The author of "Why I Make Terrible Decisions" discovers the dark side of Internet fame.

Michelle Goldberg

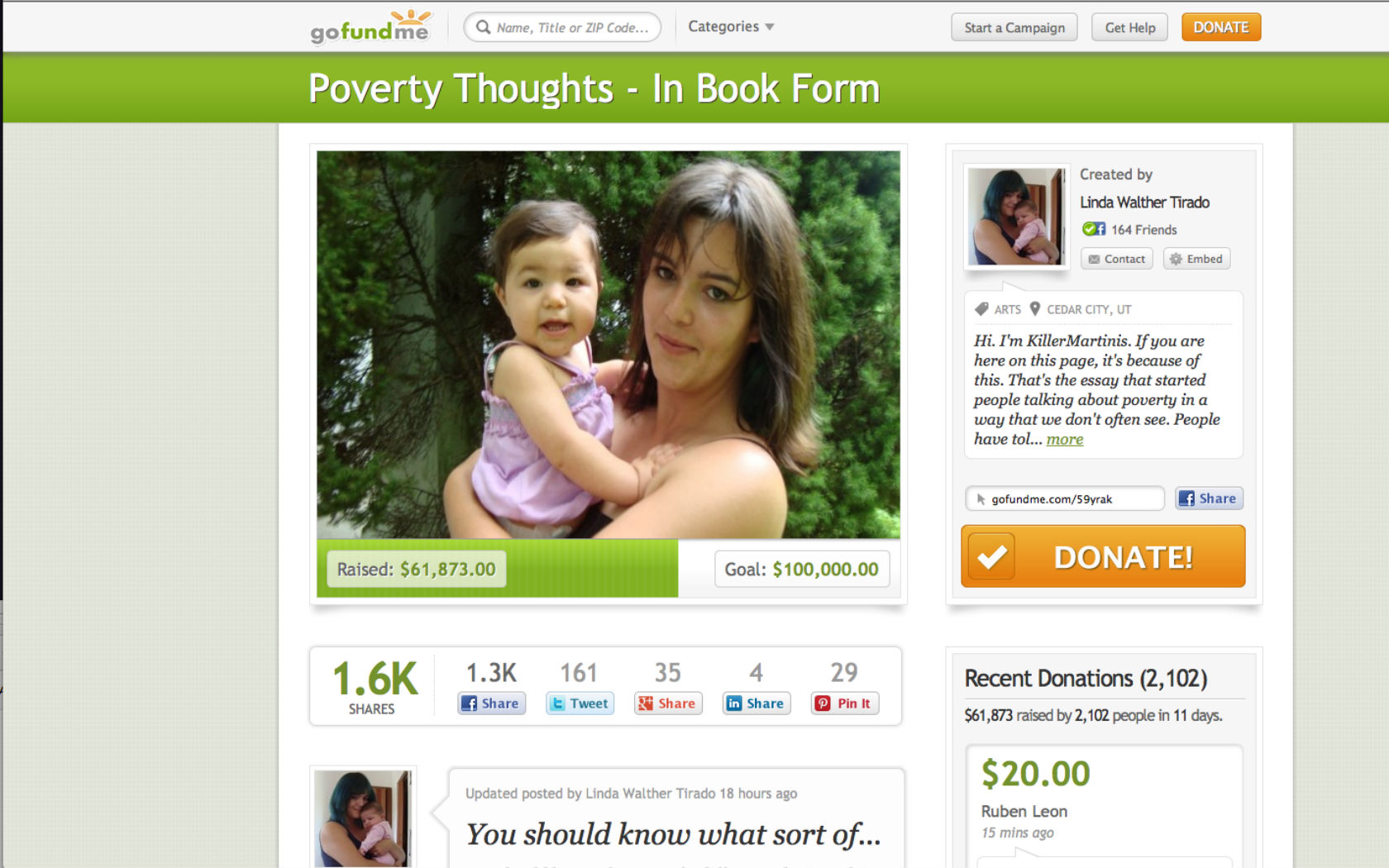

Linda Tirado (Courtesy of gofundme)

First, Internet fame brought Linda Tirado a miraculous windfall. Then it put her reputation through a meat grinder. She’s been saved and she’s been savaged. She has emotional whiplash.

Last month, Tirado’s essay about poverty, “Why I Make Terrible Decisions, or, poverty thoughts”—originally written as a comment on a Gawker thread—went viral, and she was able to raise over $60,000 on GoFundMe to turn it into a book. On the cusp of a publishing deal, she’s been able to quit her job as a night cook at a cheap chain restaurant.

At the same time, though, there’s been a tidal backlash against her, replete with online death threats and media denunciations. If the initial narrative about her was that she was, as The Huffington Post dubbed her, the “woman who accidentally explained poverty to the nation,” the new story is that she’s nothing but a middle-class fabulist preying on naïve and guilty liberals. Much of this story is false, but it has legs. Earlier this month, Tirado was included in a CNN piece headlined, “2013: The Web’s year of the hoax.” This week, the backlash reached The New York Times, which included her in an article headlined, “If a Story Is Viral, Truth May Be Taking a Beating.”

Given that the Times piece was about fact-checking, it’s ironic that it got its facts wrong. Listing viral stories that later turned out to be “fake or embellished,” reporters Ravi Somaiya and Leslie Kaufman described Tirado’s piece as “an essay on poverty that prompted $60,000 in donations until it was revealed by its author to be impressionistic rather than strictly factual.” This is, at best, highly misleading. Somaiya and Kaufman’s passive construction—“was revealed”—elides the fact that the person doing the revealing was Tirado herself. She filled in her backstory in a post on her fundraising page dated November 14—well before most of her donations came in. It was almost a week later that The Huffington Post published her original essay, which gave her visibility a huge boost.

In other words, she was not hiding anything from most of the people who contributed to her book project. And what we know about the nuances of her story—particularly her middle-class upbringing—we know because she put it out there.

As Tirado explained in her November 14 post, as well as when she spoke to me ten days later, she’d had many privileges as well as many bad breaks. Her grandparents, who raised her, sent her to private school during part of her childhood—though not, as some have reported, to the fancy Cranbrook boarding school that Mitt Romney attended. The confusion about this is partly Tirado’s fault. In her essay, she wrote of receiving a partial scholarship to Cranbrook but being unable to afford the rest, but said her family “knew damn well what Cranbrook was and they were determined that I would have a chance at it.” Her point was that they had ambition and social capital, which is why they tried for the scholarship in the first place. Critics interpreted it as an admission that she is a Cranbrook alumna.

From there, the idea that she was a rich boarding school kid who has never known hard times took on a life of its own. A piece in a Houston alternative weekly, posing as an investigation, claimed that Tirado “has never experienced true poverty,” apparently because she hasn’t always been poor. “Her LinkedIn profile states she’s been a freelance writer and political consultant since 2010, and has worked in politics since 2004, a claim backed by 27 decent political connections,” wrote reporter Angelica Leicht, noting that Tirado had met President Obama while interning for a politician “who obviously wasn’t disgusted by those rotten teeth.” CNN, in turn, cited Leicht’s piece as revealing that “Tirado…has worked as a political consultant, attended a private boarding school and is married to a US Marine.”

As it happens, Tirado has been upfront about the fact that she dropped out of college to bounce around the country working on political campaigns. (When I first wrote about her, I spoke to one of her former bosses, who confirmed to me that her teeth held her back.) She’s written about marrying an Iraq veteran, and only fell into severe poverty during her first pregnancy. Ohio’s Hamilton County Court has records of an eviction case against her from this time, and she sent me documentation of her enrollment in Medicaid [PDF] and the Women, Infants and Children supplemental nutrition program for poor pregnant women, new mothers and their kids [PDF].

This was the period Tirado was writing about in her essay. It ended when her grandparents, from whom she’d become estranged, came to her and her husband’s rescue when they were living in a squalid motel, moving them to Utah and setting them up in a trailer. They went on food stamps—she sent me a screenshot of their computerized records—got restaurant jobs, climbed into the working class, and eventually bought a foreclosed house with her grandparents’ help. This is the story that Tirado has been telling ever since she became famous, and none of her detractors have found anything to contradict it.

To be clear, it would be easy, reading the essay that initially catapulted Tirado into the limelight, to get the impression that her current situation was more dire than it actually was. “Cooking attracts roaches,” she wrote. “Nobody realizes that. I’ve spent a lot of hours impaling roach bodies and leaving them out on toothpick pikes to discourage others from entering. It doesn’t work, but is amusing.” You would have thought that she was still spearing roaches, instead of describing something she’d done a few years ago. Those who gave her money before she clarified things might be entitled to feel misled. But she’s tried, since becoming famous, to be as straightforward as possible. The idea that she’s been running a scam that others have uncovered is absurd.

Underlying that idea is a set of assumptions about what a real poor person looks like. Leicht, for example, dwells on Tirado’s “past as a person from a much different background” as if it proves that she’s never known desperation. “The idea that class mobility only goes one way is incredibly harmful to American society,” Tirado said when I spoke to her on Tuesday. She’s right. Further, it’s bizarre to slam someone whose essay was called “Why I Make Terrible Decisions” as a person who isn’t really poor because she’s had opportunities that she squandered. Tirado never tried to depict herself as a perfectly deserving victim. Her essay was meant to push back against the idea that only those who’ve never made mistakes deserve help. “Nobody gets to where I am without a mix of bad luck and bad calls,” she says.

It is not easy to see oneself vilified in the media, to be the subject of a great outpouring of sneering Internet rage. Tirado has written about suffering from depression; even if she was perfectly stable, having her entire digital existence combed through by hostile strangers searching for inconsistencies would not be easy.

Still, even with all the anger directed at her, Tirado’s life is undeniably much better than it was before she wrote her fateful piece. There is her new writing career—she is, she says, in the initial stages of a book deal—and, thrillingly, the chance the to spread some of her bizarre good fortune around. A widow and mother of six in Washington State wrote to her after reading her story; like Tirado, she had dental problems and was inspired to set up her own crowd-funding page, though it didn’t seem to be going anywhere. “I know that I may never have work because of my teeth…and I am not pretty. Poor, almost toothless, and older,” she wrote. In response, Tirado offered to pay her dental bills. “This is not charity,” Tirado wrote. “This is one struggling mom to another, because I have it to pass on.”

Documents: Women, Infants and Children supplemental nutrition program enrollment, 7/2/2010 Central Clinic financial agreement, 10/21/2010 Medicaid enrollment, 7/27/2010

Michelle GoldbergTwitterMichelle Goldberg was formerly a senior contributing writer at The Nation.