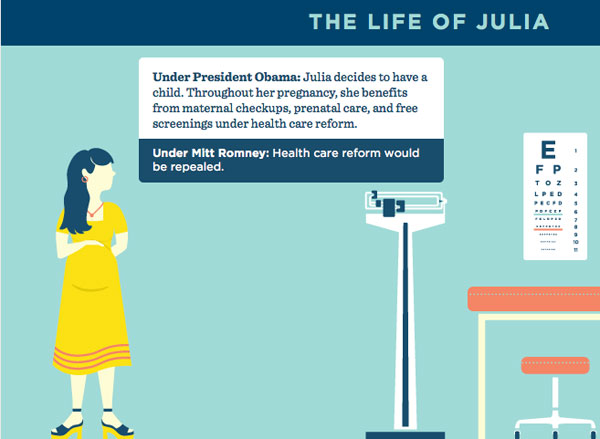

There’s been a lot of over–thinking it about poor Julia, the composite character created by the Obama campaign team. In my book, she’s a success despite the backlash, because, in keeping the focus all about policy, the infographic of her life got even her detractors to spell out the popular stuff that they’re against. Ross Douthat, usually a master of obfuscation, is forced to tick off the injustices:

The list of Obama-bestowed benefits includes Head Start when Julia’s a tyke, tax credits and Pell grants to carry her through college and low-interest loan repayment afterward, guaranteed birth control when she’s a 20-something and government-sponsored loans when she wants to start a business, all of it culminating in a stress-free retirement underwritten by Medicare and Social Security.

Oh, no! A stress-free retirement! Sounds awful.

Campbell Brown saw in “The Life of Julia” evidence of Obama’s ongoing tendency to condescend to women, calling it “a silly and embarrassing caricature based on the assumption that women look to government at every meaningful phase of their lives for help.” About a family member who lost her job, Brown writes, “Friends and family, not government, have been there at the dire moments when she has asked them to be.… [S]he, and they, wouldn’t have it any other way.”

Obama does condescend to women. But his policies generally don’t. Faux protestations that women are smarter than men: that’s condescending. Telling us it’s “common sense” that 15-year-olds can’t figure out how to take emergency contraception correctly: condescending. Backing policies that enable to women to access reasonably priced health insurance, earn fair wages, pay for college, start a small business: that’s showing respect.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

“The Life of Julia” doesn’t condescend to women, either. (And don’t forget, many of the policies Julia benefits from—the Small Business Administration loan, the better kindergarden for her son Zachary, Medicare—also benefit men.) We’re just unaccustomed to having our attention drawn to the way the government provides benefits and social insurance to a middle-class person throughout his or her life. Suzanne Mettler’s work has demonstrated that far more Americans make use of government programs—like the mortgage interest tax deduction, student loans, tax deductions for employer-sponsored health insurance and Social Security—than realize they do, a phenomenon she refers to as the “submerged state.” And even when people are aware of their reliance on government programs, they tend to be embarrassed about it, as the New York Times found, or dislike that they do. The backlash to “Julia” made it clear that, as Nancy Folbre put it, “liberals need to make a stronger case for collective investments in the development of human capital.” As Folbre points out, Julia is not the recipient of public assistance—in fact, she’s a “model member of the business community” who pays taxes, might have employees, invests in the economy through consumer spending:

Sure, we could move toward an every-man-for-himself economy. But private insurers typically have a financial incentive to exclude those most at risk. And choosing to invest only in your own human capital is a lot like choosing to invest all your resources in one small company.

Most of us will do better with a diversified portfolio that includes both socially responsible commitments and protection against long-term uncertainty.

What’s most remarkable about “The Life of Julia” is how much the government doesn’t help her out with, as my colleague Bryce Covert observed. Paid leave to care for Zachary? Childcare after she goes back to work? There’s no government help for Julia there, giving her plenty of time to rely on the bonds of kinship Brown so prizes.