Black women have made connections between their struggles and those of black men since the 1800s.

Paula J. Giddings

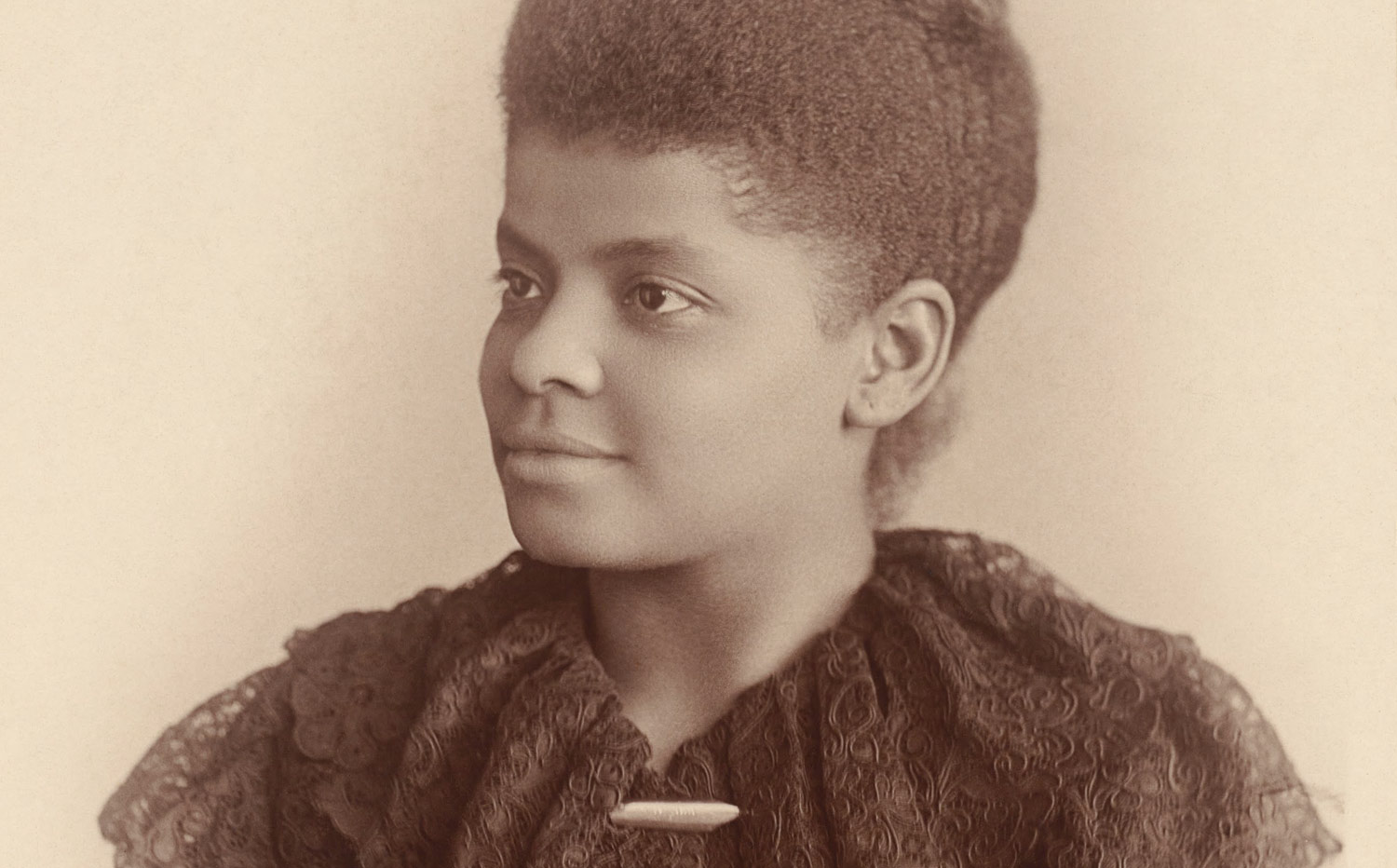

Ida B. Wells, c. 1893.

Although African-Americans have made unprecedented progress in terms of politics, business and access to elite institutions, other developments suggest that something else is going on. Voting rights are being curtailed, communities are deteriorating, and incarcerations for minor and even fabricated criminal charges are on the rise. Most troubling is the news of cold-blooded murders committed against them in the public square, too often with impunity.

It sounds as though I’m describing our current landscape, but in fact this is an apt description of the late nineteenth century, when African-Americans occupied political offices, accumulated wealth and held administrative positions that would not have been dreamed of a generation before. But this was also the era of the literacy test, congealing segregation and the convict-lease system, which provided the black labor forfeited by emancipation. By the 1890s, newspapers disseminated the details of two, three, sometimes four lynchings each week to a national audience.

As is true with the current generation, nineteenth-century black activists struggled against the complacency of those who believed that the progress of the few would trickle down to the many—not through agitation, but by the mere acquisition of education, wealth and middle-class values. When criticized by earlier generations, they—like Mychal Denzel Smith in his essay—pointed to the important and inspiring youth work that was being done, and touted their generation’s more progressive views of women, who were making gains in education, community “uplift” work and newly formed women’s organizations.

But it was also true that black women, who had wielded significant influence during Reconstruction, were losing political ground to men, who attempted to marginalize them in the separate sphere of women’s work.

It was the rise of lynching that put black women at the center of anti-racist work. Although the largest number of victims were young black men accused of raping white women, black women like Ida B. Wells—who led the first anti-lynching campaign back in 1892—pointed out that women were lynched too, and that the stereotypes of hypersexuality and immorality that were getting black men killed were deeply connected to stereotypes of black women that kept them vulnerable to sexual predation and devalued them as persons. With the understanding that racial violence against men was also a women’s issue, and that violence against women was both a race and gender issue, black women made anti-lynching activism a central tenet of their organizations long before the NAACP was founded.

Nevertheless, the role of black women in racial-justice work is always contested and, during most of the civil-rights years, remained largely the prerogative of men. But it is also true that the connection between the struggles of men and those of women remained alive and well. The most important lesson of the Rosa Parks story is that she began her career as an anti-rape activist in the Alabama of the 1940s and that the men and women within her circle formed the nucleus of the 1955–56 Montgomery bus boycott that transformed the nation. On the mind of Parks and other activists that year was not only the murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till—lynched in Mississippi for purportedly whistling at a white woman—but the travails of 15-year-old Claudette Colvin, who had been arrested for refusing to relinquish her seat on a Montgomery bus nine months before Parks was. Colvin’s pioneering effort was undermined by the fact that she was poorly educated and later visibly pregnant even though she was unmarried (and thought to have been sexually “used”). The struggles and consciousness of both black men and women became the catalyst for what many consider the greatest and most far-reaching movement in the nation’s history.

In the twenty-first century, we feel much like our forebears must have felt when they read about the frequent lynching and incarceration of black youth. But these days, the martyrdom of Trayvon Martin, Jordan Davis and Michael Brown has been understood as a crisis that only men face. Only black boys are deemed endangered and deserving—and black girls are again pushed to the margins. First codified by the 1965 Moynihan Report, which claimed that the pathology of the black family was due to emasculated men and strong women, this troubling disconnection is now writ large in public policy. The White House’s signature race initiative, My Brother’s Keeper, promises $300 million to help boys of color—but not girls.

Every generation has its own unfinished work to do. It is time for a twenty-first-century anti-lynching campaign. Read more from our special issue on racial justice

Mychal Denzel Smith: “How Trayvon Martin’s Death Launched a New Generation of Black Activism”

The Editors: “Renewing the Struggle for Racial Justice, Post-Ferguson”

Rinku Sen: “As People of Color, We’re Not All in the Same Boat”

Dani McClain: “Obama’s Racial Justice Initiative—for Boys Only”

Frank Barat: “A Q&A With Angela Davis on Black Power, Feminism and the Prison-Industrial Complex”

Melissa Harris-Perry: “Obama Is Responsible for the Protests in Ferguson—but Not in the Way You Think ”

Paula J. GiddingsPaula J. Giddings, a professor of African-American Studies at Smith College, is the author of Ida: A Sword Among Lions.