A monthly gathering of personal enthusiasms and observations about the passing scene, “Field Notes” will, in the tradition of The Nation, draw attention to things overlooked or often misunderstood.

Oklahoma City

My visit began and ended at the Oklahoma City National Memorial, a work of public art that surprised me by being quite unlike Ron Arad’s World Trade Center Memorial or Maya Lin’s Vietnam Memorial in its mission to go beyond the framing of a traumatic event—the 1995 bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building—to promote a community’s continuing goals and aspirations. Whether the memorial’s admirable communal spirit would extend to the rest of what I came here to see is another question.

Although the memorial was a natural first stop, I’d come to the city for a different reason: I wanted to talk with local educators and with staff members of Generation Citizen’s Oklahoma City chapter about their program to, as they put it, “empower young people to become engaged and active citizens.” Generation Citizen, a youth civic-education nonprofit, is nonpartisan and has a presence in middle and high schools across the country—but I reckoned the path to legislative action for students eager for change was a lot steeper in Oklahoma City than in places like New York City or Lowell, Massachusetts. And yet, the recent and widely publicized 10-day teacher walkout to protest education-funding cuts suggested that red-state Oklahoma might hold a surprise or two for this parochial New Yorker.

The memorial was the first of these surprises, and it is importantly related to the rest. Its 168 empty bronze, wood, and cast-glass chairs—each bearing the name of someone who died in the 1995 bombing—are well-known, as are the long, narrow reflecting pool and the two gates that enclose the park, one bearing the timestamp 9:01, a moment before the event, and the other 9:03, the moment after.

But there is more to it: The composition is spatially generous and open in a way that expresses something besides grief. As you walk along, your eye moves away from the chairs and across the reflecting pool to a berm with a grove of fruit trees surrounding the one tree, an elm, that survived the bombing. The berm’s wall displays an inscription honoring everyone whose response to the event helped to reinforce the spirit of the city and the nation. Here—and in the adjacent museum—is where this memorial begins to celebrate the resilience that Oklahomans insist is their birthright: a readiness to help others, or in the words of the annual Oklahoma Standard Award, “Service, Honor, and Kindness.”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

The memorial is the work of Torrey and Hans Butzer, two Americans living in Germany who permanently relocated to Oklahoma City after designing it. By being unusually open to the community from the very inception of the project, the city and the designers charted a smooth course between architectural conception and public emotion, averting the contentious debates that beset Arad’s and Lin’s memorials. The result is a populist commemoration, deliberately more representational than abstract in conveying its message that Oklahomans are always ready to confront trauma.

Let’s hope so. There are cataclysmic events that make the heart fierce like the 1995 bombing of the Murrah building, and then there is a long-term trauma like the one on the city’s Southside, where segregation, unemployment, and lack of economic mobility do not seem to have summoned the helping hand Oklahomans profess to extend in times of crisis. It’s in this neighborhood, at U.S. Grant High School, that Generation Citizen is providing a curriculum in action civics. The student body at Grant is 80 percent Hispanic and close to 100 percent below the poverty line. Principal Greg Frederick describes the day after Donald Trump’s election as devastating for his students, many of whom were crying: Would their families be deported, should they drop out, were they safe inside the school? According to Drew Rhodes, who teaches history, government, and the Generation Citizen curriculum, Frederick delivered a dramatic address over the intercom assuring students that they had rights, that ICE would not and could not breach the doors of Grant, that they’d have to roll over him first. He saved a lot of kids that day, Rhodes tells me.

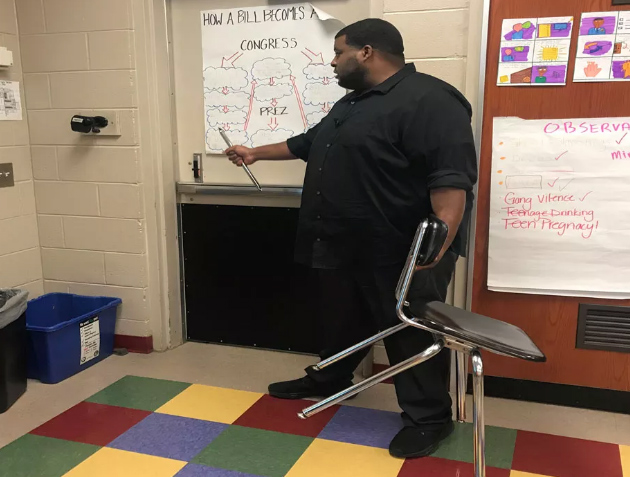

Months later, when Frederick attended a meeting of high-school principals, he watched a presentation from Generation Citizen describing their civics curriculum and the democracy coaches from local universities who would help teachers implement it in their classrooms and turn learning into action. “That sounded like our school,” he says. However challenged his students are economically, however endangered they may be, he and Rhodes stress that they are politically aware because they have to be. Grant students had already staged a walkout in 2016 to protest education-funding cuts; learning how government works and taking a course that would allow them to engage in effective legislative action seemed a natural next step. As he listened to the presentation, Frederick knew he had teachers, Rhodes among them, who were ready for what Generation Citizen had to offer.

In addition to giving each classroom a democracy coach to help with the civics curriculum, the organization supplies students with a manual that refines their understanding of the way government works and urges them to uncover the root causes of why things are the way they are. After that, it is up to each classroom to decide what issue they feel most passionate about.

Rhodes showed me the boards from two of his classes where the students posted the results of their neighborhood surveys and arrived at the issue that seems most urgent. One board identifies the lack of free access to higher education for qualified undocumented students, lists the root causes of the problem (racism figures prominently here), posts personal statements from students about the importance of such access, describes their legislative outreach (who they called, who responded, who did not), and the legislative action proposed. In this case, the students at Grant were able to reach Cyndi Munson, Democratic member of the Oklahoma House of Representatives, who will sponsor a bill to, in their words, open “Oklahoma’s promise to undocumented students…strengthening Oklahoma’s economy through a boost of our skilled workforce.”

The other board calls for a bill that would allow all undocumented immigrants who take a driver’s-education course and pass the state’s test to obtain a driver’s license. This may seem a taller order, but the students’ research and testimonials about its urgency were persuasive, detailed, and moving enough to prompt Mickey Dollens, another Democratic member of the Oklahoma House of Representatives (who has visited Rhodes’s classroom twice), to sponsor a bill.

These are impressive results, to say the very least.

Although Generation Citizen takes a nonpartisan approach to action civics, it does look as if it is responsible for returning this small part of Oklahoma to its once-progressive roots. When I mention this to Amy Curran, GC’s Oklahoma site manager, and Elizabeth Sidler, GC’s Oklahoma senior program associate, they tell me that, while they do want to shift the culture in Oklahoma’s classrooms, the organization’s goal of inclusive, democratically run schools is not a partisan issue. Maybe not, but in a deep-red state, there must be students who want to endorse charter schools, advocate for a large police presence on campus, or support a border wall—goals antithetical to the values of Generation Citizen. That can happen, CG CEO and co-founder Scott Warren tells me but, he adds, the amount of research the students are required to do in the GC program often ends up modifying such views by opening a debate to many more voices.

Healthy debate around controversial issues is not a part of Oklahoma’s political culture, yet U.S. Grant High School has hosted several of them. It’s not as if Drew Rhodes’s students don’t know what they are up against in advocating for a better education and a fairer shot at the American Dream. They do know. Rhodes, who is African American and has a keen and devastating analysis of our society coupled with a ferociously unsentimental optimism, is ready when I ask him what happens if either of the students’ bills fail in the legislature. What then?

“If it doesn’t pass, then we are talking about obstacles and how to overcome them,” he says. “One thing about kids in the inner city is that they know about obstacles. Some of them have to overcome a dozen obstacles before they even get to class. They have to figure out transportation; they have to figure out where they are going to get their breakfast or if they are going to get their breakfast; they’ve had to figure out where they’re going to sleep the night before; they have to figure out where their mom is or where their dad is and who’s going to take care of their brothers and sisters, what bill needs to be paid and who might be out there looking for them to do them some harm. All that before first hour. So legislation not passing will be just one of those obstacles they need to face. We can’t be complacent in the face of these obstacles.”

The annual Oklahoma Standard Award given out at the memorial is a symbol of citizens’ resilience in the face of obstacles, their willingness to step up, their “spirit of limitless generosity.” This year it went to Drew Rhodes for an act of bravery. His school was on lockdown one day last semester. There was a shooter in the hall. The latch on his classroom door was broken. He stood against the door, barring entry with a chair and a part of a broken desk. A student filmed it all and it went viral, inspiring an online debate about teacher pay, school safety, and funding.

“My students are the brave ones,” Rhodes said upon accepting the award, and he is right. They step up everyday. Generation Citizen has stepped up, and so has Rhodes. Will Oklahoma do the same?