It is not uncommon for leaders to be defined by crises. In New York City, however, mayors have a habit of being resurrected by them. Rudy Giuliani was widely loathed in his hometown before his display of stoicism on September 11, 2001, made him a national figure. His time in office dwindling, Michael Bloomberg used the 2008 financial crisis to force a rewriting of local law so that he could capture a third term and rank among the most consequential chiefs in the city’s history.

This article was produced in partnership with City Limits, an urban affairs news site covering New York City.

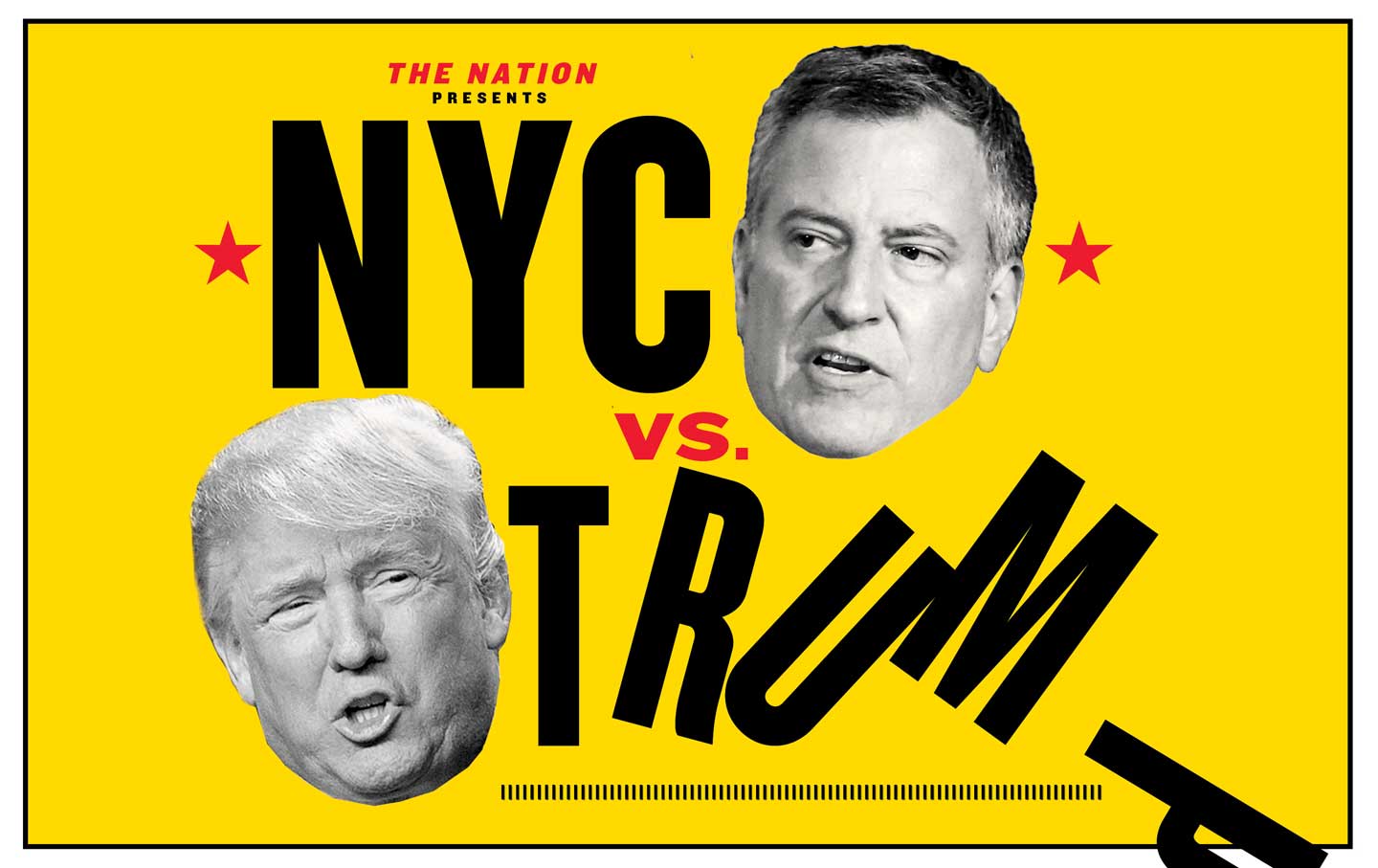

Now Bill de Blasio—besieged by investigations, at war with the press, hobbled by rival politicians, scarred by management mistakes that have overshadowed his significant accomplishments—seems to have been rescued by the least likely of lifeguards: the terrifying reality of a Donald Trump presidency.

The mayor, to some extent, saw it coming. When he sat down with The Nation five days before the 2016 election, de Blasio certainly expected and hoped for a Clinton victory. But he detected a turning point—and an opportunity—in the contours of the national campaign. “This will sound heretical, but almost regardless of the result of the presidential election, I do believe this is the beginning of a new progressive era,” he told us. “My sense is that I cannot recognize this dynamic in anything I’ve experienced in the preceding 36 years, going back to the election of Ronald Reagan…. There’s so much consistent and effective progressive activity, and it’s happening in so many places—including a lot of counterintuitive places. We’re kind of staring something in the face that has not been fully accounted for.”

The November 8 results indicate that he was more right than he knew. Since Election Day, de Blasio has taken on a role as a leader of the official resistance to the coming Trump regime. The mayor has pledged to use his power to create a safe space in the city for some of the progressive ideals that the next president has vowed to countermand. He met face to face with the president-elect to argue his point of view, e-mailed supporters to rail against Trump’s plans, and delivered a major speech—in the historic setting of Cooper Union—in which he pledged to defend the city’s values of tolerance and inclusion.

De Blasio’s efforts have been noticed. NYC Mayor Teaches Democrats How to Fight Trump, proclaimed a headline on Daily Kos, while Politico announced: Bill de Blasio Finds His Mojo as the Anti-Trump. Indeed, the fight against Trumpism has animated the first few weeks of de Blasio’s 2017 reelection campaign.

This is more than mere posturing. The beliefs are genuine and the stakes incredibly high—especially in a city where hundreds of thousands of immigrants are threatened by the policies that the president-elect has promised to adopt. At the very least, de Blasio is creating a node of resistance to Trumpism, a bunker in which progressives can hunker down against the new administration—and against those Democrats who will accommodate it. In these days of little hope, de Blasio has offered at least a ray of it.

But the real work lies ahead. During our interview, when a Hillary Clinton presidency was all that any of us could see, de Blasio sized up the progressive potential exposed by the 2016 race. “Now the challenging part is, outside of the crystallizing dynamic of a presidential campaign, how do you sustain and build on that?” he asked.

That remains the question. Can Bill de Blasio overcome the constraints of his office, the weight of his political mistakes, and the limits of his own progressive vision to create a dependable bulwark against the new president? And will he even survive as mayor long enough to confront the challenges of the next four years?

✰ ✰ ✰

Back in the summer, when The Nation first proposed a sit-down with the mayor, he was awash in woes. There were the multiple investigations by the US Attorney for the Southern District of New York, Preet Bharara, and others into fund-raising by the mayor and his associates that might have violated the law, as well as alleged favors that he might have granted to the well-connected. The GOP-controlled State Senate had attempted to humiliate de Blasio by giving him only a one-year extension on mayoral control of the schools instead of the standard seven. The number of homeless people crowding the city’s shelters continued to rise, and two of the mayor’s rivals—Governor Andrew Cuomo and City Comptroller Scott Stringer—were making hay off that crisis, needling him whenever possible. A few of de Blasio’s top staffers had recently headed for the exits. A group called NYC Deserves Better, led by the man who ran Bloomberg’s $102 million reelection campaign in 2009, had issued a casting call for Democrats willing to mount a primary challenge. And the newspapers seemed fascinated by de Blasio’s habit of ditching Manhattan to work out—sometimes until mid-morning on weekdays—at his old gym in Brooklyn.

All that controversy obscures a basic truth: New York City is a better place than it was the day de Blasio took office. Crime is down, police encounters are fewer, private-sector job growth has been remarkably robust, and de Blasio has engineered new wage and sick-leave protections for many workers. More people signed up for the city’s municipal ID card—which provides undocumented immigrants with government-issued identification and other residents a way to get museum discounts—than live in the entire city of Boston. A universal pre-kindergarten program has been up and running, with remarkably few hitches, since de Blasio’s first year. Income-targeted housing is now a requirement whenever a developer takes advantage of a rezoning. Mental-health policy has finally received mayoral attention. The list goes on. “I think he can legitimately claim a progressive record in virtually every issue he’s had an impact on,” says David Birdsell, the dean of Baruch College’s School of Public and International Affairs.

But the mayor’s numbers don’t reflect a runaway success. His 47–47 split in a November Quinnipiac survey suggests that de Blasio faces a tougher reelection campaign than the city has seen in some time. Sitting in the Peach Room in his official Gracie Mansion residence on November 3, de Blasio leaned his 6-foot-5 frame forward in his chair to close the distance with a significantly shorter reporter and sized up the gap between his performance and his poll numbers. “I think good news doesn’t travel as fast as bad news,” he offered. “I think you see many people in executive office who experience this kind of phenomenon. You are never surprised when a leader has accomplished a lot, but other issues are more prevalent in the media.”

De Blasio is confident that the weight of his accomplishments—lower crime, universal pre-K, more jobs, more housing—will register when it counts. “The positive, from my point of view, is: Those things all did happen, are all happening, and are deepening in some cases. And we’re going into the year when we actually are going to have the conversation.” The mayor harked back to his 2013 campaign: “I did not have the support of the business community—I actually had the active opposition of a lot of the business community. I didn’t have the support of the Democratic Party establishment…. I had no editorial boards—except The Nation, thank you very much. And I had a couple of substantial unions, but the rest of labor was against me.

“That hand to play would have normally been sure defeat,” he continued. “Why, instead, did we end up winning the primary outright, without a runoff, and going on to the highest vote percentage for anyone for an open seat for mayor since 1898? I would argue it’s because the vision and the ideas were what people cared about and the changes [what they] wanted to see. We have gone and done them.”

Indeed, de Blasio came into office bearing an agenda progressives liked. He was also handed a lot of baggage they resented, like the notion that a left-wing politician couldn’t manage the complex machine that is New York City’s government. Fair or not, that was the book on John Lindsay and David Dinkins, and the New York Post and others began writing its third chapter even before de Blasio was sworn in—predicting rising crime, fleeing businesses, busted budgets, and other nightmares.

The mayor’s team knew going in that any misstep would be seized on to ratify the narrative that de Blasio was an inept manager or a political hack. And so, the mayor told us, he has tried “not to be long on ideals and short on accomplishments, or obsessed with moral niceties and not knowing how to do the mechanics of government.” The smooth implementation of universal pre-K and the municipal ID, de Blasio’s settling of a long list of labor contracts left lingering by his predecessor, the continuing fall in crime—these are all part of a string of successes that belie the narrative of de Blasio as a feckless leader.

But the homeless crisis and various slipups—like setting and then blowing a deadline for finally wrapping up repairs to the extensive damage caused by Superstorm Sandy—hurt his case. And de Blasio’s testy relationship with the press, uneven approach to transparency, and nonchalance about appearances have drowned out his more substantive successes.

De Blasio does have his critics on the left, who disagree with him on policy and priorities. But many of the progressives I spoke to were pleased with his record, albeit concerned about his PR. “The things he’s done as mayor are what he promised to do,” said Joel Berg, one of the city’s most prominent antipoverty advocates. “Like most progressives, I’m a little frustrated by the challenge of communicating this message and telling people that it’s working.” Another veteran progressive advocate put it this way: “The fundamentals of the city are so much better than even people who thought he would succeed could have expected. But the missteps have been bigger than expected. He’s been hurt by flubbing the politics.”

✰ ✰ ✰

During his first year in office, de Blasio’s ambitions shifted to a bigger stage as he tried to convene a national progressive movement with an urban base. De Blasio says that the effort grew out of a meeting at the White House shortly after he was elected, when he realized that mayors in many cities were articulating the same economic-justice issues upon which he’d based his campaign. He was named chair of a Cities of Opportunity Task Force at the US Conference of Mayors in 2014. Then, in the spring of 2015, he delayed his endorsement of Hillary Clinton, hoping to push her left, and announced a 14-point Progressive Agenda to Combat Income Inequality.

After virtually every other Democratic politician in the state robotically endorsed Clinton, de Blasio’s move was depicted as an act of extreme hubris. As the months passed, his holdout became increasingly awkward. The mayor ended up endorsing the former secretary of state in October 2015—too late to curry favor with her, too early to matter when the Sanders surge came. The progressive agenda didn’t seem to be making much progress either: An Iowa forum that de Blasio tried to organize around economic-security issues was abandoned when none of the candidates agreed to come.

According to the hacked campaign e-mails released by WikiLeaks, Clinton’s team mocked de Blasio behind his back. To his face, they rebuffed his bid to do official surrogate work in Iowa—he went anyway, partly on his own dime, to knock on doors—and gave him a minor role at the convention. On election night, de Blasio tried to get in the game by making stops around the city to encourage turnout, an earnest but insignificant gesture. A few hours after he made his final stop at the corner of Fordham Road and the Grand Concourse in the Bronx, the world, of course, changed.

The next morning, with Trump’s victory official, de Blasio strode to the podium in the Blue Room at City Hall. “New York is the symbol of America to so much of the world,” he said. “We are a showcase, but we are also a target because our values work. We embrace our role as America’s greatest city. Today is a time of reflection. Tomorrow, resolutely and purposefully, the work begins again.”

While de Blasio’s earlier bid for a national role was mocked as an ego trip without a map, much of what happened in 2016 has confirmed his political sense, if not his tactical skill. The Democratic base was clearly open to a far more progressive platform than the one Clinton planned to adopt, and while she did ultimately move left, the issues that de Blasio stressed are precisely the ones she should have emphasized. Since November 8, the mayor has avoided saying “I told you so,” but his postmortem on the election suggests that’s what he’s thinking.

“One thing that had to happen was a much more central focus on the economy and a progressive, populist economic message, which clearly was in the platform,” he told NY1 News the Monday after Trump’s election. These were “powerful ideas—you know, raising taxes on the wealthy, increasing wages and benefits, things like paid family leave, paid sick leave, things that really would have resonated with so many people hurting in this country…. It isn’t the first time that Democrats have failed to put forward a strong, powerful, progressive economic message.”

A week after the election, the mayor met with Trump for more than an hour, alone, and said afterward that he’d laid out his opposition to mass deportation, the widespread implementation of stop-and-frisk, moves to loosen the regulations on Wall Street, and the appointment of Breitbart News’s Stephen Bannon as chief strategist. A few days later, de Blasio chose the backdrop of Cooper Union—where Abraham Lincoln and Barack Obama both made major addresses—to deliver a speech in which he promised that the city “will fight anything we see as undermining our values.… We will use all the tools at our disposal to stand up for our people.” De Blasio pledged to take legal action against any Muslim registry, to defend immigrants against deportations, to refuse participation in any federal stop-and-frisk scheme, and to “ensure women receive the health care they need” if Planned Parenthood is defunded. “This is New York,” the mayor said. “Nothing about who we are changed on Election Day. We are always New York.”

It’s not immediately clear how far beyond New York’s borders de Blasio will be able to carry his message, however. Right after the election, his aides envisioned a quiet role on the national stage. Moreover, the likelihood of a presidential run by Cuomo, who for three years hasn’t missed a chance to thwart and belittle de Blasio regardless of its effects on the city’s residents, will complicate any aspirations the mayor has of leading a progressive push. The good news is that he is not the only big-city mayor ready to oppose Trump. If urban America—substantially foreign-born and richly diverse, the piston in the US economic engine—stands up for a humane and inclusive vision, the long-term prospects for progressive politics could be better than they have been since Franklin Roosevelt allied with big-city Democrats to create the New Deal.

“Given the absence of Democratic Party leadership, either in the White House or Congress, there’s a little bit of a vacuum at the national level in the terms of leadership,” says Fordham University political-science professor Bruce Berg. “Now that nobody’s there, this might be a good time for [de Blasio] and other Democratic mayors to kind of assert themselves.”

Even so, priority number one for de Blasio is winning a second term, and another round of jet-setting around the country would hand his opponents a juicy talking point—so for now, expect him to wage his resistance from the 212 and 718 area codes. Even on that familiar terrain, however, de Blasio knows he has potent enemies. “There’s certainly still opposition from the hedge-fund world,” he told The Nation. “There’s opposition in the landlord lobby. There’s focal points of opposition—some elements of the charter-school community.”

✰ ✰ ✰

Of course, that isn’t the full roster of foes. De Blasio also has critics on the left, especially on the issue that boosted his campaign for mayor—police reform—and on his affordable-housing program, the policy that will anchor his legacy.

The use of stop-and-frisk has been dramatically reduced, arrests are down, city cops are slated to get implicit-bias training, and de Blasio’s new neighborhood-policing initiative aims to make individual officers more accountable to the communities they patrol. But a number of advocates, including the New York Civil Liberties Union and the Police Reform Organizing Project, have expressed alarm about the persistence of “broken windows” policing, especially since people of color experience the vast majority of arrests for “quality of life” crimes like turnstile-jumping and criminal trespass. “Broken windows’ time has passed,” said Queens Councilman Rory Lancman, speaking to the city’s outgoing police commissioner, Bill Bratton, when the latter defended the policing model this past fall. “It’s a model that’s harming police-community relations and safety in general.”

Advocates are also angry with de Blasio’s opposition to laws that would make police choke holds a crime and increase the New York Police Department’s transparency; the administration has pushed, instead, to deal with those matters through the NYPD’s internal regulations. He is “managing to lose both the cops and the left at the same time,” says Baruch’s Birdsell, “so that is not a winning issue for Bill de Blasio.”

On housing, the mayor has taken a number of humane and sensible steps, such as providing more lawyers to help tenants avoid eviction and orchestrating a two-year rent freeze on the rent-regulated apartments in which 1.6 million New Yorkers live. De Blasio’s housing plan, however, rests on giving the real-estate market what it wants—more density—and carving out a share of the new apartments for income-targeted housing. Local groups like New York Communities for Change believe that the new housing will trigger gentrification, washing out the impact of the new affordable units. They’re also alarmed that the “affordable” part of these projects will target households making as much as $130,000 a year in addition to those in much lower income brackets. Statistics show that the lack of affordable housing has reached crisis levels at the lower end of the income spectrum, and some advocates wonder why the city is devoting any amount of such a scarce resource to households who need it less desperately. Housing is where the disappointment with de Blasio seems deepest and most personal.

Fitzroy Christian, a tenant leader in the Jerome Avenue area of the Bronx, which de Blasio wants to rezone, shares that disappointment. “Our initial belief was that this was an opportunity for the city to start investing in a forgotten community—the Bronx,” he says. “Then we began to look at the implementation of the plan and realized that many people would not benefit. He may meet his [goal of] 200,000 units of housing, but it is not going to be 200,000 units of affordable housing.”

Both policing and housing are policy minefields, particularly for this mayor. Any rise in crime would validate every right-wing prediction that a progressive mayor would undermine two decades of progress against the city’s signature social ill. On the housing front, de Blasio inherited a huge distrust sown by his predecessor’s obliviousness to the toll inflicted by unchecked development on neighborhoods across the city.

But these dissenting voices reflect more than just the standard push and pull of politics. Instead, they embody real disappointment with how incompletely the mayor has fulfilled the vision he articulated as a candidate. How de Blasio goes about answering them over the next few months will say a lot about what kind of progressive alternative he presents to the right-wing populism of the president-elect.

De Blasio told The Nation that he’s proud of his record on police reform and wants to “deepen [it] on a whole host of levels.” But, he added, “there’s some elements of it that I’m going to be concerned with how to sequence properly, because I want it to stick. I want it to work with the day-to-day reality of the NYPD.… There’s waves upon waves of reform, and they have to be secured. They have to work.”

On housing, the mayor is adamant that his plan is better than the available alternatives. “We knew we could never subsidize our way out of the affordable-housing crisis. We needed a certain amount of private-market activity—with new ground rules, with new stipulations—to put up the maximum number of apartments. It might have been a legitimate or, in some ways, more pure position to just do fewer affordable apartments. What’s the more moral and correct thing to do? I came to the conclusion the goal was a huge number of apartments, and to maximize the number we could for the lowest-income families, because I thought we had an affordable-housing crisis that was reaching across the board.” What’s more, de Blasio said, low-income people benefit from the other steps he’s taken—such as providing legal assistance to tenants and working to shore up the New York City Housing Authority—in ways that middle-class residents do not.

“I’m never surprised by progressives who say we have not done everything that could be done,” he told us. He added: “There is a time to put the pedal down hard and do very fast, intensive change, and there are times when incrementalism is actually the more effective approach, the more lasting approach, and I mix and match those pitches all the time…. It doesn’t surprise me that some people come at it with a more absolutist, purist view.”

✰ ✰ ✰

By mid-December, as the spasms of revulsion at the prospect of a Trump presidency receded to a kind of steady nausea, trouble at home began to impinge on de Blasio’s national moment.

His child-welfare chief resigned after the death of one young boy from abuse, and ahead of the release of a scathing report on a similar death earlier this past fall. City Hall revealed that the mayor had made use of the expensive privilege of NYPD helicopter rides more often than he’d previously disclosed. Apparently hoping to sweep more unappealing news under a holiday rug, de Blasio’s aides partly complied with a long-standing Freedom of Information request on Thanksgiving eve, releasing e-mails that demonstrated the mayor’s close ties with lobbyists. And two infant girls were scalded to death when a radiator burst in an apartment that the city had rented from a notorious slumlord under a homeless-housing program.

It will be a difficult challenge for the mayor to take a leading role against Trump while dealing with these issues and running for reelection. The prospect of legal trouble will not make that job any easier. In mid-December, it was reported that two grand juries—one federal and one state—had been convened in investigations of the mayor’s fund-raising. If either returns an indictment of someone close to the mayor, it will be a serious blow to his credibility, stature, and ability to govern.

Despite all this, the tougher test that de Blasio faces may be fulfilling his own progressive promise, because that’s the real foundation his critique of Trump rests upon: the notion that inclusive policies that give everyone a share in progress are more effective than authoritarian xenophobia. That task was going to be challenging regardless of who ended up in the White House, because de Blasio won office largely by highlighting a problem—income inequality—that is impossible for a mayor to solve on his or her own. But a Trump presidency will make progress even harder.

“In a city like New York, where there are global interests present, maybe there are limits to how progressive a mayor can be?” posits Fordham’s Berg. “He’s got constraints, too.” But people like Christian, the Bronx tenant advocate, aren’t convinced: “He’s going to have to do a whole lot to bring me back. I don’t think the mayor is pushing his agenda as aggressively as he should.”

Days before anyone thought that his reelection campaign might have national overtones, de Blasio told us that he was looking forward to the debate. “My strong view is that we’re going to embark upon a real discussion in this city about where we’re going, and that it will generate a lot of interest. We think this is a golden opportunity, and…particularly because of social media, we have tools to have a deeper, fuller, more grassroots conversation about where we’re going.” He added: “There’s a huge constituency of Bernie supporters in this city that should be engaged civically…. That’s going to be a group that I very specifically reach out to.” (Indeed, de Blasio hired Sanders’s digital fund-raising team to help with his reelection campaign and recently brought on Michael Casca, Sanders’s rapid-response director, to run his City Hall communications team.)

Feeling the Bern and hating on Trump aren’t the only national political forces playing out in the city. The deep disaffection that working-class people expressed in the Rust Belt lives here, too. It’s what drives the skepticism among low-income New Yorkers regarding the mayor’s housing plan. That means it will take imagination and guts to square broad progressive ideals with the bricks and mortar of governing New York. Providing advice on immigration law to undocumented immigrants is wonderful, but less effective if they can’t afford a place to live.

“A thing progressives have to come to grips with in government is: You have to make your program work,” de Blasio said. “It can’t be ragged. It cannot be partial. It cannot fail. It has to work.” He’s on to something there.

Jarrett MurphyTwitterJarrett Murphy is the executive editor and publisher of City Limits.