It has ignored repression by regimes close to Washington and dismissed criticism—by Nobel laureates—of its conflicts of interest.

Mark Weisbrot

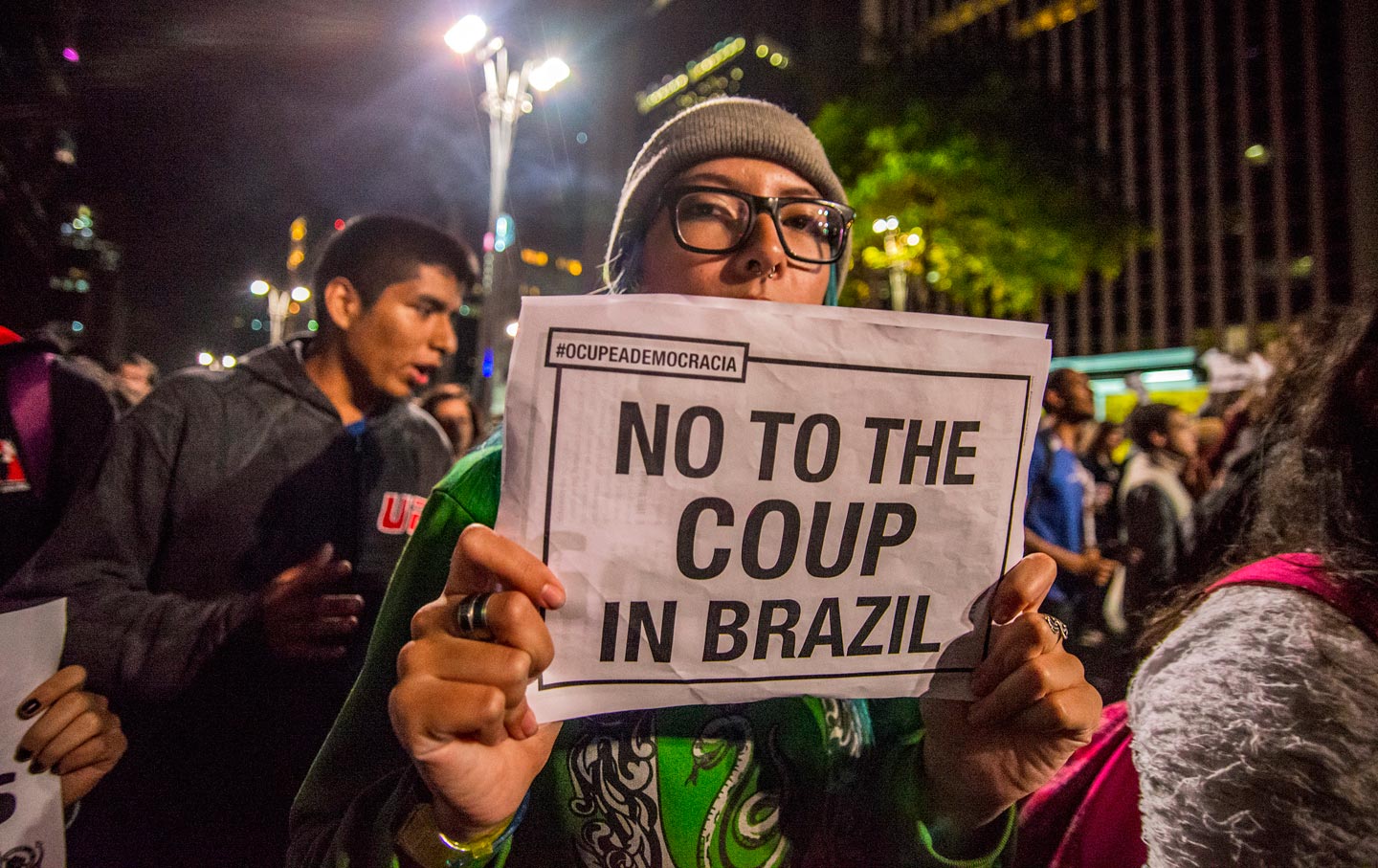

Supporters of Dilma Rousseff demonstrate after she was stripped of the country’s presidency by a Senate impeachment vote in São Paulo, Brazil.(Cris Faga / NurPhoto via AP Images)

Human-rights organizations are supposed to defend universal principles such as the rule of law and freedom from state repression. But when they are based in the United States and become close to the US government, they often find themselves aligned with US foreign policy. This damages their credibility and can hurt the cause of human rights.

Recent events in Latin America have highlighted this problem. On August 29, the Brazilian Senate removed the elected president, Dilma Rousseff, from office, even though the federal prosecutor assigned to her case had determined that the accounting procedures for which she was being impeached did not constitute a crime. Moreover, leaked transcripts of phone calls between political leaders of the impeachment showed that they were trying to get rid of Dilma in order to protect themselves from investigations into their own corruption.

Michel Temer, who has already been banned from running for office because of campaign finance violations, replaced an elected president who had committed no crime. Everything about the process was political—and now the new government is trying to implement a right-wing agenda that was defeated in the last three presidential elections.

Part of that right-wing agenda is a close alliance with the United States and its Cold War strategy of “containment” and “rollback” with respect to the left governments in Latin America. And that is where Human Rights Watch, the most prominent US-based human-rights organization—its Americas Division in particular—comes in. HRW abstained from offering the slightest criticism of the impeachment process; even worse, the executive director of its Americas Division, José Miguel Vivanco, was quoted in the Brazilian media—on the day that the Brazilian Senate voted to permanently oust the president—saying Brazilians “should be proud of the example they are giving the world.” He also praised the “independence of the judiciary” in Brazil. Sérgio Moro, the judge investigating the political corruption cases, has been far from independent. He had to apologize in March for leaking wiretapped conversations to the press between former president Lula da Silva and Dilma; Lula and his attorney; and between Lula’s wife and their children.

Vivanco also appeared to endorse the political persecution of Argentina’s former president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, while praising her replacement, the right-wing, US-backed Mauricio Macri. “An institution gains credibility when it is able to confront whoever it may be,” he said, referring to the current prosecution of Fernández. Of course, investigations into corruption of any government official, including a former president, can be perfectly legitimate. But Fernández, her former finance minister, and the former head of the central bank have been indicted for conducting what any economist knows is nothing more than a normal central-bank operation. This is clearly a case of trying to remove from politics a leftist former president who, together with her predecessor and late husband, Néstor Kirchner, presided over an enormous increase in living standards over a period of 12 years. This kind of political repression should be a serious concern for human-rights organizations, but there has not been a word about it in Washington.

Of course, all of this behavior aligns closely with US foreign policy in the region; for example, the Obama administration has clearly demonstrated its support for the Brazilian coup. On August 5, Secretary of State John Kerry met with the acting foreign minister of Brazil and held a joint press conference with him about the positive future of US-Brazilian relations. By making these joint statements and acting as if this was already the actual government of Brazil, when the Brazilian Senate had not yet decided the fate of the elected president, Kerry made it clear where the US government stood. The State Department had already sent a similar signal in May, just three days after the Brazilian lower house voted to impeach Dilma.

And President Obama made very clear his preference for the new right-wing government of Argentina, with the Obama administration lifting its opposition to loans from multilateral organizations that it had imposed during the prior left government, which of course contributed to the country’s balance-of-payments problems.

When asked why HRW hadn’t issued any statement about the Brazilian impeachment, Vivanco responded:

We don’t get involved in critiquing impeachment proceedings and other local political developments, except when they pose a significant threat to human rights and the rule of law. So, for instance, we denounced the coup d’état that ousted Honduran President Manuel Zelaya in 2009, as well as the one that briefly ousted President Hugo Chavez in 2002. But the situation in Brazil is not like these. Whether one agrees with the outcome or not, this [is] a political process occurring in a country with an independent judiciary capable of determining whether the laws governing that process are being respected.

But the impeachment process raised very serious questions about the independence of Brazil’s judiciary, as well as the rule of law, as noted above and elsewhere. And when the Honduran military overthrew President Zelaya, HRW’s Americas Division did very little. It posted a few statements on its website in the months following the coup, but these were largely pro forma. HRW has access to the most important US media, in opinion and news, and can usually place effective, high-profile op-eds when it chooses to make the effort. Yet, in the months following the Honduran coup, there was nothing in the media from HRW. And HRW, unlike the OAS, the UN, and the rest of the world, never called for the restoration of the democratically elected president. During this time, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton worked successfully to prevent Zelaya from returning to office (which she admitted in her 2014 book).

Although it sometimes denounces human-rights violations by pro-US governments, the Americas Division of HRW has also at times ignored or paid little attention to terrible crimes that are committed in collaboration with the US government in this hemisphere. Some of the worst examples include the overthrow of the elected government of Haiti in 2004, after which thousands were killed and officials of the constitutional government were jailed.

The OAS also has a checkered history with regard to human rights—it even played a significant role in the ouster of Haiti’s elected president in 2004 and reversed Haiti’s 2010 election results at the behest of Washington. But the OAS’s Inter-American Commission on Human Rights issued a statement in September expressing its concern over Dilma’s impeachment, and the OAS secretary general—a staunch US ally—issued a detailed denunciation, in much stronger terms, when the impeachment process began. All this is in sharp contrast to Vivanco’s statements on behalf of HRW’s Americas Division.

HRW has repeatedly and summarily dismissed or ignored sincere and thoroughly documented criticisms of its conflicts of interest. These include letters from Nobel laureates, former high-ranking UN officials, and scholars asking HRW to “bar those who have crafted or executed U.S. foreign policy from serving as HRW staff, advisors or board members,” or even to bar “those who bear direct responsibility for human rights violations” from participating on the boards of directors of independent human rights organizations like HRW.

Governments that commit human-rights abuses—and this includes just about every government in the world—often attack Western human-rights organizations or their (sometimes US-funded) domestic allies as tools of Western governments. This helps them degrade the legitimate struggle for human rights and even rally nationalist support for authoritarian governments, or for abuses committed by democratic governments. It is therefore vitally important that human-rights organizations stick to their avowed principles and defend human rights without regard to the objectives of US foreign policy.

Mark WeisbrotMark Weisbrot is codirector of the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington, D.C., and president of Just Foreign Policy. His latest book is Failed: What the "Experts" Got Wrong About the Global Economy (2015, Oxford University Press).