Governor Steve Beshear, Democrat of Kentucky, only has two weeks left in office, but he’s determined to go out with a bang. Beshear announced today that he is issuing an executive order restoring voting rights for nonviolent ex-felons who have completed their sentences. This will give 170,000 ex-offenders the opportunity to register to vote, according to the Brennan Center for Justice.

It’s a huge victory for voting rights in the Bluegrass State.

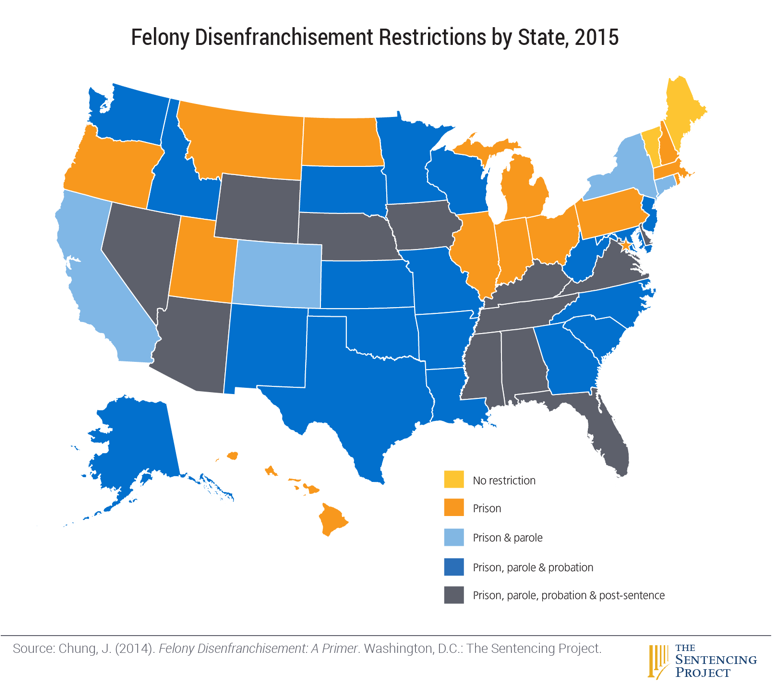

Kentucky is one of only three states, along with Florida and Iowa, where ex-felons cannot vote unless the governor personally restores their rights—preventing 7.4 percent of the voting-age population in the state and 22.3 percent of African-Americans from voting after serving their time.

Nationally, 5.85 million Americans can’t vote because of felon-disenfranchisement laws, according to the Sentencing Project, including 2.2 million African-Americans.

Thirty-nine states automatically restore the voting rights of all felons, while eight states automatically restore such rights to only some felons, notes Insider Louisville.

“The old system is unfair and counterproductive,” Beshear said at a news conference today. “We need to be smarter about our criminal-justice system. Research shows that ex-felons who vote are less likely to commit crimes and [more likely] to be productive members of society.”

Beshear’s Republican successor, Matt Bevin, has voiced support for restoring voting rights for ex-felons, as has Kentucky Senator and presidential candidate Rand Paul.

“I don’t think it’s fair or appropriate that we would take from somebody something that could be restored to them, that the nation would be better to have them in possession of all their rights,” Bevin said when he ran for Senate in 2013. Voting-rights advocates are hopeful that he will continue Beshear’s executive action.

Here’s how the program will work, according to Tomas Lopez of the Brennan Center:

For those who have not yet completed their sentences, people eligible will get a certificate of rights restoration and a voter registration application in the mail with their discharge papers. And people who have already completed their sentences will be able to contact the state to initiate that same process.

In 1792, Kentucky became the first state to adopt a constitution preventing those with criminal convictions from being able to vote. Many states adopted felon voting bans after the Civil War, when African-Americans were granted the right to vote with the passage of the 15th Amendment. “Felon voting restrictions were the first widespread set of legal disenfranchisement measures that would be imposed on African-Americans,” found a 2003 study from sociologists at the University of Minnesota and Northwestern.

Florida’s felon-disenfranchisement law played a major role in the 2000 election when the state attempted to purge ex-felons from the voting rolls, but instead ended up preventing many eligible voters from casting ballots. As I reported in my book Give Us the Ballot:

The NAACP sued Florida after the election for violating the Voting Rights Act (VRA). As a result of the settlement, the company that the Florida legislature entrusted with the purge—the Boca Raton–based Database Technologies (DBT)—ran the names on its 2000 purge list using stricter criteria. The exercise turned up 12,000 voters who shouldn’t have been labeled felons. That was 22 times Bush’s 537-vote margin of victory.

Jeb Bush approved only a fifth of ex-offenders in Florida who applied for voting-rights restoration while he was governor, according to Mother Jones.

At a time when the country is focused on the inequities in our criminal-justice system, ending the discriminatory system of felon disenfranchisement has to be part of any solution toward curbing mass incarceration.