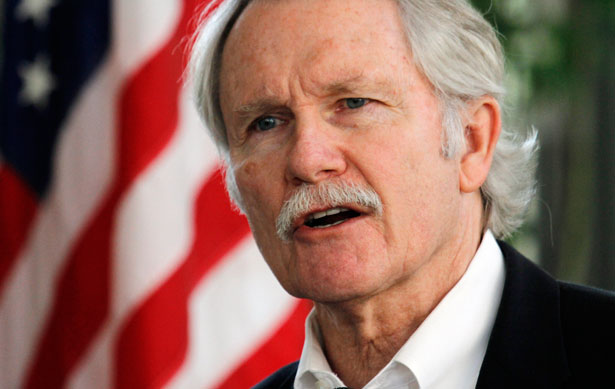

Oregon Governor John Kitzhaber. (AP Photo/Don Ryan, file)

Oregon Governor John Kitzhaber is sitting in a second-floor conference room in downtown Portland’s World Trade Center, explaining the raft of education and healthcare reforms he’s pushing. He’s wearing his signature pressed blue jeans, brown tassled loafers, a white shirt, purple tie and dark blue woolen sports jacket. His gray hair is neatly combed, his mustache carefully trimmed. When he wants to illustrate a policy point on healthcare, he gets up, strides over to a white board and draws a graph showing the trade-offs between the willingness of doctors to absorb economic risks and the amount of time they spend on each patient.

It’s mid-February. The next week, the governor will receive notice that his state is one of six to be awarded a prestigious State Innovation Model grant, worth up to $45 million, by the federal Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation, which was established under the Affordable Care Act. Oregon received the grant because of the reforms Kitzhaber’s administration has pushed regarding delivery of medical services.

In healthcare, Kitzhaber’s goal is to provide a financial incentive to doctors and hospitals to pursue less expensive diagnostic and treatment models, and to spend more time cultivating preventive and primary care relationships with patients. In education, it’s about encouraging educators, parents, students, healthcare providers and community institutions to work together to improve outcomes, rather than simply getting kids into the classroom and letting inertia take over. In both cases, it’s about recalibrating priorities. The governor, who’s known for approaching complex policy problems with the technical precision of an engineer, suddenly quotes the Roman philosopher and statesman Seneca: “No wind’s the right wind if you don’t know what port you’re sailing for.”

This is a story of focus, of a push by Oregon’s third-term governor (he held the job from 1995 to 2003 and was re-elected in November 2010, as the state struggled to overcome recession and fiscal crisis) to reinvent the way that government delivers core services, especially in healthcare and education. His aim is that, by 2025, 40 percent of the state’s high school students will go on to attend four-year colleges, 40 percent will attend community colleges, and the remaining 20 percent will graduate from high school or get an equivalency degree. Integrated funding mechanisms—some in place, some still under development—will back up these aspirations, and long-term timelines for reform will, the governor hopes, ultimately make Oregon’s population better educated and healthier.

Kitzhaber has particular credibility on these issues: he’s not only a three-time governor but a former legislator and emergency-room doctor. He has earned a national reputation for thinking holistically and eliminating compartmentalized policy and funding silos that ought to be dealt with as parts of a continuum. In all likelihood, that was why he was invited to sit in Michelle Obama’s box during the 2013 State of the Union address; soon afterward, he was addressing the National Governors Association about his reforms.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →Only slightly tongue-in-cheek, Kitzhaber introduced into our conversation his grandiosely named Unified Theory of Everything. “The pathway to the American Dream,” he argues, in an e-mail he sends me shortly after we meet, “revolves around a job for which the individual is paid a living wage—enough to meet their basic needs—and an opportunity for upward income mobility. To create that pathway our public institutions (government) and our economy must be aligned around the same goal: to ensure an equal opportunity for all Americans to achieve their shared aspirations.” For Kitzhaber, poverty and ill health are too often the result of inadequate education; fixing these problems is what he calls the “left side” of his unified theory. On the right side, he talks about the need to invest in clean technologies and renewables, to open routes to prosperity that neither denude the environment nor leave millions unemployed.

Over the past two years, Kitzhaber has focused mainly on the left side of his equation, pushing through the Oregon legislature—which was almost evenly split between Republicans and Democrats from 2011 to 2012—an extraordinary raft of reforms, with bipartisan cooperation, and setting in motion an ambitious overhaul of healthcare and education. “How do you finance public education, and make sure that the system of public education is actually producing the outcomes that you want?” the governor asks. “It’s very, very clear that the greatest inequities and disparities in our country are among the poor, communities of color and English-language learners. Those kids often arrive at kindergarten with a large achievement gap. And many of them are not able to overcome that. The pathway up is early childhood—making sure that every child arrives at the classroom in kindergarten ready to learn.”

Kitzhaber has pushed the legislature to spend more on education in a drive to improve poorly performing schools. As his healthcare savings kick in, he hopes to add to those totals. And he isn’t just talking about K–12, but what he calls a “0–20 strategy.” In fact, it starts before birth, with prenatal counseling, and involves better nutrition programs, parenting classes and medical clinics in school settings. He wants to prepare all kids for kindergarten, have them reading at grade level by third grade, and get middle school kids ready for high school. He wants high school kids taking community college and university classes. Kitzhaber’s integrated model continues all the way through graduate school.

Underlying these aspirations are a series of “achievement compacts” the state has signed with local school districts, colleges and universities, with a number of financial carrots to encourage better teaching. “Ultimately,” argues Ben Cannon, the governor’s education policy adviser, “it’s about a desire to create a truly seamless experience for students and their families. The state’s role is principally to establish the budget and desired outcomes, and empower regions and communities to deliver those outcomes.”

Schools that meet those standards are labeled “model” schools, and are essentially given the funds and space to pursue their specialized projects. Those with poor success rates are categorized as “focus” or “priority” schools; the state assigns them “coaches”—retired administrators and other education specialists—who work with the principal and teachers to improve administration and classroom methods.

The Oregon Education Investment Board, created in 2011 by the State Senate and responsible for coordinating these initiatives, is planning investments on innovative programming that could range as high as a couple hundred million dollars annually; the exact amount is being negotiated by the legislature. This is out of a total education budget of roughly $8 billion. The grants are intended to reward pilot projects that are finding the quickest ways to reach the new goals. The hope is that these investments will have magnifier effects on the broader system. “This industry, its greatest currency is relationships where people share knowledge, expertise and common interests,” says Rudy Crew, the erstwhile New York City schools chancellor hired by the governor last July as the state’s chief education officer. “But can they share when they’re not on each other’s natural dance cards? That takes more orchestration. I meet with the superintendents, go to their meetings, go to their homes. This is a campaign; this is not just a casual set of comments.”

These days, for example, it’s no longer enough for community colleges or universities to have lots of students enrolled in classes and picking up credits; now their graduation rates will be under the microscope. Ultimately, their funding levels will depend on graduation numbers.

* * *

The education reform team knows that all of this involves extraordinary collaboration between teachers and students, parents, healthcare providers, nutrition experts, local libraries and businesses. And they’re going all out to bring every party to the table. “You’ll have a major shift this year,” Crew says. “You’ll start to see the culture change this academic year.”

At the Gladstone Center for Children and Families (GCCF), half an hour’s drive south of Portland, the early-childhood pieces of the puzzle, on which all these other hopes rest, are already falling into place. There, in a converted 1960s Thriftway supermarket bought by the school district at a hefty discount back in 2005, more than 180 kids are concentrated in a stand-alone, full-day kindergarten, whose capacious windows look out onto fields and evergreen groves. Eighty local preschoolers also show up for Head Start sessions. And local families regularly attend afternoon and evening story times. Young adults attend parenting classes, and Clackamas Community College runs GED classes for Spanish speakers.

The classrooms, ranged along a central hallway, are spacious, with kids seated around six-sided wooden tables, their art lining the walls. Outside is a playground centered around a large red, yellow and blue climbing structure. Off to its side is a garden, which kindergartners plant in the spring, leaving the harvest to next fall’s incoming class. At the far end of the campus, a medical clinic offers pediatric services, adult medical checkups, shots and mental health referrals. There are two dental clinics in the area, to which campus doctors refer patients. And in a nearby building, WIC vouchers are provided as a part of the hub of onsite services offered through the GCCF.

There are comprehensive education and healthcare centers in other states, but mostly they operate in charter schools. Gladstone is unique for having so fully incorporated such a strategy into its K–12 system. District superintendent Bob Stewart, a gray-haired man with more than a passing resemblance to Steve Martin, says GCCF is designed “to engage the entire community around this work.”

The germ of an idea for this center was planted in Stewart’s mind a decade ago, when he heard Kitzhaber, then in his second term as governor, talking about the importance of early, even pre-kindergarten, education. Stewart spent the better part of a decade turning it into a reality. “We’re making sure that all of our families have a voice,” he says. Linking education and healthcare services in one site gives low-income families, in particular, chances they would never have in regular school or healthcare environments. “The families are advocated for and feel some cheerleading behind them,” explains on-site clinic manager Jennifer Koons. “It motivates them more.”

Create enough healthcare/education/community center hubs like this across the state, and you’ve got a shot at realizing the 40/40/20 goals at the heart of Kitzhaber’s education reform. Add in better coordination between high schools and colleges, and you turn a possibility into a probability.

On the eastern side of the state, at the opposite end of the education spectrum, Mark Mulvihill is the superintendent of an education service district that is coordinating the development of college courses in rural high schools at a fraction of their usual cost. Called Eastern Promise, the program operates in four rural counties often left behind by education reform movements. It’s the sort of opportunity that Kitzhaber hopes all pre-kindergartners currently entering the system will have in fifteen years. Two local community colleges and Eastern Oregon University are bringing their classes into local high schools, “so senior year in high schools becomes basically the freshman year in college,” as Mulvihill explains it.

* * *

Oregon’s reforms are rapidly percolating into the mindset of educators, but they will still need more funding. After all, the state’s schools have been chronically underfunded for the past two decades. As in California, a tax revolt a generation ago, Ballot Measure 5, wrecked the ability of local governments to raise property taxes, loading $2 billion of unfunded education liabilities onto the shoulders of state government. At the same time, tough-on-crime measures have led to a 50 percent increase in the prison population over the past decade, with many predicting that the state will need to provide another 2,300 beds over the next ten years. Healthcare costs have similarly spiraled upward. As a result, per-student spending has plummeted as K–12 education has declined from 45 percent to 38 percent of the state’s general fund spending. Oregon’s school funding has been so low that in 2003 there was a derogatory Doonesbury cartoon on the phenomenon.

“We have,” explains Kitzhaber, “been relentlessly pulling money out of investments in early childhood, children, families and education, and spending it on healthcare and public safety.” The governor knows he can’t get more money for education until he reforms these other systems.

Kitzhaber has been talking about sentencing reform, although in the short term that’s likely to be a heavy lift. More immediately, he has pushed for ambitious healthcare delivery changes, beginning with the state’s Medicaid system, backed up by a federal waiver, along with nearly $2 billion in funding from Washington. He wants to use the savings to shore up a series of targeted, integrated investments in education, coordinated by Chief Education Officer Crew. This has meant moving more than 90 percent of the state’s Medicaid patients—about 600,000 people—into Coordinated Care Organizations, where primary care, wellness clinics, mental health centers, opticians and other services are either concentrated in one place or coordinated among the practitioners, allowing greater convenience for patients (dental care will be mandatory by July 2014).

One goal is that clinicians will catch problems before they escalate into expensive crises. CCOs are paid not by the number of tests they do or the number of hospital admissions they preside over, but by the number of patients they have and their health outcomes. “We want to insure more people,” argues Michael Bonetto, the governor’s health policy adviser. “But we have to do so in a way that doesn’t break the budget.”

The CCOs’ budgets grow at a fixed amount per year, now at 4.4 percent and set to go down to 3.4 percent next year—less than the expected 5.4 percent per capita increase among Medicaid patients nationally, and enough to generate huge savings over a ten-year period. While they do have to build up rainy-day funds, they are encouraged to work within their budgets. If they mismanage their funds, the state can yank its contract with them.

Since mid-2012, fifteen CCOs have been set up. Kitzhaber’s ambition is to adapt this model for the large insurance pools that provide coverage to teachers and other public employees, as well as for the state’s health insurance exchange, the Medicare system and, eventually, the private market.

It is designed, says Oregon Health Authority director Dr. Bruce Goldberg, to simplify healthcare delivery and to focus more on preventive measures. “The engine of our current system,” he says, “is more care, not better health.” Goldberg takes one 10-year-old asthma sufferer and Medicaid patient as an example, talking about how the boy had been repeatedly hospitalized for expensive interventions over a several-month period. Then a caseworker went to his house, identified various substances that were triggering the boy’s asthma and helped his family rid the house of them. Since then, he has not had to be hospitalized once. He’s healthier, and the Medicaid system is saving money.

“I’m excited by the changes we’ve seen with the emergency-room divergence project,” says Tammy Baney, Deschutes County commissioner and a coordinator of her region’s CCO. “I am ecstatic that someone who was seeking treatment nineteen times to as many as sixty-two times in a twelve-month period, that those individuals now have some sense of quality of life back.”

The governor talks of how a coordinated-care model would identify congestive heart failure patients at risk of catastrophic illness during heat waves and install air-conditioning units in their homes rather than wait, as the current system does, for them to get so sick they have to be admitted to a hospital ICU, at enormous cost. “The best hospital bed,” explains Goldberg, “should be an empty bed. That should be the goal of our healthcare system. Ultimately, our goal should be to keep people out of the hospital—fewer hospital beds and a healthier population.”

* * *

That’s the philosophy behind the network of Virginia Garcia clinics in the western Oregon counties of Washington and Yamhill. Since 1975, when the original clinic—named after a young, uninsured migrant farmworker who died from a foot infection—opened in a three-car garage, it has grown to a roster of 35,000 patients and more than 350 full-time staff. About half of the patients have insurance; the remainder pay out of pocket on a sliding scale based on their ability to pay. “Before I went to the Virginia Garcia clinic,” recalls patient Donna Lozon, “I had not enough money for prescriptions. Going to Virginia Garcia clinic, my diabetes is under control, my asthma is under control. We’re able to get on a computer and have contact with our doctors and whoever we need to make an appointment with.”

The Virginia Garcia clinics, in effect, were a CCO years before the concept had its turn in the spotlight. It brings low-income, marginalized and frequently undocumented people under a healthcare umbrella, delivering as many services as possible at one site, building up medical and mental health histories for those who might have never visited a doctor regularly. Through its outreach program, Virginia Garcia gives food to hungry patients and Christmas presents to impoverished kids. It even organizes healthy-cooking classes in its kitchens and hosts Zumba classes in an exercise area. “If we can be primary care homes, and everyone in the population knows where their primary care home is,” explains family practice doctor Laura Byerly, “and you have good information exchange, we’ll reduce duplications and have more information available when it’s needed.”

This year, the clinic is moving to what is known as an “alternative payment” method, allowing the clinic to bill the state for the number of patients it has rather than the number of visits it fields. Byerly hopes this will allow her to spend more time with each patient, talking through their health issues and setting up preventive care regimens. “At the end of the day,” says nurse Tran Miers, “the patient is in charge of his own health. Our role is to help the patient make self-management goals.”

Kitzhaber calls his reforms “trickle up” models: they start locally, with Medicaid and public employees’ health plans, and, he hopes, end up reshaping the national discourse. He likes to quote a doctor he spoke with recently about the healthcare reforms. “I’m terrified,” the doctor reportedly said, “because you’re asking us to build something that’s never been built before. But I’m really excited, because I get the chance and the opportunity to build something that’s never been built before.”

The governor’s team estimates that by 2015, the cost savings will run to hundreds of millions of dollars annually. From there on, the savings grow still larger as the CCOs fully hit their stride. Expanding this model nationally for Medicaid, Medicare and dual-covered patients would, Kitzhaber estimates, save the country $1.9 trillion over ten years, $1.5 trillion of which would represent federal savings. Even for Congress, he announces sardonically, that’s “real money.” It’s a way to start dealing with the deficit and national debt without decimating vital services, while also making Americans healthier.

This isn’t about big versus small government; it’s about clever government. It’s about using limited resources combined with new technologies effectively, and it’s about rewarding schools and health systems that generate good outcomes rather than those that simply throw resources at their problems without planning or coordination.

“We’re in the land of ‘Just do it,’” Rudy Crew says. “And I kinda think that’s exactly right here. We have to hustle to build the bridges to that future, and build the resources for that. You’re asking people not just to change the marquee in front of their building. You’re asking them to behave differently.”

In the May 13 issue, Sasha Abramsky wrote about one of the youngest and poorest senators, Martin Heinrich of New Mexico, who rose to the top as a supporter of labor and environmental issues.