The headline was “Beauty and the Beast.”

Yes, it was.

There are many reasons I haven’t written about the San Francisco magazine profile I did of California Senator Kamala Harris, back in 2003 when she was running for San Francisco district attorney, her first elected office, against incumbent progressive Terence Hallinan, whom the headline writers cast in the role of “Beast” because of his pugnacious style. I haven’t written about it, even though it was her first big magazine profile, and it’s not online; I have it all to myself.

Most of the reasons I’ve set it aside have to do with the way the story embarrasses me, not at all her, 16 years later.

It starts with that headline, which I didn’t write, but which still makes me shudder. It continues with my describing her, early on, as “black-eyed, raven-haired, latte-skinned.” I made much of her stylish clothes. Yikes. I apologize, to her and to all women everywhere. I also called her “smart and strategic, ribald and flirty,” and that’s probably not politically correct either, but I kind of stand by it.

The strangest but strongest regret I have is the freedom I felt to grill Harris about her relationship with then-Mayor Willie Brown, eight years after it happened. In my defense, it was, as her rival Joe Biden might say, a “big fucking deal.” So many people were talking about it back then, always to use it against her. And 25 years later, they still are. My 2003 article feels like a lost transcript of what actually happened, which is newsworthy and devastating to the misogynists who trash her for that relationship, while also a profile of her wiliness, her political caution, and her toughness.

Reading it, I feel strangely protective of Harris, given that she was 29 when she had that relationship—the same age as my daughter. My daughter is the other reason I haven’t written about Harris: She is her Iowa political director. Even though I believe that transparency cures almost all ills, I can’t do the kind of feature I’ve done on Senators Kirsten Gillibrand and Elizabeth Warren, given my daughter’s role. Though I would love to.

But when I went back and reread my story, as the right and left began to slime Harris with her relationship to Brown earlier this year, and to claim that’s why she won that 2003 district attorney race against progressive incumbent Terence Hallinan… well, after I stopped cringing about my own mistakes, I realized I had a historic document in my hands, for many reasons, during a historic presidential primary. Back then, I had a unique perch as a contributing editor at San Francisco. I was also at Salon at the time, and I was correctly perceived, then as now, as a writer on the left. I had voted for Hallinan, of course. But the magazine had ties to monied San Francisco—and Harris clearly had their support—and so both sides talked to me.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

I heard all of Hallinan’s grievances about Harris’s connections to San Francisco money and, yes, to Brown. I heard some stomach-turning sexist bullshit. I also heard a lot, from her admirers, about the way she prosecuted men who preyed on women and little girls, which was her distinguishing political advantage back then (along with, yes, big San Francisco money: Gettys and Buells and Swigs and Schwabs). At least, I thought her passion about prosecuting sexual predators was an advantage, although, honestly, many people didn’t seem to care much at the time.

But in this age of #MeToo and Jeffrey Epstein and, yes, the sexual predator she wants to replace, Donald Trump, suddenly our old conversations all felt relevant, too relevant to leave in my archive.

Of course, if I were doing a profile now, I’d ask Harris about some of her decisions as district attorney and later as attorney general. Her record as a prosecutor leaves her with many things to explain or defend. But I’m not doing that profile. I can’t. I wish I could. Still, I caught her at a formative time in her career, and in mine. So I’m telling you the story I told 16 years ago, and trying to tell it straight, without any spin. You can judge what it reveals. With all my disclaimers and disclosures, please consider this a memoir of a particular political time.

I first met Harris in a fancy San Francisco French restaurant where she loudly and graphically told me about getting a life sentence for a man who’d scalped his girlfriend with a Ginsu knife. People turned to stare. She went on, at the same elegant lunch, to describe getting a conviction for a Tenderloin murder victim who died with cocaine in her system and several other women no one cared about who she thought deserved justice. She had been part of the child sex crimes division at the Alameda County DA’s office and later formed a coalition to help child prostitutes when she worked for the San Francisco city attorney.

“The penal code doesn’t just apply to Snow White,” she told me.

This is what she wanted to talk about, not Brown. Or even her opponent Hallinan.

At that first meeting she insisted, “I don’t disagree with Terence’s platform,” which made sense, because she had worked for him. “I just think we need a different kind of leadership. The office is badly run.” When I repeated that to Hallinan, he laughed and said, “That’s not a good campaign—‘He doesn’t run a good office!’ I just don’t see her beating me.”

But she did.

I got to interview her mother, now deceased, Dr. Shyamala Gopalan Harris, whom I described as “an Indian-born endocrinologist and a bred in the bone feminist, who rejected labels about submissive Indian women” and who told me that “a culture that worships goddesses produces strong women.” The proud mother recounted some of the stories her daughter now tells on the trail, about taking Kamala and her little sister Maya (now the Harris 2020 campaign chair) to anti-war rallies in a stroller. “She was writing letters to Nixon to stop the bombing in Vietnam before she could really write her name.” And yes, Gopalan Harris told me the famous story about Kamala organizing kids to protest the policy at her apartment complex that didn’t let children play outside; she won.

Gopalan Harris also told me that when Kamala was young, she had to wear leg braces and orthopedic shoes—two hardships that undermined the image of effortless glamour the young attorney projected. Her parents divorced, and Gopalan Harris and her daughters wound up in the Berkeley flatlands, where, famously now, she was bused to tony Thousand Oaks Elementary in the wealthy white Berkeley hills. “I assume the divorce was very hard,” Gopalan Harris told me. “I’m sure Kamala suffered. We did not have an orderly television family life. I was always working.”

Something else her mother confirmed was the family’s shock at her daughter’s decision to become a district attorney. “People from our background become public defenders!” she declared. But Harris had spent a law school summer clerking at the Alameda County DA’s office, and she was hooked.

“I saw the discretion the district attorney has—who to prosecute, what to charge, how to run a courtroom,” Harris said, “and I realized it was important that people who care about social justice work on that side.” Now-retired Alameda County DA Tom Orloff told me she was “a very good deputy, she worked hard, she had good judgment.” As part of his sex crimes unit, “she tried several very difficult child molestation cases, and she won them all.”

While she was there, she began dating Brown, as he was ramping up his run for mayor. On election night in 1995, at a rally I covered, she famously handed him a baseball cap that read “Da Mayor.” City gossips wagged their tongues, but the chief city gossip, the late legendary Chronicle writer Herb Caen, blessed Harris in his universally read column, writing, “[Brown] has given up girls in favor of a woman, Kamala Harris, who is exactly the steadying influence he needs.” The problem was, Brown was already married, and despite his well-known womanizing over the years, he and his wife never divorced—and almost 25 years later, still have not.

He and Harris broke up not long after his election (though he appointed her to two state boards that together earned her roughly $80,000 a year). A close friend of hers told me Harris initiated the breakup, once it became clear that Brown would never leave his wife. “It was very hard for her, but Kamala wants a life partner,” she told me. And Brown confirmed the same (I have no memory of calling up Brown and asking him to talk about this; oh, the magic of time), saying, “She ended it because she concluded there was no permanency in our relationship, and she was absolutely right. I absolutely love her, and I wish like hell I could shed that absence of permanency, but I can’t. I think it’s in my genes.”

I don’t remember this, either, but apparently I asked Harris about her relationship with Brown, in a very judgy way, at our very first meeting. I remember she looked pained. Here’s what I wrote at the time:

At our first lunch, I embarrass both of us by asking at the outset: How could a smart feminist hook up with the womanizing mayor? Did she really think they had a future?

She pauses a long time before answering. “There aren’t a lot of us…lawyers, African Americans, people of color, interested in politics. There was a deep friendship there. He has a lot of wit and humor. I need my mind to be engaged—I’ve dated a lot of intelligent men.” She pauses and looks at my notebook. “Write that down!” But she ends the personal conversation there, except to confirm that she’s presently single and hopes that changes soon. “My husband has a very bad sense of direction—he hasn’t found me yet,” she quips.

(I’m happy to report that her husband, attorney Douglass Emhoff, finally found her in 2014. I did not confirm whether he indeed has a bad sense of direction.)

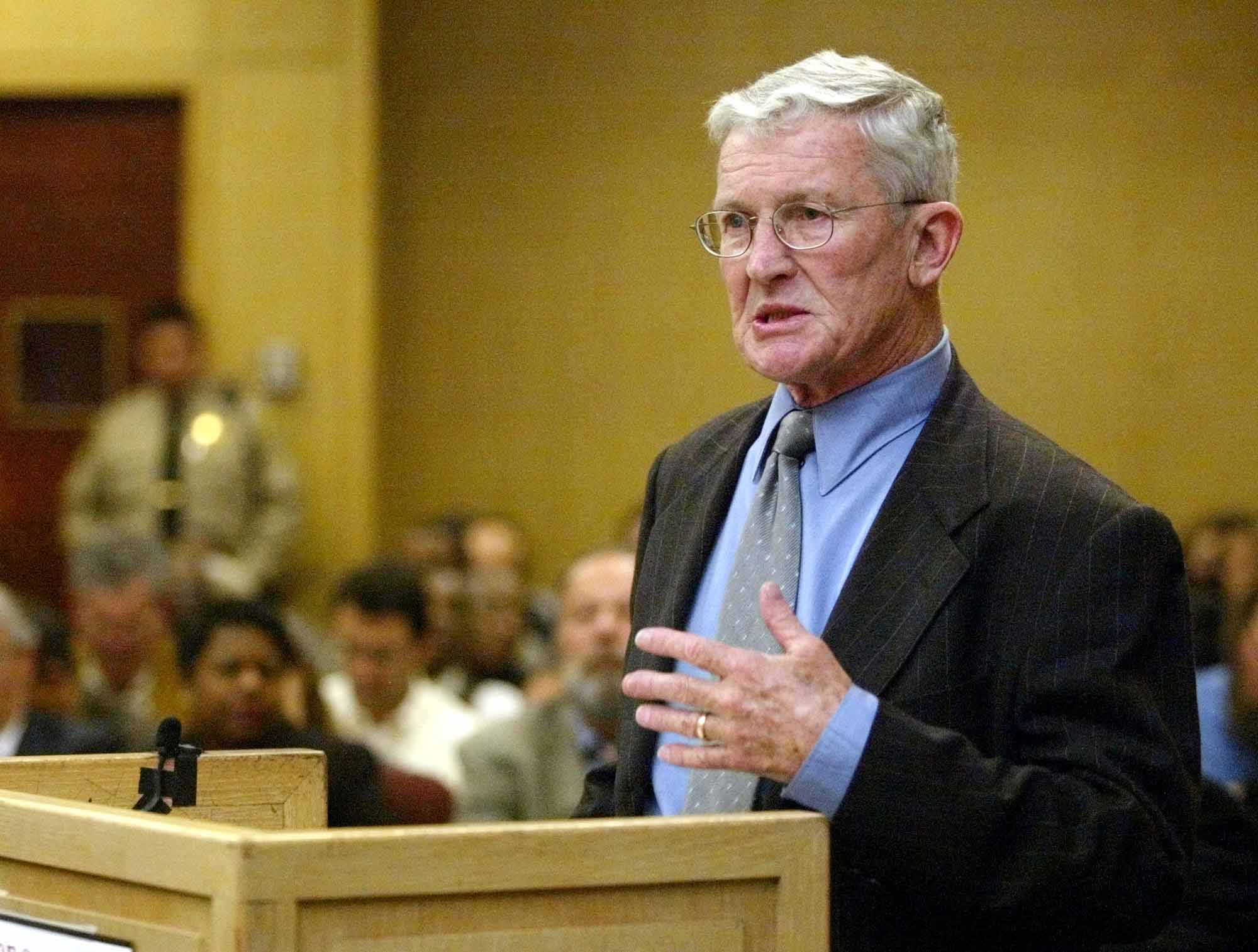

For a while during that first campaign, it seemed Harris couldn’t rise above her ties to Brown. She had gone to work as a deputy to Hallinan three years after she and Brown split. In 2003, five years after that, the incumbent DA insisted he hired her only “as a favor to the mayor.” When I reminded him that it was actually his top deputy, Dick Iglehart, who hired Harris, Hallinan insisted, “He asked her because the mayor asked him to.”

I reached Iglehart at the time, who denied the charge.

“The situation was, we were experiencing a brain drain, and Terence told me to interview some folks from Alameda County. I brought her over and he was deeply impressed. She was hired 100 percent because of her ability and competence.” For her part, Harris told me, “I liked a lot of what Terence was saying. He was hiring a lot of women and minorities and young lawyers, and I thought it could be exciting.” A conservative in the DA’s office told me, “She worked incredibly hard, and she was a great lawyer.”

After that, Harris ran into bureaucratic obstacles that are too boring 16 years later to talk about. Even progressives described Hallinan’s management style as chaotic. She led a revolt against the DA’s top deputy, who was widely disliked, and failed at it. Hallinan told me it was a case of Harris’s already stigmatized ambition: She wanted the guy’s job. She left for the city attorney’s office, working on issues of child prostitution and sex trafficking. And one of Hallinan’s backers told me, grudgingly, “She’s been running against Terence ever since.”

When I began working on the profile of her, I thought I’d wind up favoring Hallinan and be underwhelmed by this woman many dismissed as a socialite. But, honestly, the sexist way his supporters trashed her turned me against him and made me unexpectedly sympathetic to her, as did her evident competence and passion. Hallinan told me, “I kind of think I’m running against Willie Brown,” and one of his top investigators and best friends publicly suggested the DA’s slogan ought to be “an independent prosecutor who isn’t in bed with the police or the mayor.” (A third candidate, Bill Fazio, was a conservative tied to the cops.)

There’s always an unexpected issue in any political race that upends the contest. In this one, it was a trivial-sounding San Francisco Police Department scandal known as Fajitagate. After bar time, a group of drunk off-duty cops, including the son of the department’s second in command, beat up a couple of restaurant workers while trying to grab their fajitas; on-duty cops came and essentially tried to cover up their colleagues’ brutality. (This may sound like local trivia, but Jeffrey Toobin covered it extensively in The New Yorker.)

One complicating factor was that for the first time in history, the police department was led by a black man, Earl Sanders, a leader in the earliest efforts to integrate the Irish-dominated department. Sanders, appointed by Brown, was something of a local civil rights hero. By all accounts, Hallinan made a circus of the investigation, and in the end, the grand jury indicted seven cops—including, controversially, Sanders, on the grounds that he and top brass interfered with the probe. Black leaders howled at Sanders’s indictment, with some reason; high-profile agitator the Rev. Amos Brown termed it a “lynching.”

“This changes everything,” the longtime Chronicle political reporter Phil Matier told me at the Hall of Justice on the day of the indictments. “How [Harris] handles this could define her.”

She handled it with what has become her trademark caution. At the time I wrote something about her that I think was prescient: “Watching Harris during the indictment chaos, I found myself admiring her caution and poise but sometimes lamenting it too.”

Right away, she made a decision not to talk about the case; as district attorney, if she won, she might have to prosecute it. But from every side, she took flak—why wasn’t she standing up for the black police chief? Why wasn’t she backing Hallinan’s standing up to corrupt cops? She made one quiet gesture of sympathy for Sanders, attending his home church (pastored by Amos Brown) one Sunday after his indictment, but issued no statement. She couldn’t win, and she knew she couldn’t win, so she chose what now, to me, looks like the right course.

But I gave her a hard time anyway.

We had dinner after a local Black Leadership Forum where she publicly took the middle ground and refused to discuss the case—either to trash Hallinan and defend the black police chief or to defend Hallinan for going after police misconduct. I tried to push her off the fence, and I was kind of a jerk. Without taking a side on the case, she defended Sanders’s historic role in San Francisco’s black community. “People like me who’ve benefited from what he did owe him a lot.”

When I asked her why, if she was maintaining neutrality, she attended Sanders’s church the Sunday after the indictment, she got, as I wrote, “uncharacteristically defensive.”

“I didn’t make the decision based on politics. Maybe I should have. I’ve taken a lot of hits on it from donors and supporters. Somebody called me up and said: ‘Are you protecting the cops?’ It’s not like I stood up and made a big deal about his innocence. I went to his church. Yes, I knew he would be there.

“Would I call it a lynching? No. And I wouldn’t say race is the motivating factor. But you’ve got Ku Klux Klan racism, then you’ve got situations where people aren’t racist but what they’re doing is racist.”

I kept at it: Was this that kind of situation? Appropriately, she got irritated with me.

“Do I think the grand jury decided this is a black man, and we’re gonna indict him? No. But it’s unfair when people dismiss concerns about whether race played a role in a situation as ‘playing the race card.’ Race is potentially always an issue. But in San Francisco, we’re so progressive, we think we don’t have to talk about race.”

Even Van Jones—yes, CNN’s Van Jones, who then worked with a group called Bay Area Police Watch, thought Harris should have kept more distance from Sanders. “Anything she does to signal she’s closer to the police than Hallinan is will hurt her,” he warned.

But in the end, it didn’t. Hallinan eventually had to drop the charges against Sanders, and his handling of the situation helped doom him at the polls—with voters sympathetic to the police and older Sanders-admiring African Americans, as well as with younger police-reform-oriented black voters and liberals. Looking back, maintaining her silence while nonetheless visiting the police chief’s home church was a savvy and gracious gesture, the kind of political shrewdness that Harris, like her or not, has become known for. And for my attempt to overanalyze all of it at the time, I come off as a white concern troll.

A progressive lawyer who stayed neutral in the race, Peter Keane, told me she handled it perfectly, adding, “Look, the bottom line on Terence is he’s a good person but he’s impulsive, he’s political, and he doesn’t put professional issues paramount. He took a solid prosecutor’s office and ran it into the ground.” The conservative in the race, Fazio, told me the election was going to get even dirtier and suggested Harris wasn’t ready.

“That’s condescending,” she responded. “Bill doesn’t need to worry about me. I know I’m gonna be painted as this socialite, ‘the mayor’s ex-girlfriend,’ but that’s bullshit. I’ve worked my ass off for everything I have. I know this race is gonna get dirty, gritty, sexist, maybe even racist. And I have no fear. I’m working my ass off again, because I don’t intend to lose this election.”

And she didn’t. She didn’t lose her reelection for DA, either, or election and reelection as California attorney general or her first race for senator. None of this means she will be president or should be. None of this answers any of the valid questions people have about her record as a prosecutor.

But when I read this profile, after 16 years, I was struck by the ways Harris still seems the same person: savvy, strategic, cautious, fierce, “ribald and flirty,” backed by high-powered monied supporters but mostly committed to progressive values, still walking tightropes of race and gender.

Did I think she’d run for president back then? No. Five years before Barack Obama won the White House, I couldn’t see it, to be honest. But I can see it now. Again, I’m neutral in this race. She’s got almost two dozen rivals: five other women, including three other female senators; a black man and a Latino; a gay man, a democratic socialist, and oh, yes, Joe Biden. Harris may not get past them. But if she does, there’s reason to think she can handle a race against Trump, which will surely get “dirty, gritty, sexist, maybe even racist.” She’s been there before.