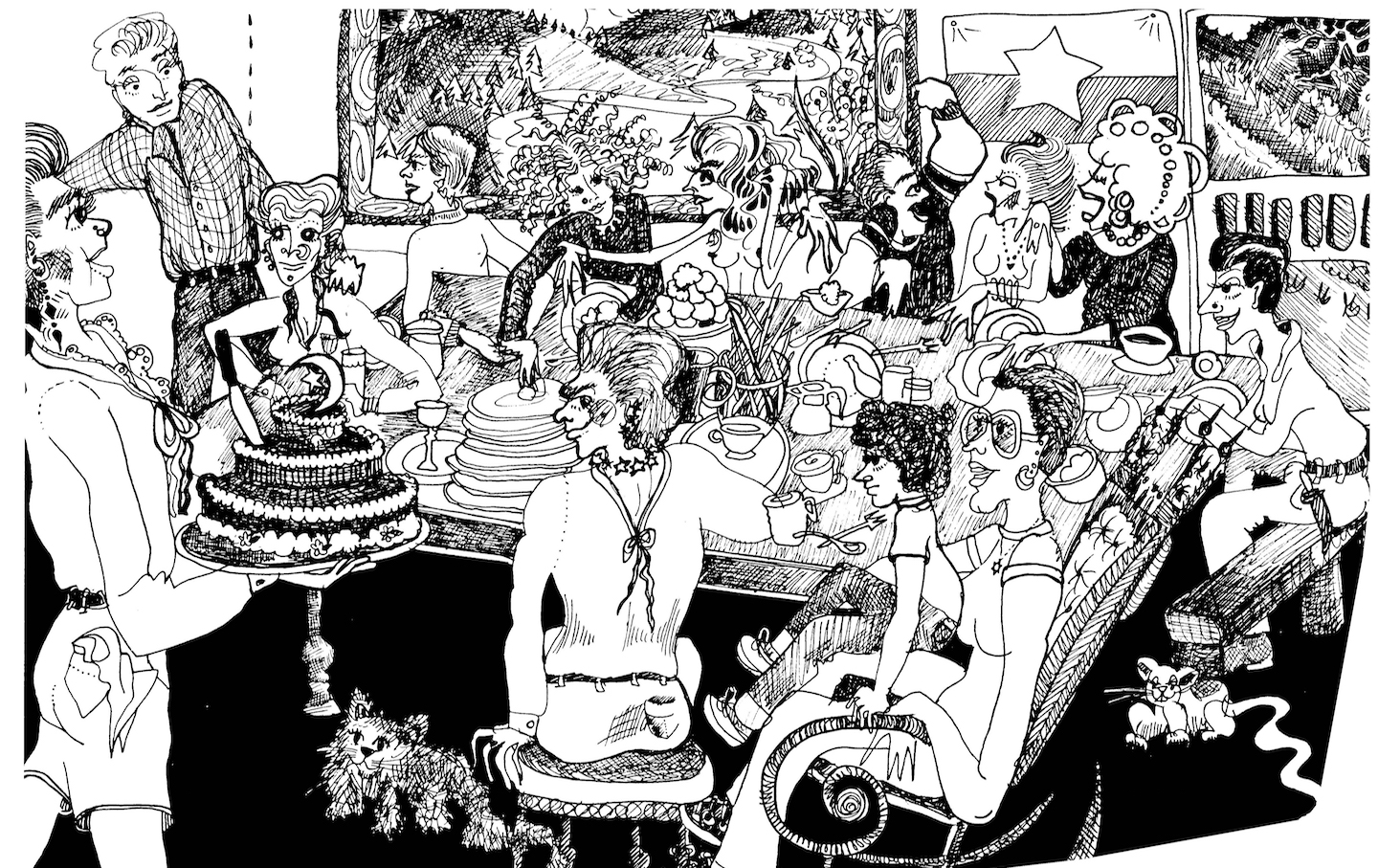

An illustration from Larry Mitchell and Ned Asta’s The Faggots & Their Friends Between Revolutions.(Illustration by Ned Asta / Courtesy of Nightboat Books)

The flood of Pride content began early this year, so I’d worn out the joke before we made it to June. “STONEWALL WAS A RIOT,” I’d type into my phone, playing the part of indignant radical each time a friend sent me a screenshot of some new petty offense: cynical rainbow branding, self-righteous gay engagement photos, bad-faith invocations of self-care—if you’re queer and online, you know the genres. Both sellout and radical were the joke’s object, and its punch line was a problem of political scale. Fifty years after the uprising often credited with sparking the modern gay liberation movement, what counts as keeping the anti-assimilationist candle lit on a darkening landscape of Trumpian reaction and piecemeal inclusion, and what’s just being a buzzkill about small wins?

Mainstream recognition can compromise our politics, and survival under capitalism requires constant compromise. It’s easy enough to nod along in agreement. But queer debates about what liberation looks like, what gets us there, and who is betraying us in the meantime can feel like a funhouse in which we’ve lingered too long, no more navigable for its tiresome familiarity. We wander among mirrors in search of an exit, decrying minor irritants as they briefly tower over us before passing out of view. Reading The Faggots and Their Friends Between Revolutions, written by Larry Mitchell, with illustrations by Ned Asta, feels like stumbling into a new room where many of the same actors and problems are reflected but with the fun restored. Its characters struggle to achieve a shared perspective on the title’s key terms, trying on and shedding pieties with ease. Refreshingly, the faggots and their friends relish these trials of collective self-definition. Mitchell and Asta remind us that we might still treat dissensus, as the faggots do, like play.

First published in 1977 by Mitchell’s own Calamus Press, The Faggots has circulated in PDF form in recent years, shared across the Internet as both queer consolation and fuel for fighting. Nightboat Books has now brought it back into print with introductory essays by filmmaker Tourmaline and performer Morgan Bassichis. Not quite speculative fiction, not quite allegory, and not quite polemic, The Faggots surveys a dystopian empire called Ramrod in its twilight years, where state agents struggle to enforce heteropatriarchal discipline as their kingdom crumbles around them. A mythic embodiment of masculine values, Ramrod runs on paranoia, violence, and avarice. Its claim to territory is frantic and insecure; when the book opens, the empire is young but already “disintegrating as the men lose more and more things they never owned in the first place.” As power expands and contracts, the titular cohort of dissenters alternates between insurgency and despair. “It’s been a long time since the last revolutions,” but rebellious energy percolates in private, sporadically bubbling into open antagonism. The faggots cruise one another, play dress-up, invent rituals, scavenge, scam, and stage occasional disruptions. In other words, they get by.

Like queers today, with our inexhaustible lexicon for self-description, Mitchell and Asta unfurl a charmingly arcane taxonomy of outsiders allied against “the men.” Most of the book is spent calling roll: We meet the “strong women,” who teach the faggots about fighting back and winning; the miserable “queer men,” who blend in among the powerful and pursue pleasure only in secret; the “fairies,” who “have left the men’s reality in order to destroy it by making a new one,” living together outside the city and worshipping their gardens; the “queens,” “named to commemorate the glorious past reign of the women,” who more openly and bravely flout the men’s imposed decorum; the “faggatinas” and the “dykalets,” street performers who “re-enact the sagas of the hideous, hidden violence of the men”; and of course, the “faggots” themselves, androgynous and sexually liberated but inconsistently politicized, still learning from their friends how to show up for one another.

These reclaimed slurs contribute to the book’s air of bold irreverence, but they also serve to more fully distinguish the faggots from their oppressors. “The faggots once called themselves the men who love men,” we’re told in Mitchell’s storybook narration, until they realized that in fact most men “were false and death-inflicting and obsessed with being strangers.” Encountering that cruelty is formative, in the book as in life, casting its long shadow over the faggots’ otherwise joyful communities. Individual faggots belatedly assume the foreground: Moonbeam, Loose Tomato, Lilac, Pinetree, Hollyhock, and Heavenly Blue band together to form the Tribe of the Rising Sons, making a home among other queers (the Gay as a Goose Tribe, the Boys in the Backroom, and so on) who live on Pansy Path.

Or at least I believe these to be the most essential of what might sound, misleadingly, like seeds of a plot. Small shoots of narrative sprout throughout The Faggots, but they don’t flower so much as mutate vertiginously. Mitchell seems too enthralled by his own imagination to reliably chart a world, much less a recognizable revolutionary program. Rather than chapters, The Faggots strings together aphorisms, sketches, and episodes that rarely extend beyond a single page. (This mode lends itself to activist excerption. Lines like “There is more to be learned from wearing a dress for a day, than there is from wearing a suit for a lifetime” surface occasionally in tweets or on signs at rallies.) Asta’s illustrations are as essential to the book’s effect as Mitchell’s text, adorning most pages with abstract embellishments or cartoon portraits of the busy cast.

Mitchell first conceived The Faggots as a children’s book during a stoned night out on Castro Street, the center of San Francisco’s burgeoning gay scene—aesthetic influences perceptible in the book’s steady, slightly reverent tone and patchouli-scented drawings. In 1973, Mitchell and Asta were among the founders of the multigender Lavender Hill commune in Ithaca, New York, where members experimented with dress, pronouns, and the collective distribution of resources and labor. (The short documentary Lavender Hill: A Love Story includes precious footage from the commune’s early years.) In a thoroughly researched introduction to the new edition, Bassichis argues The Faggots to be not simply a fanciful thought exercise but also a record of the utopian forms of life, love, and friendship elaborated at Lavender Hill.

Identities proliferate beneath Ramrod’s radar, as do proclivities, but the faggots and their friends share the status of nonmen. In Mitchell and Asta’s universe, solidarity is not a political imperative but rather a natural consequence of how domination cleaves society; the faggots become feminists, anti-capitalists, and anti-racists by virtue of those they find themselves among:

Those who have power—the men—decide which divisions they find expedient. They decide, for whatever reasons, who is not them and so who is to be hated. Those without cocks, those who are hungry involuntarily, those who refuse to work assiduously, those who want to play always, those who do not believe in male worship, those born with color, those who love their own kind, those who follow the wisdom of the great mother, these are the ones the men have decided to hate.

True to the ethos of Lavender Hill, opting out of the values of power is each dissident’s first revolutionary act and their gateway into community. The closeted queer men betray the faggots, but no one else does. Indeed, the book’s vision of frictionless collaboration along the margins is its most utopian proposal. If the men hoard everything at the expense of everyone else, everyone else quickly learns not to want what they’re denied. The faggots and their friends instead discover mutual aid, prefiguration, and the free exchange of pleasure: “The strong women told the faggots that the more you share, the less you need.” There’s nothing enviable about power, which is brutally secured but always tenuous and grim. “The men will do anything as long as they don’t enjoy it or talk about it,” goes one of many comparisons. “The trashiest faggots love who they do and talk of it often.”

Vital artists in their own right, Tourmaline and Bassichis are apt custodians of Mitchell and Asta’s idiosyncratic blend of forms and aims. (In 2017, Bassichis and a handful of collaborators performed a musical adaptation of The Faggots at the New Museum in New York.) In their contributions to the new edition, each stresses the cyclical rhythms of faggot existence. The founding iteration of Lavender Hill lasted only a few years before Mitchell and Asta returned to Manhattan, starting over in the East Village. The faggots, like their creators’ cohort, subsist in the city under the noses of the men until the countryside calls to them, where they cultivate their own rituals until the city draws them back. They flaunt or fight when they see an opening, and they bide their time in private when they don’t. They’re imperfect models, by which I mean they’re too much like us: Many hope that their pursuit of pleasure is enough to challenge power; they often hide from the men; they are rarely as bold as the women or the queens. “The faggots have never been asked to join the vanguard,” Mitchell readily concedes. “The faggots, it was noticed, want only to eat so they can play love play while the vanguard demands endless talk about the hunger of others and the seriousness of work.”

But with the help of the women, the faggots learn their history and take a longer view, certain that a revolution will come if they can keep one another alive long enough to see it. The book oscillates obsessively between hibernation and activity, deprivation and excess, abeyance and rebellion. In the absence of conventional plot, the faggots drift toward freedom. Their network grows as the men’s power weakens, ushering them haltingly from illicit survival to open community to more legible forms of political action. In quick succession, the final pages bring nonviolent vigils, organized rallies, legal defense teams, and a riot led by queens who are “tired of just surviving.”

Trapped in our contemporary funhouse—reading to distract myself from looping arguments about corporate pinkwashing and Stonewall’s legacy—I wanted an allegory of queers coming into power, and I was not exactly disappointed. Even so, the faggots’ mobilization is fitful and uncoordinated. Cause and effect cohere within each one-page sketch but not always beyond that. There were revolutions before, and another is imminent, but no one can herald it with assurance. In Ramrod, historical time mostly feels like a vestibule in which events might be freely reshuffled.

In this way, again, the faggots resemble us too closely. They search without direction for an exit called “revolution.” The book’s closing scene seems to promise one not by accelerating political action but by negating it. The faggots and their friends’ kaleidoscopic play can scramble the men’s categories and foil them in the short term, we’re told, but this confusion will soon become its own dead end. The next revolution will arrive only when the faggots absent themselves completely from the world defined by men—through fasting, celibacy, and the cessation of all activity and desire. It’s an 11th-hour bid for transcendence out of faggotry, motivated by the exhaustion of politics itself.

As the 1970s wore on and organized radical movements in the United States lost steam, many activists turned to newfound spiritual practices or rekindled faiths, desperate to fill the void left by a revolution that didn’t arrive. This widespread exchange of one millenarian vision for another may help contextualize The Faggots’ abrupt end, which casts the characters’ physical and psychic detox in vaguely New Age terms: “No movement and high invisible energy will be their goal.” But it brings me no closer to reconciling the book’s disparate revolutionary eruptions. This concluding amalgam of activity and exhaustion may be partly what Tourmaline and Bassichis have in mind when they assert the book’s timeliness in their introductory essays. “We are truly between revolutions,” writes Tourmaline. “Here we are, living in yet another period of both intensified repression and infectious rebellion,” Bassichis echoes.

The Faggots first arrived in a moment of contradictory signals, with high-water marks for feminism and gay liberation as well as a mounting conservative backlash. The score is hard to tabulate: 1977 saw Harvey Milk’s election to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, but also Anita Bryant’s antigay campaign in Florida; an unprecedented convening at the National Women’s Conference in Houston, but also at Phyllis Schlafly’s “pro-family” counterrally across town; the authorship of the visionary black feminist Combahee River Collective Statement, but also the ongoing decimation of black radical organizations by surveillance and state violence. The Faggots is brash and celebratory, but by Mitchell’s next novel, 1982’s The Terminal Bar, queer pleasure will have acquired an undercurrent of irony, even cynicism. Its protagonists are avowed “depressed fags waiting quietly for the end.” AIDS, of course, would soon change the texture of gay life irreversibly.

It’s true that our own time is at least as vexed. When I catch myself trying to force into coherence this book’s scattered proposals for another world, I entertain the possibility that I’m reading it wrong. As Bassichis notes, The Faggots scrupulously avoids dogma. It’s too weird and protean to serve as a guidebook for ongoing queer struggles or to propel us reliably into a revolution to come. Mitchell allows his text to be gleefully inconsistent, committing instead to experimentation, improvisation, and the pursuit of tactics over strategy. The Faggots warns against taking oneself or one’s identity too seriously, but it also insists on affording sex, style, and play the seriousness they deserve. “The faggots,” complain the vanguardists, “are too quick to believe that the revolution had come and so too quick to celebrate.” This might mean that the faggots can’t be trusted to recognize real opportunity on the horizon. Or it might mean that no one’s more ready.

Sam HuberSam Huber is a writer and senior editor at The Yale Review.