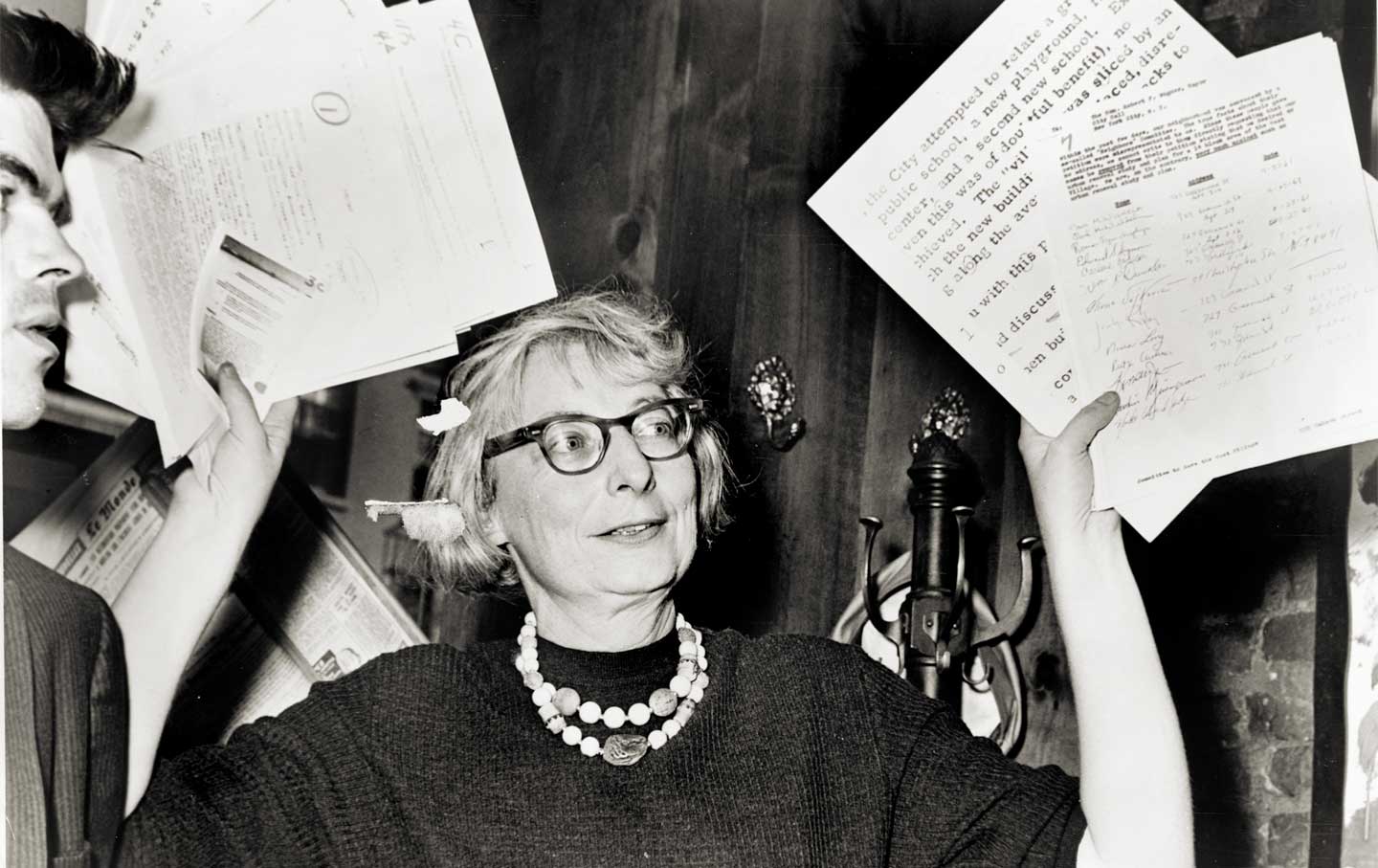

Jane Jacobs in 1961.(World-Telegram & Sun photo by Phil Stanziola. Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

In 1956, Jane Jacobs was 39 years old, working as a staff writer at Architectural Forum. Her boss, unable to attend a conference at Harvard, asked her to go in his stead and give a talk on land banking. Jacobs, skittish about public speaking, reluctantly agreed, on one condition: that she could speak on a subject of her choice.

That subject, it turned out, was the utter wrongheadedness of many of the ideas cherished by her audience, the era’s luminaries of urban planning. The prevailing wisdom at the time held that “urban renewal” required clearing “slums” and starting over. The rebuilt cities would tidily disentangle residential and commercial areas and include plenty of open space. These ideas may have looked good in architectural drawings, but in real life, Jacobs had come to believe, they were a formula for lifeless monotony.

In East Harlem, she noted, 1,110 stores had been razed to make way for housing projects. Jacobs argued that these little shops couldn’t simply be replaced by supermarkets. “A store is also a storekeeper,” she said. Stores were not just commercial spaces; they were also social centers that “help make an urban neighborhood a community instead of a mere dormitory.” Even empty storefronts had a function, often sprouting into clubs, churches, or hubs for other civic activities. When these spaces were destroyed, the community was gravely wounded.

This speech, a turning point in Jacobs’s career, appears in Vital Little Plans, a new collection of her short works; Robert Kanigel’s new biography of Jacobs, Eyes on the Street, fills in the context. The men in the room—including the mayor of Pittsburgh, the head of the New York City Housing Authority, and The New Yorker’s architecture critic, Lewis Mumford—took the rebuke remarkably well, and Jacobs won some distinguished admirers. The speech was also the germ of what became her masterpiece, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), one of the seminal books of the 20th century.

The talk demonstrated Jacobs’s trademark strengths: her clear-eyed vision, her pungent language, her sheer gutsiness (she may have dreaded public speaking, but she never hesitated to tell her betters what she thought). It also reflected her slippery political orientation. Jacobs was celebrating commerce and condemning government overreach in the form of public housing, and thereby showing some sympathy with the values of the right. Yet she was doing so on behalf of low-income people who, she believed, had been ill served. Like any good leftist, she was defending the underdogs: the mom-and-pop stores as well as the residents of these projects, many of whom hated their bleak housing as much as she did.

Jacobs’s unconventional politics grew out of her temperament. She was allergic to dogma; she followed not an ideology but a methodology. She did not assume, or imagine, or take things on faith; she observed. But she didn’t stop there: She accumulated observations and distilled them into general principles. For her, empiricism and theory were not opposites but complements.

Jacobs hinted at this approach near the end of her talk: “the least we can do is to respect—in the deepest sense—strips of chaos that have a weird wisdom of their own not yet encompassed in our concept of urban order.” Her great accomplishment would be to translate that “weird wisdom” into terms we could all understand.

* * *

Jane Jacobs was born in 1916 with a decidedly less euphonious name—Jane Butzner—in the coal town of Scranton, Pennsylvania. The third child of a doctor and a teacher, she was delivered by her own father. In her childhood home, her parents encouraged her inquisitive mind and accepted her rebellious streak. Jacobs read widely, wrote poems, and held imaginary conversations with interlocutors like Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin.

Despite her precocity—or more likely because of it—the young Jane was never a good fit for school. She barely made it through high school and, instead of college, took a course in stenography. Her parents had instilled in her the importance of both learning a practical trade and pursuing her calling, which she determined early on would be writing.

In 1934, during the depths of the Depression, Jacobs moved to New York, where she lived with her elder sister Betty in Brooklyn Heights. In the mornings, she took the subway to Manhattan to interview for secretarial work; in the afternoons, she wandered around the city. On one outing, she discovered Christopher Street in Greenwich Village and promptly informed Betty that they’d be relocating to that neighborhood.

After working briefly as a secretary, Jacobs enrolled in Columbia University’s extension school. Liberated to pursue her interests, she excelled in her classes—geology, economics, chemistry, constitutional law—though she never earned a degree. Around this time, Jacobs got her first break as a writer: a series of freelance assignments for Vogue. Each of these four pieces, collected in Vital Little Plans, explored a different New York industry—fur, leather, flowers, diamonds—and the neighborhood in which it thrived.

This period was followed by a succession of staff jobs: at Iron Age, a trade journal where she covered such scintillating topics as the role of nonferrous metals in the war effort; at Amerika, a propaganda magazine published by the US government and distributed in the Soviet Union, for which she started to cover urban planning; and finally at Architectural Forum.

Her personal life, meanwhile, replicated the happy stability of her childhood. In 1944, she married Bob Jacobs, a handsome architect with whom she’d have three children and enjoy a long, devoted partnership. In 1947, the pair bought a fixer-upper on Hudson Street for about $7,000. When Jacobs took the job at Architectural Forum, her husband helped her learn how to read drawings and blueprints.

Covering urban renewal for the magazine, Jacobs was initially supportive (or, as she would come to believe, insufficiently skeptical) of the ideas on which it was based. In the abstract, they had a certain internal logic. But as she reported more deeply, she began speaking with people who questioned that logic, and she noticed more disjunctions between the claims and the reality. She gradually formed her own strong opinions, and as she started to express them, she emerged fully as a writer. By the time she published her most celebrated book, she was a masterful polemicist.

Death and Life’s first sentence didn’t mince words: “This book is an attack on current city planning and rebuilding.” The heart of the work was arguably “The Conditions for City Diversity” (Part II out of four), in which she laid out the arguments that would become canonical. Against the planners who sought to neatly divide a city’s neighborhoods by use—residential, commercial, industrial, and so on—Jacobs advocated the opposite: “mixed primary uses,” or homes and stores and restaurants and offices all in close proximity. In such areas, different people were on the street for different reasons at different times of day, contributing to the vitality of the neighborhood, attracting new enterprises in a virtuous circle, and providing a continuous stream of “eyes on the street” to keep it safe.

Jacobs also advocated short blocks, with frequent opportunities for turning corners, as opposed to the “superblocks” loved by planners; buildings of different ages and conditions, in order to support a variety of ventures, including more experimental ones; and residential density, which had heretofore been seen as unwholesome congestion. All of this was conveyed in prose that was sometimes caustic, sometimes aphoristic, and always exceptionally lucid and vigorous.

After this section, Death and Life continued for another 10 chapters, discussing the “self-destruction of diversity” (what we would now call “gentrification”); “unslumming and slumming,” her pithy terms for neighborhood regeneration and decline; proposals for subsidized housing; and recommendations to “salvage” the housing projects she abhorred. It was an astoundingly ambitious book, laying down general laws drawn from sharp observation, with a healthy dose of detailed policy suggestions revealing an alertness to the practical challenges.

If Jacobs’s Harvard speech made her name in planning circles, the book launched her into broader renown. As Kanigel chronicles, The New York Times proclaimed it “a huge, a fascinating, a dogmatically controversial book.” The Wall Street Journal declared: “In another age, the author’s enormous intellectual temerity would have ensured her destruction as a witch.” But the praise wasn’t unanimous. The sociologist Herbert Gans, as well as other reviewers, pointed out several blind spots. Jacobs championed a very particular urban ideal—defined by vitality and diversity—that had no room for other virtues, such as tranquility and natural beauty. Gans also charged her with succumbing to the “physical fallacy”: overestimating the importance of factors like block length and store locations, and underestimating those like ethnicity and culture. Meanwhile, her erstwhile admirer, Lewis Mumford, wrote a New Yorker piece offering some restrained praise but also some acerbic criticism, calling the book “a mingling of sense and sentimentality, of mature judgments and schoolgirl howlers.” (His hostility may have had something to do with the fact that, despite his earlier support, Jacobs—a stranger to sycophancy—had in Death and Life called one of his books “morbid and biased.”)

* * *

During this time, Jacobs not only elucidated her vision of the good city; she invested prodigious energy in making it a reality—or, rather, in staving off its annihilation. Her Greenwich Village neighborhood found itself repeatedly embattled, threatened first by Robert Moses’s plan to ram a highway through Washington Square Park; then to designate the West Village a slum and clear it for an urban-renewal project; then to destroy nearby neighborhoods for his proposed Lower Manhattan Expressway.

Jacobs participated in and sometimes led the protests that succeeded in halting each of these plans. She and her neighbors did all the classic grunt work of community activism: making calls, writing letters, drawing up petitions, organizing rallies. Sometimes they dispatched their children to hang posters and gather signatures. Jacobs recalled that during the fight to save the West Village, “we just disconnected the doorbell and left the door open at night so we could work and people could come and go.”

From these skirmishes, Jacobs learned crucial strategic lessons. One was that the neighborhood had to fight even the early exploration of a “slum” designation, because the label would scare off businesses and home buyers, becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy. Another lesson, imparted by a sympathetic federal-housing official, was that the community should never express any affirmative desires, which would allow city officials to claim they’d received the residents’ input, but rather should focus single-mindedly on blocking the plans it opposed.

Though Jacobs proved herself a skillful activist, she never wanted to become one, seeing it as a distraction from her real work: writing. “I resented that I had to stop and devote myself to fighting what was basically an absurdity that had been foisted on me and my neighbors,” she once told an interviewer.

In 1968, Jacobs and her family moved to Toronto, primarily so that her two sons could escape the draft for the Vietnam War. But there, too, some of the same misguided views about urban planning were ascendant. No sooner had she settled in Toronto than she was fighting another expressway slated to be carved through her new neighborhood. Using the chops she’d acquired in New York, Jacobs helped to defeat the plan. Her presence was welcomed in her adopted city, where she became an éminence grise of urban planning.

Though Jacobs never repeated the sensation caused by her debut, Kanigel is at pains to stress that she was no “one-book wonder.” The Economy of Cities (1969) and Cities and the Wealth of Nations (1984) further developed some of the themes of Death and Life, with greater historical breadth. They advanced arguments that seem startlingly relevant, if almost clichéd, today: Successful cities are hubs of innovation, the real economic engines of nations; and places that fail to innovate—whether declining cities or rural towns—risk stagnancy and alienation. Her last book, Dark Age Ahead (2004), foresaw the disastrous bursting of the housing bubble that was swelling at the time.

To generate her ideas, Jacobs read deeply and idiosyncratically. As Samuel Zipp and Nathan Storring write in their excellent introduction to Vital Little Plans, “Jacobs tended to look at history the way she did a cityscape. She scouted around for promising examples of individual phenomena, situations in which city or economic life seemed to have been working, and then sought to understand the processes that organized these data into constructive systems.” At times, her bold hypotheses got a bit too far ahead of the evidence. A provocative theory that agriculture had its origins in cities risked appearing to reflect her pro-urban outlook as much as the historical record. (Her faith in cities was perhaps the closest she came to an ideology.) This sort of work strayed from her core strength: proceeding from close observation to general principle to practical application. On the other hand, one of her ideas—that the agglomeration of diverse industries could facilitate innovation—was plucked from relative obscurity and endorsed by the economist Robert Lucas, who would later win the Nobel Prize. Economists now call this phenomenon “Jacobs externalities.”

* * *

In the years since her death in 2006, at age 89, Jacobs has been routinely hailed as a heroine, both for her unmatched influence on our understanding of cities and for her role in helping to defeat many of Moses’s plans for New York. But her work has also been the target of criticism—partly because of her political heterodoxy, and partly as a reaction to her canonical status.

The criticisms often boil down to claims that Jacobs failed to sufficiently take into account the need for affordable housing or the threat of gentrification. Some even suggest that her work is partly responsible for gentrification, thanks to her celebration of neighborhoods like the West Village (where her old home was sold for $3.3 million in 2009).

But before accusing Jacobs of these oversights, one is advised to read her very thoroughly. A chapter midway through Death and Life, “The Self-Destruction of Diversity,” offers as good a description as any of the process by which quirky neighborhood enterprises get priced out and replaced by banks and insurance offices. Jacobs advances several policy solutions, including “zoning for diversity”: that is, limiting the proliferation of the same kinds of businesses and buildings—the reverse of the more usual purpose of zoning.

As for affordable housing, Death and Life explored in exhaustive detail a plan that Jacobs called the “guaranteed-rent method.” She proposed that housing would be created by private developers and landlords, and that the government would subsidize rents. For new construction, an “Office of Dwelling Subsidies” would guarantee the necessary financing to the builders. Tenants would be selected from applicants from a designated area. If their incomes rose, the subsidies would drop. But no level of income would be disqualifying, because Jacobs recognized the psychological implications of income-restricted housing: It caused a residence to become stigmatized and synonymous with failure. If nobody wanted to stay—if success meant getting out—it would struggle to become a vibrant or desirable place to live. This chapter is wonky and dense, and because it comes toward the end of a very long book, it’s easy to overlook, but it belies the caricature of Jacobs as an elitist libertarian.

Her attitude toward government, based on what she saw at the time, was that it could stifle as often as nourish the organic flourishing of cities and their residents. But Jacobs wasn’t against government intervention per se; nor was she against planning. She favored policies that she believed would foster life in cities, and she favored certain kinds of plans—namely, little ones. She acknowledged that some plans had to be far-reaching—a subway system, for example—but, as a rule, “Little plans are more appropriate for city renewal than big plans.” In a 1981 speech in Germany, she argued that big plans by their nature tend to be boring and lacking in visual diversity because they’re “the product of too few minds.” What’s more, big plans tend to foreclose possibilities: They’re inflexible, and “when the plans are very big the mistakes can be very big also.” After all, she concluded, “Life is an ad hoc affair.”

Today, Jacobs has not only bequeathed us a legacy of great ideas; she can also serve as an exemplar of how to approach our own formidable problems, in urban planning and beyond. To follow her lead is to look closely to determine what works and what doesn’t. It is to nurture a multitude of little plans and, not least, to do all we can to stop big plans based on bad ideas.

Rebecca Tuhus-DubrowRebecca Tuhus-Dubrow is the author of Personal Stereo, a cultural history of the Walkman.