Longer term, a renewed focus on innovation as a source of national competitive advantage will also require us to reform and fundamentally redirect our education system, in order to deliver tens of thousands of highly skilled scientists and engineers. There’s also a need for immigration reform to permit greater access to foreign-trained skills as an an alternative to the current scarce-visa system, which basically encourages potential skilled immigrants to stay at home, and our strongest competitor-countries to staff up their own technology-based industries. In this case, we’re not just eating the seed corn; we’re giving it away.

Finally, we need to nurture a national culture that reminds young people of their country’s innovation heritage and encourages them to become engineers, designers and scientists, rather than just lawyers, accountants and bankers–whose preferred form of ingenuity, in Thornstein Veblen’s words, has always been “clever chicanery, or the thwarting thereof.” Now more than ever, in the interests of the planet as well as the nation, we need to curtail all this chicanery once and for all, and return to that stronger, prouder American business tradition, innovation on the real side of the economy.