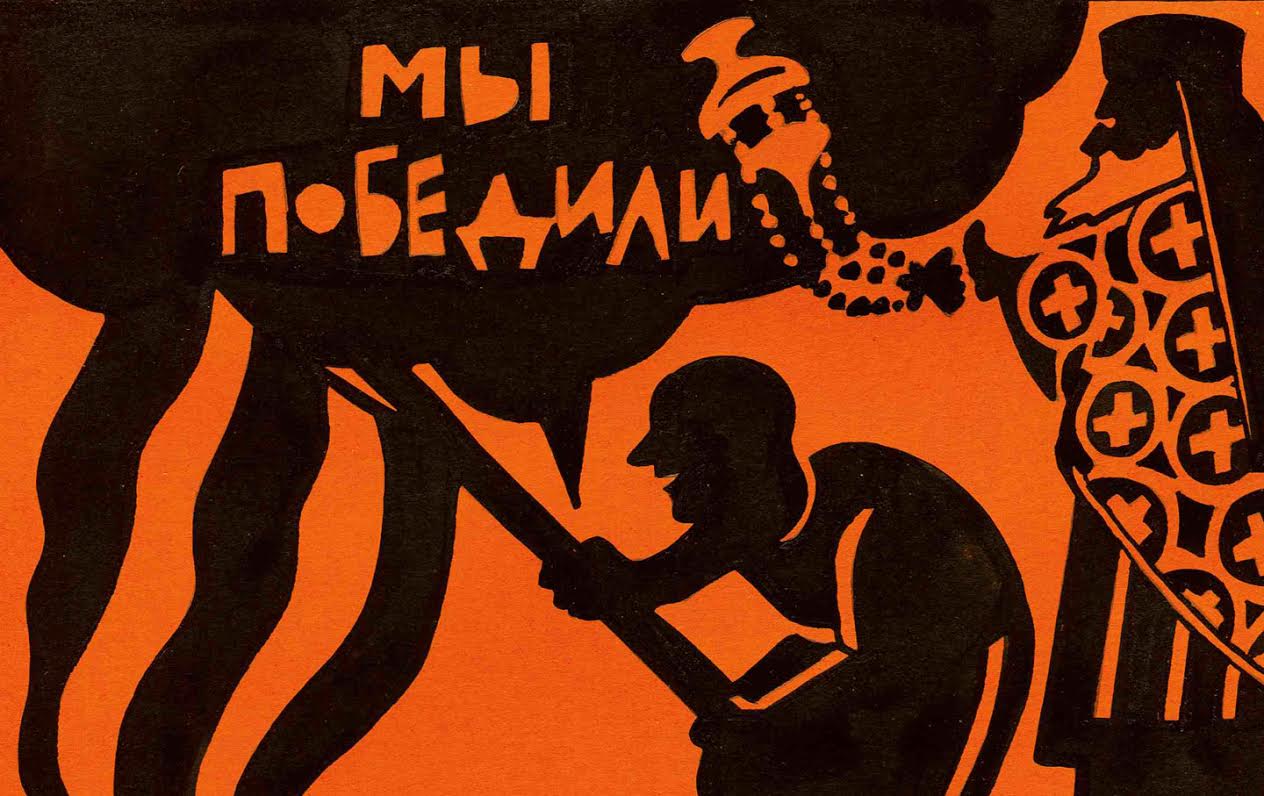

“We Won,” a 2015 meditation on Victory Day by Russian artist Victoria Lomasko.(Victoria Lomasko)

On May 9, the shell-shocked Eastern Ukrainian city of Donetsk celebrated. It was Victory Day, the annual commemoration of Germany’s surrender to the Soviet Union in 1945. Kiev, which is struggling to escape its Soviet past, no longer treats the day as a festive occasion; for the People’s Republic of Donetsk, or DNR, the holiday was yet another opportunity to side with Russia and the Soviet Union, and against Kiev. It had been a year since the DNR had declared its independence from Kiev, following the Maidan protests—which began with then-president Viktor Yanukovych’s decision not to sign an EU Association Agreement and ended with him fleeing the country after a series of armed clashes in the center of Kiev—and a year since Kiev’s prosecutor general had classified the DNR as a terrorist organization. Thousands of people have since been killed: fighters on both sides, and civilians caught in the middle. More than a million people have been displaced, in a horrible echo of the Second World War’s mass evacuations.

Prime Minister Aleksandr Zakharchenko, who was wounded in the battle of Debaltseve last winter, stood in the rain and made a speech. There were dark circles under his eyes, and he slurred his words; pro-Ukrainians later accused him of being drunk, but maybe he was just tired. Seventy years ago, Soviet heroes had defeated the fascists, he declared, and now their children and grandchildren were fighting fascists once again; the generation of victors had raised a generation of heroes. The past bled into the present, as the victories and losses of the Second World War mingled with those of the most recent war—or “antiterrorist operation,” as Kiev calls it.

Onlookers stood under umbrellas, cheering “Thank you!” and throwing flowers at the stony-faced new heroes of Donbass, the region that became Eastern Ukraine after the Russian Revolution. Men with fighting names like Givi and Motorola held their white-gloved hands in fixed salutes as they rode by on tanks painted with orange-and-black St. George ribbons, a mark of Russian patriotism. In the evening, there were fireworks, as is customary on Victory Day, though one might have expected the residents of Donetsk to be tired of explosions after nearly a year of intermittent shelling.

It didn’t rain on Moscow’s Victory Day parade. The Kremlin spent millions of dollars to make sure of it: A few days before the holiday, a spokesman at Russia’s Federal Air Transport Agency announced that a group of planes would be ready to “attack” any rain clouds with cement particles and silver iodide. When Vladimir Putin made his speech on Red Square, he was surrounded by veterans and foreign dignitaries from China, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Zimbabwe, Cuba, and Egypt, as well as Winston Churchill’s grandson, a Tory MP. Most European leaders skipped the parade to protest Russia’s actions in Ukraine. For many Russians, it looked as though the once-Allied nations had forgotten that it was the Soviet Union that rescued them from Nazism, at the cost of tens of millions of Soviet lives. Putin thanked the Allied countries graciously for their help winning the Great Patriotic War, as it is known in Russia, but had harsh words for those who were violating the postwar principles of international cooperation. Intercontinental ballistic-missile carriers rolled through the streets, and fighter jets formed a huge “70” in the sky.

Seventy Years of Victory! posters all over Russia cried, as if Victory were not a historical event but a permanent state of exaltation. The St. George ribbon snaked across walls, windows, cars, trains, lounge chairs, bread loaves, dog collars, vodka bottles, flip-flops, fingernails, and even sex toys. On nearly every Moscow street corner, a Russian flag waved beside the red Soviet Banner of Victory, the one raised over the Reichstag in 1945. Kiosks around the city sold T-shirts showing Putin dressed as a Soviet soldier.

“When Brezhnev’s generation died—the generation of leaders who actually fought in the war—the legitimacy of the Soviet government disappeared with it,” Boris Kagarlitsky, director of the Institute of Globalization and Social Movements, told me in an interview at his Moscow office. “Now Putin’s government is trying to establish legitimacy not based on any real historical experience, but by using late-Soviet style and aesthetics. On television, you see dancing girls in uniforms of the Second World War—half of the girls with the red Soviet flag, and half with the tricolor Russian flag. The message is very clear: Russia is the successor of the Soviet Union, the heir to Victory. It looks like a mockery, a way of hiding the fact that the war was won by a different government, a different political and social system. They’re claiming a historical inheritance to which they don’t have sufficient rights.”

Just before Victory Day, Radio Svoboda reported that Anatoly Ptitsyn, a 90-year-old veteran in Kaliningrad, hoped his Victory Day wouldn’t be spoiled by rain, as his roof was full of holes. He didn’t have the money to fix it, and the local administration refused to help. “Our country only needs dead heroes,” he told a journalist.

The media used stories like Ptitsyn’s to illustrate government hypocrisy, but such reports also point to the dismantling of what remains of the Soviet-era social safety net. Universal education, medical care, housing, and pensions for the disabled and the elderly were some of the most cherished achievements of the Soviet Union, even if the systems had many problems, including low salaries and a lack of up-to-date training and technology. But today, with less money to spare on populist gestures, Putin is continuing the process of privatization that began with Yeltsin. Even as the Russian government insists on its symbolic association with the Soviet past, it is moving toward a neoliberal social model antithetical to Communist ideals. The real value of pensions is falling; increasing numbers of Russians are living below the poverty line; and there have been strikes by healthcare providers, teachers, factory workers, and construction workers, often because of unpaid wages. For many, Russia’s orgy of patriotism looks like a tactic to divert attention from the country’s economic troubles.

* * *

November 7, 1941, marked the anniversary of the October Revolution. Just days after German planes had bombed the Kremlin, Stalin ordered a parade that would be watched around the world. It was an extraordinarily risky way to raise morale and cow the enemy.

In his speech, Stalin invoked the great minds of Russian art and science and Russia’s military heroes, from Aleksandr Nevsky to the generals who defeated Napoleon. The symbolic union of the USSR with imperialist-Orthodox Russia was uncongenial to some revolutionaries, but it was a reliable crowd-pleaser. Much as Putin is working to harness the symbolic power of Soviet Victory, Stalin harnessed the energy of all the victories of the Russian Empire. It didn’t matter that the revolution had promised to abolish the imperial system for good. The old victories, heroes, and gods were too potent to be discarded.

This year, as part of its attempt to align itself with Europe rather than Russia, Ukraine declared May 8 “Victory in Europe Day” and replaced the Soviet term “Great Patriotic War” with “Second World War.” May 9 became “Victory Day Over Nazism in World War II,” a solemn rather than a festive affair. Kiev’s traditional Victory march was replaced by a peace march, without fireworks. The Motherland statue, a war memorial in the shape of a giant woman with a sword, was crowned with a garland of red poppies, which are used in Europe to commemorate the war dead. St. George ribbons were frowned upon, or worse. A video circulated online showed two Ukrainian nationalists berating an older man trying to leave his home wearing a ribbon; when he refused to go back inside, they doused him in kefir.

Shortly after Victory Day, Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko signed new laws that attached criminal penalties to the display of Soviet and Nazi symbols in almost any context, and to denial of the “criminal character of the communist totalitarian regime of 1917–1991 in Ukraine.” A second law recognized the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) as “independence fighters” and made it a criminal offense to deny the legitimacy of their actions. Soviet people were taught to despise UPA and OUN as collaborators and murderers, and not without reason: During the Second World War, the groups made alliances with the Nazis and massacred tens of thousands of Poles and Jews as part of their plan to cleanse Ukraine of foreign occupiers. They also killed a number of Soviet (as well as Polish) political figures, notably Nikolai Vatutin, one of the Soviet Union’s most important generals.

The new “memory laws” are an act of symbolic violence against the civilization in which many Ukrainians, Russians, and other Soviet people grew up, and for which millions lost their lives fighting the Germans. Poles, Jews, leftists, historians, and advocates of free speech and human rights are among those who have criticized the legislation. Many have pointed to the irony of the fact that the so-called “decommunization” laws use Soviet-style tactics: the suppression of political speech and debate, and the official imposition of a redacted version of history.

* * *

Last year, on May 2, pro-Russian protesters attacked an Odessa demonstration in support of a united Ukraine. After several hours of street fighting and a chase, the pro-Russian activists took refuge inside the Odessa Trade Unions building. When the building caught fire, most likely from a Molotov cocktail, 42 people inside were killed. The police did not intervene, firefighters arrived only after a long delay, and after more than a year, Ukraine’s official investigation has yielded few results. The “Odessa massacre,” as it is usually called in Russia, provoked fear and fury among Russians and pro-Russian Ukrainians, becoming a central justification, in the Russian media and popular imagination, for Russian intervention in Ukraine. It has been used as proof of Maidan’s murderous intent, and of the necessity of Russia’s “rescue” of the people of Crimea and support for the Eastern Ukrainian separatists. (Though the Kremlin adamantly denies sending soldiers and military equipment to Eastern Ukraine, there is increasing evidence to the contrary.)

The conflict between Russia and Ukraine has the bitter intimacy of a family feud. The two countries are bound together by geography, trade, culture, history, and language. Russians have long cast themselves in the role of “older brother” to Ukraine: It’s a blood relationship, if not an equal one. In the hierarchy of Soviet nationalities, Ukrainians were second only to Russians; if the Soviet Union was a communal apartment, as one Communist Party official described it in 1924, Ukraine got the second-biggest room.

World War II tested the friendship between the two nations. Western Ukraine was incorporated into the USSR in 1939–40, and many of its inhabitants had no desire to join the Soviet family. The Germans exploited this enmity, striking deals with Ukrainian nationalists. At the same time, a large proportion of Red Army soldiers, officers, and generals were Ukrainian, and many of the war’s decisive battles were fought on Ukrainian territory. Stalin described the Red Army as the defender of “peace and friendship between the peoples of every land.” Ukrainian people and Ukrainian land were at the heart of this friendship, and at the heart of Victory.

After the war, the Ukrainian Republic played a correspondingly central role in the emerging Victory cult. War commemoration was incorporated into coming-of-age rites, wedding processions, and national holidays. This helped counteract the wartime surge of Ukrainian nationalist sentiment, some of which the Party had encouraged for reasons of morale. Remembering wartime triumphs also served to dull the memory of the violent collectivization of farms and the resulting famine of 1932–33, which killed millions of Ukrainians. According to Party rhetoric, Victory was the final proof that it had been necessary to unite the Soviet republics, whatever the cost. The Soviet family had been the only possible road to the (relative) autonomy of its members; it was the Soviet project that had granted the freedom to be Ukrainian, and that unified Ukrainian territory for the first time in history.

Stalin died in 1953, but the friendship of the peoples lived on. In 1954, the Soviet Union celebrated the 300th anniversary of the Pereiaslav Treaty between Russia and the Cossack Hetman Bogdan Khmelnitsky, which resulted in the incorporation of most of what is now Ukraine (not including its western regions) into Russia. Much as Russians this spring could purchase nearly anything in St. George orange and black, in 1954 Ukrainians could buy a wide variety of items sold in wrappers decorated with images of the Kremlin and of Kiev’s statue of Khmelnitsky astride a rearing horse, and the words “300 Years”: underwear and cigarettes, wine glasses, a specially brewed beer. Russia and Ukraine held parades and concerts and exchanged symbolic gifts. The most valuable of these was Crimea, a province that had never been part of Ukraine.

* * *

Belgorod is a midsize city 25 miles from the northeastern Ukrainian border, just 50 miles from the Ukrainian city of Kharkov. Because of its location, Belgorod was especially hard hit during the Second World War. It was occupied by the Germans from October 1941 until early 1943, and was recaptured by the Germans in 1943, at the culmination of the Third Battle of Kharkov. The Red Army liberated it in the summer of 1943, after the Battle of Kursk, the world’s largest tank battle, which saw 863,000 Soviet and nearly 200,000 German casualties. British-Russian journalist Alexander Werth wrote that when he arrived in the area north of the city, the earth was dead for miles around and “the air was filled with the stench of half-buried corpses.”

Belgorod has always had close ties to Ukraine. In 1918, it was part of the short-lived Ukrainian State established by German-backed Hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky. When Skoropadsky was overthrown, Belgorod became the seat of a provisional government. Some residents speak with guttural accents, like those common in Eastern Ukraine, and drop the occasional Ukrainian word into their speech.

Until recently, people moved freely and frequently between Belgorod and Kharkov. Olga and Sanya, a married couple I met in Crimea five years ago, used to visit friends in Kharkov on a whim, for an overnight visit or a birthday party. Now a border crossing requires time, documents, and money, and many who crossed in the last year were refugees escaping the violence in Eastern Ukraine. Olga and Sanya told me sadly that many of their Ukrainian friends no longer speak to Russians on principle, and that one friend from Kiev disowned her sister for returning to Crimea after it became Russian. Families have been divided by the conflict, or destroyed; Sanya told me that at Easter there were long lines at the border, because so many people went to visit the graves of relatives who’d been killed in the fighting in Eastern Ukraine. Now Ukraine is planning to erect barbed-wire fences, watchtowers, and tank traps along its entire border with Russia, in an effort to keep out Russian fighters, weapons, and supplies.

Olga and I woke early on the morning of Victory Day to go to Belgorod’s Immortal Regiment march. Organized several years ago by journalists from the respected independent station Tomsk TV-2, the Immortal Regiment began as a nonpolitical, nongovernmental initiative to encourage people to collect and share information about family members who had served in the war. On Victory Day, participants march carrying pictures of their relatives. It’s an attempt to focus attention on the real people who fought in the real war, on historical truth rather than jingoistic fantasy. Not all of the stories on the Immortal Regiment’s website are about heroic feats: One person wrote, for example, about how his grandfather arrived late to the draft office and was never seen again.

In Belgorod, where the streets had been empty the day before, we were astonished by the number of people marching. Olga kept seeing acquaintances carrying portraits of their grandparents or great-grandparents. Many of the portraits we saw were handmade, often with carefully assembled collages of photographs and words.

“I have goose bumps,” Olga said.

A group walked by carrying a huge red Victory Banner and a large portrait of Stalin. Nearby, a man in a mass-produced red Stalin T-shirt was waving a Soviet flag and carrying a bunch of red roses. Another man in an identical shirt soon joined him. A heavily made-up young woman paired the same top with red high heels. One of the slogans of Victory Day was “We are proud and we remember,” but some people seemed to have forgotten quite a lot.

Balloon vendors sold tanks and helicopters alongside SpongeBob SquarePants dolls and hearts that said I Love You This Much in English. Men dressed as Cossacks stood on guard, whips in hand. Whole families wore Soviet uniforms or camouflage; one woman pushed her uniformed toddler in a stroller, looking like a parody of a war nurse. Family members of all ages competed to see who could assemble and disassemble a rifle fastest, and posed for photos with an actor-soldier on a vintage military motorcycle. Antique tanks swarmed with little children, and a boy in uniform marched in circles on the back of a military truck.

After the parade, we went to grill sausages and chicken with some of Olga’s friends. Dima, an old acquaintance, told me that his grandfather had made it all the way to Berlin, where he fell in love with a German woman, married her, and brought her back to Russia with him. Then they were repressed, sent first to the taiga and then to Kazakhstan. They were lucky they weren’t shot.

Dima had been working in construction, building houses on the Russian-Ukrainian border. Now no one wanted houses there, and Dima was broke.

“Death to traitors,” he said ironically, lifting his glass of vodka, “and to fascists.”

We went up to the roof to watch the fireworks, which were just across the street. The explosions were deafening, and the air was thick with smoke.

When we went back downstairs, I asked Lyosha, another old acquaintance, what he thought about the conflict in Ukraine.

He leaned in close to me, speaking softly, and told me he’d been feeling paranoid. He was so bombarded with propaganda that he’d started to see conspiracies everywhere he looked.

“When I heard about the fire in Odessa,” he said, “I wanted to drop everything and go and fight for Donbass. But now I think about how I reacted, and I wonder if the whole thing was just a Russian provocation. I get a weak signal from a Ukrainian TV station. Sometimes I watch it and then watch the Russian news, just to compare. They’re all lying. They tell you everything is black and white, but it’s not that way at all. There are no heroes in this. In Belgorod, we all know people who’ve come from Eastern Ukraine. They tell us about being attacked by Ukrainian forces and by the rebels—by both sides. They saw it with their own eyes. They were as close to the fighting as we were to the fireworks.”

He held his palm up to his face to demonstrate.

“Do you think Russian soldiers are fighting in Donbass?” I asked.

He lowered his voice to a whisper. “I think so. But everyone thinks I’m wrong—even my friends. Even my mother.”

We drank to peace, again and again.

Sophie PinkhamSophie Pinkham recently received a PhD in Slavic languages and literature from Columbia. She is the author of Black Square: Adventures in Post-Soviet Ukraine.