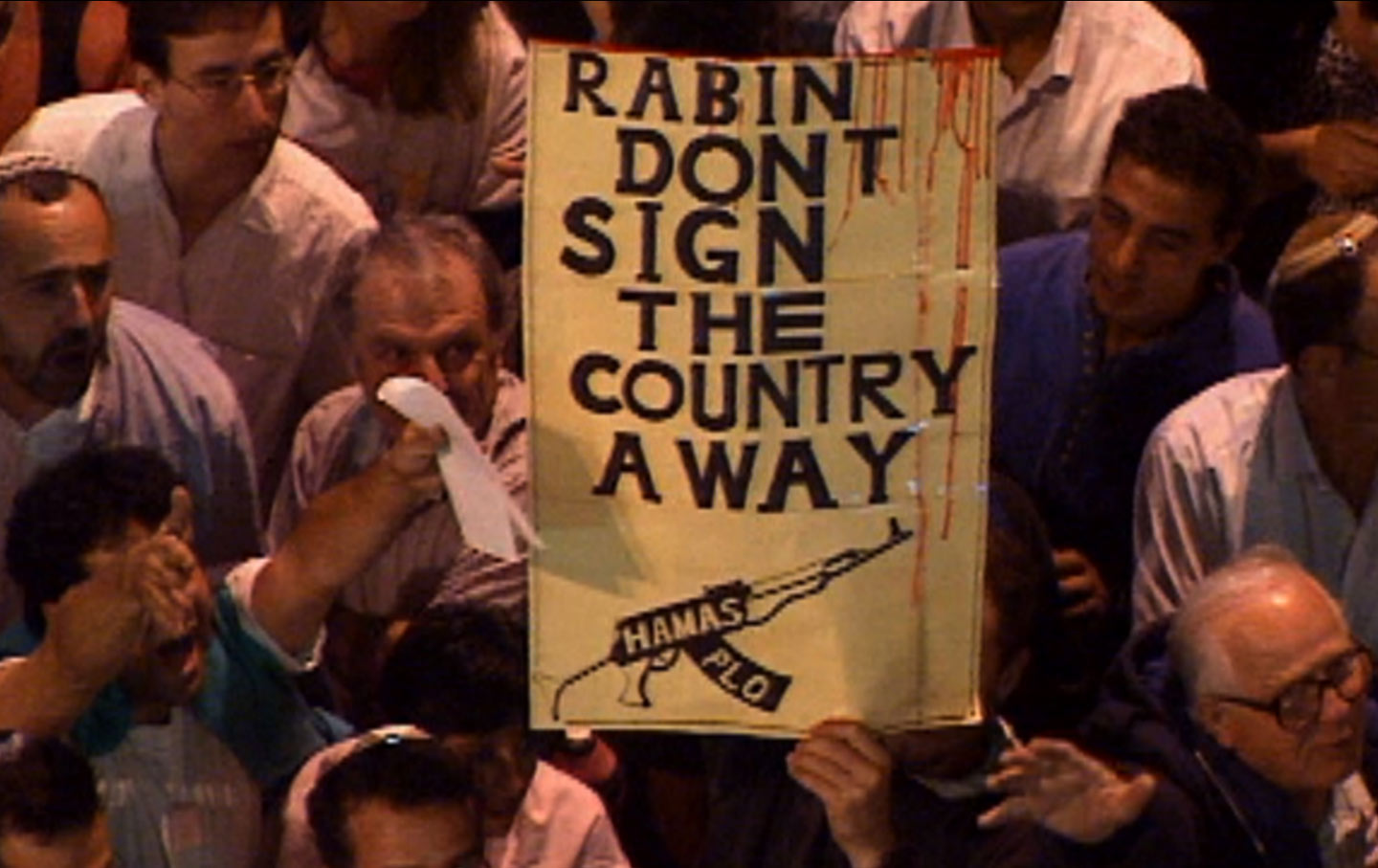

A scene from Rabin, the Last Day.(Kino Lorber Inc.)

It was the most politically effective assassination in modern history. On November 4, 1995, a young man named Yigal Amir, steeped in the messianic zeal of Israel’s religious right and the settler movement, killed Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, punctuating with three gunshots the aftermath of a mass rally in Tel Aviv. The central square had overflowed that evening with joyous supporters of Rabin’s policy of exchanging occupied territories for peace with the Palestinians—a policy that was literally anathema to Amir and others in his camp. In the weeks before the attack, they had chanted furiously in the streets for the death of the “traitor” prime minister, parading with a coffin bearing an effigy of Rabin dressed as a Nazi. You might have imagined, in the days after the murder, that a large portion of the Israeli public would recoil from this virulent rejectionism, which Benjamin Netanyahu and his Likud party had not merely countenanced but helped to incite. Israel’s internal violence had been exposed; the peace movement that Rabin had animated, and for which he was now a martyr, would surely gain strength. Yet the rejectionists were not rejected.

The very next year, Netanyahu was elected prime minister. The Israeli left slowly withered, and so did the negotiations with the Palestinians, which after 2001 came to receive only lip service and then (in Netanyahu’s 2015 campaign) not even that. By the 20th anniversary of Rabin’s murder, members of the religious right were in powerful cabinet positions, illegal settlements were burgeoning, and the prime minister had publicly sworn that the Palestinians would remain stateless so long as he was in office. Yigal Amir had gotten everything he’d wanted, short of the Messiah.

To understand how the assassin was handed this success, you cannot limit yourself to compiling a disheartening list of events. You also have to get under the skin of people’s attitudes and beliefs and comprehend why the Israelis responded to the unfolding events as they did. It’s more than you can expect to learn from any one film, however thoughtful and complex. But maybe you can get somewhere by watching two new films: Amos Gitai’s Rabin, the Last Day, and Joseph Dorman and Oren Rudavsky’s Colliding Dreams.

The first, in characteristic Gitai fashion, is a politically outspoken but formally disjunctive work that doesn’t pretend to be a documentary, despite being based on piles of official documents. It’s more like a kaleidoscopic essay that juxtaposes “actualities footage,” sober re-enactments, and moments of outright playacting, often blurring the lines among them. The second film is a much more straightforward project, which blends wide-ranging interviews, archival images, and voice-over narration into a smooth historical account. Gitai plunges you intensely into one brief period, from the weeks of agitation leading up to the assassination through the end of the ensuing investigation. Dorman and Rudavsky take a panoramic view of Zionism as a whole, sweeping from the Pale of Settlement in the 1880s to today’s Israeli settlements in 135 minutes. Neither film explicitly asks why the peace movement collapsed after Rabin’s assassination; but taken together, the two might advance you toward an answer.

Rabin, the Last Day opens with a prologue that serves as both advertisement and warning for the experience to follow. An interview that Gitai recently conducted with former Israeli president Shimon Peres gives way to news footage of the November 4 rally and then to a re-creation of the video that captured the assassination, the latter images jumping without transition into a dramatization of the action inside Rabin’s car, with a bodyguard frantically compressing the prime minister’s chest and blood spurting everywhere. You see very quickly the different materials Gitai will use; you prepare to be wrenched from a helicopter shot to a claustrophobic close-up, from measured conversation to frenzied shouting, from fact to not-quite-fiction. As if this weren’t enough to pull you in, and at the same time knock you back on your heels, Gitai follows this opening sequence with a second prologue, acted out on a gloomy set of uncertain, dreamlike dimensions. Three elder statesmen pore over documents, the actual video of the assassination plays repeatedly on a screen, and two lawyers for the commission of inquiry take testimony from the man who recorded the images. The camera travels slowly across this imagined scene and then glides back again, covering a lot of ground but, like the inquiry itself, getting nowhere.

By now you might already be exhausted—but Gitai is just getting started. Moving into the core of his film, he cuts back and forth between re-enactments of the commission hearings and dramatizations of the lives of Yigal Amir (Yogev Yefet) and others on the Israeli far right. You see scenes of scruffy young settlers setting up a trailer near Hebron and later being dragged away by Rabin’s army; an ultra-Orthodox group conducting a ceremony to curse Rabin; a psychologist delivering her diagnosis—absolutely unquestionable—that Rabin, God help us, is schizophrenic and utterly cut off from reality; a rabbi, charged with the education of Amir, darkly instructing his pupil to study a passage of the Talmud concerned with justifiable homicide and then draw his own conclusions. Speaking at the screening of Rabin, the Last Day at the 2016 New York Jewish Film Festival, Gitai praised the restraint of his actors’ performances; but in the scenes depicting the right-wingers, his judgment can be understood only within the normative range of Israeli behavior. The subtle actors do everything short of tearing out their hair while banging their heads on the furniture.

The only performers who seem self-possessed to American eyes play the commissioners heading the inquiry and their legal counsel—and even they have a heated moment, when the lawyers argue that the occupation’s effects are relevant to the investigation, and the commissioners refuse to consider evidence on that subject. Their body, the commissioners insist, is authorized to examine nothing but the role of the security forces and the police—to determine, for example, how the gunman had been allowed to linger unmolested near the prime minister’s car for 40 minutes. Any nonoperational matters are out of bounds.

With that ruling, you come to the crux of Gitai’s argument in Rabin, the Last Day and also to an explanation for his method: The inquiry, in his view, deliberately split the how from the why, the crime from the community in whose interests the criminal acted. The film’s fragmentation imitates that rupture.

There is precedent for this procedure, in Francesco Rosi’s Salvatore Giuliano—and although it’s unfair to compare any film to that masterpiece, I think Gitai is admirable for following its tradition of critical, investigative moviemaking in his own rough-and-ready style. At once immediate and distanced in method, dramatic and discursive, his film confronts you with evidence of a widespread, willful blindness in Israeli society that may be even more troubling today than it was in 1995.

What Gitai cannot do, given his relatively tight focus on the investigation, is to put that willful blindness into historical context. For that, you have to turn to Dorman and Rudavsky and their Colliding Dreams.

It’s as good a feature-length history of Zionism as we’re likely to get: judicious, sophisticated, attentive to a range of viewpoints (both Israeli and Palestinian, as the title suggests), and free from teleology. Among the interview subjects are a few people—representative types—who believe that God created Zionism to return the Jews to their promised land, or that European colonial powers invented Zionism to dispossess the Palestinians; but the majority of the speakers, like the filmmakers themselves, understand that nobody was in charge of the developments that led to the State of Israel, nor did anyone foresee all of the consequences.

Which is not to say that the historical process, undirected and indeterminate, has relieved the Israelis of moral burdens, or made the Palestinians’ reality more acceptable.

Here, though, is how it happened, starting from the time when the majority of the world’s Jews, living as a people apart in multi-ethnic European empires, had no territory they could claim as their own and little hope of being accepted by the nationalist groups rising around them. Even before the advent of Theodor Herzl and the project for a Jewish state, Jews were fleeing to Ottoman Palestine, a place with which they felt an ancestral bond, and where they believed they could throw off their humiliation and subservience like an outworn caftan and emerge as a free people. As Kobi Sharett, the son of a former prime minister, recalls for the camera, an early Zionist delegation reported that the land was like a beautiful young woman, endowed with everything you could desire. The only problem, the report added, was that she was already engaged. Or as the activist and journalist Orly Noy puts it more harshly, the Jews jumped out of a burning building and onto somebody’s head.

You hear from some of the people who’ve been jumped on: academics and political figures including Hanan Ashrawi, Sari Nusseibeh, Khalil Shikaki, Saman Khoury, and Said Zeedani, as well as various unnamed Palestinians interviewed in West Bank cafés. You also hear from Jewish Israelis, such as the historian Gadi Taub, whose forebears came to Palestine despite everything, for the unchallengeable reason that they simply had nowhere else to go.

Where Colliding Dreams excels is in tracing the ideologies, ideals, aspirations, and fantasies that these Jews brought to their place of refuge and developed over time. A fascination with biblical archeology helped their imaginations leap backward over rabbinic Judaism, and centuries of living in Europe, to an ancient time and a mythical kinship with the land. An early period of mingling comfortably with their Arab neighbors, sharing in their communal life and adopting their ways, enabled the new arrivals to ignore that they were starting to push sharecroppers out of their homes. In the words of the political scientist and former Jerusalem deputy mayor Meron Benvenisti, this economic displacement was “peaceful violence” but violence nonetheless. And many of the Zionists, caught up in their struggle for existence, could not permit themselves to see it.

Out of everything that might be learned from Colliding Dreams—and there’s a lot—perhaps the most useful lesson is that Israel’s willful blindness dates back at least a century. You spot it at the source in Dorman and Rudavsky’s film, sense the gathering strength of its current, follow its widening course through generations. And in Gitai’s film, you watch its floodwaters wash away any possibility of a public accounting for the murder of a head of state. Why did the peace movement collapse and the left wither? Because too many Israelis—and not just on the right—were used to ignoring what was in front of their eyes. Gitai, Dorman, and Rudavsky make you look.

* * *

Ride along, if you will, through the rustic 19th-century world of Radu Jude’s Aferim!, a place that is nostalgically welcoming for moviegoers who long for wide-screen black-and-white entertainment, but less reassuring for those who contemplate the worldview of its main character, Costandin. Played by the veteran Romanian actor Teodor Corban, he is a Wallachian constable—which is as much as to say, a bounty hunter—with a handlebar mustache, embroidered jacket, and iron-lunged bluster. Costandin endlessly bullies (or, in his mind, instructs) his reedy son and apprentice Ionita (Mihai Comanoiu), extorts bribes on all sides, swills booze, frequents prostitutes, deprecates everyone he encounters (to their faces if they’re peasants, behind their backs if they’re not), and likes to reminisce about the best times he ever knew: when he was a soldier and killed left and right.

The tale of the pursuit of a runaway slave (Toma Cuzin)—one of the Roma, commonly and dismissively called “crows,” who were held as property by the landowners and monks of Wallachia—Aferim! is a landscape film of gorgeous variety, which sends Costandin and Ionita riding through mountains, fields, and forests, and a folkloric romp of increasingly grisly tone. The terrain that Costandin and Ionita must negotiate is an obstacle course of stony roads and impassable waterways, the social structure a maze of feudal possessions, and the mentalities a poisonous web spun of spite and ignorance. At first, these low thoughts are so outlandish, and their thinkers so outspoken, that you can laugh at them, as when a priest—one of the film’s better-educated characters—improves Costandin’s journey by cataloging for him the different inherent vices of all the peoples of Europe. By the time you get to a market, where the bounty hunters catch the cruelest Punch and Judy show you’ve ever seen, the pervasive brutality is no longer so funny. At the climax, when the slave Carfin falls back into his owner’s hands, the violence becomes unspeakable and yet is accepted by everyone—except, it seems, by Costandin, who voices the most tentative and subservient of demurrals before going along like the rest.

And yet, it’s not the bloodshed that makes the conclusion of Aferim! so horrifying. It’s the helpfulness of one of Carfin’s fellow slaves, who steps forward to offer the landowner a better tool for his job. Costandin has, as it turns out, the gentlest conscience in the movie.

Stuart KlawansStuart Klawans was the film critic for The Nation from 1988 through 2020