How New York Can Help End the Global Debt Crisis

Economists Martín Guzmán and Joseph Stiglitz explain how state-level changes can assist the 3.3 billion people living in countries that spend more on debt service than healthcare.

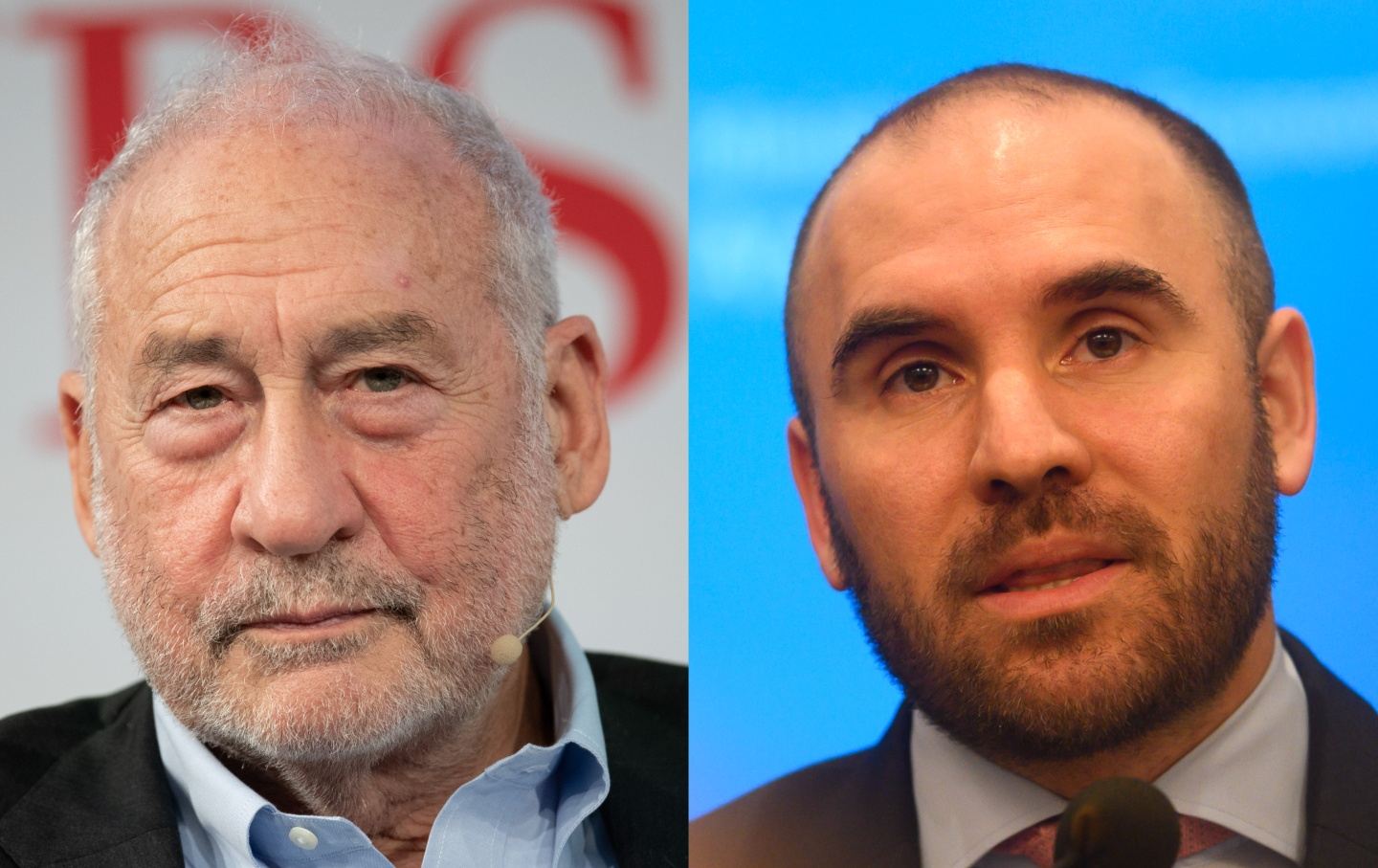

Joseph E. Stiglitz, left; Martín Guzmán, right.

(Left: Boris Roessler / picture alliance via Getty Images; Right: Manuel Cortina / SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)

In January, Columbia economics professors Martín Guzmán and Joseph Stiglitz published a report, “How New York State Lawmakers Can Help Address Debt Crises in the Global South,” to support legislative attempts to reform the state’s role in debt restructurings for countries with distressed economies. The report includes recommendations that legislation should blunt incentives for vulture funds, which profit from buying defaulted bonds and litigating full repayment through the courts, and reduce the interest rate accrued by creditors during the time between default and settlement.

These efforts are crucial, explain Guzmán and Stiglitz, because 3.3 billion people live in countries that spend more on debt service than on health. Countries with the highest debt load include Sri Lanka, Zambia, Ethiopia, Ghana, Ecuador, and Pakistan. Debt burdens can also prevent low- and middle-income countries from accessing international markets and lending, which limits their ability to secure investments for critical infrastructure, clean energy, and climate adaptation. Since about 50 percent of global sovereign bonds are issued under New York State law, the state is the world’s most important jurisdiction for debt restructuring.

Legislative reform would contribute to resolving ongoing debt crises in the developing world. This would lead to more stable economies that would ease migration pressures as well as mitigate global trade impacts that cause inflationary pressures and increase costly government aid to distressed countries, all of which can also have a cost for New York taxpayers.

The attempt to restore the “champerty” defense, which international debtors can use against vulture funds, has long faced pushback from Paul Singer’s Elliot Management. Champerty, derived from English common law, prohibits buying up debt for the sole purpose of suing to recoup it. Singer, a billionaire hedge fund manager and major Republican donor who pioneered the vulture fund model, had successfully lobbied for a 2004 New York State law that eliminated champerty for transactions over $500,000. While bills introduced in both the State Assembly and the Senate last year that address champerty and debt frameworks failed to pass, they are expected to be reintroduced this session.

I sat down with professors Guzmán and Stiglitz to discuss the roots and possible solutions to debt crises in the developing world; their involvement in the upcoming Jubilee Commission, which is cosponsored by the Vatican and Columbia’s Initiative for Policy Dialogue; and the specter of the Trump administration’s economic policies.

—Ed Morales

Ed Morales: Following the OPEC crisis of the 1970s and the 2008 economic crisis, there were major increases in global liquidity that saw investors search for bonds from less-advanced economies that offered higher yields at higher risk. What problems did this create?

Joseph Stiglitz: It’s a problem of volatility more than anything else. After 2008, the increased liquidity in the market flowed to developing countries. But then we start tightening up, as we did post-pandemic, and funds flow out. One of things that has been a recurrent feature of this era is instability of flows, and these unstable flows are like a wrecking ball to these economies. They lead to fluctuations in exchange rates, stock market crashes, real estate crashes. One of our concerns is that the framework of global financial markets of the post–Bretton Woods world has been particularly averse to developing countries. If there were a long-term supply of low-cost funds that could be used for long-term investments, that would be one thing. But that’s not the world we live in. It’s finance capital, and finance capital has been destructive.

Martín Guzmán: The gains have not been gains for the advanced nations per se. They’ve been gains mostly for the financial sector of those nations. And this has to do with the fact that the financial architecture is the outcome of power dynamics. When those who take capital to developing nations when there is abundant global liquidity face bad times, they manage to influence the International Monetary Fund to get a bailout, which is what is happening right now.

EM: How central is the problem of sovereign debt to the development crises in the Global South?

JS: In those countries where debt payments exceed health expenditures or education expenditures or take up a large fraction of foreign exchange revenues, it’s clearly contributed to the development crisis. Money spent on servicing foreign debt is money that’s not available for development, and that seriously encroaches on development and creates a crisis. Unfortunately, for a whole variety of reasons, a very large proportion of the debt that exists today wasn’t done for that kind of future-oriented prosperity. It has just led them to face a crisis in the future.

MG: The kind of financing that low-income countries that are in crisis receive is too short-term and too expensive. Everyone should have known that there was a high chance that this indebtedness will lead to trouble. Creditors want to be compensated for the risks they took, but now they should be contributing relief. And that’s proving to be very difficult.

EM: Is the lack of an international debt framework by design or an unintended loophole?

JS: It is part of this power dynamic. The powerful creditors like the ability to use power and fear to get terms and debt restructurings that are favorable to them. They sometimes make the argument that everything should be done within a contract. My response has always been, if you can solve these problems only through contracts, why is it in that our countries we have bankruptcy courts? It’s because you can’t solve this problem by contracts. Internationally, things are more complicated. You have problems like a conflict of laws. So the lack of that framework is the intended consequence of powerful groups not wanting a fair and equitable adjudication process.

EM: Why is there such a lack of commitment to due diligence before lending in bond markets?

JS: If you get bailed out, what is your incentive? The bailouts actually lead to a bad lending market. The incentives today of both creditors and lenders are to get more money out. The government gets money today and the problems of repaying are of a government 10 years from now. The lender is not a single person; it’s an institution, and the person who makes the loan gets a commission or gets a bonus based on how much money they’re shoveling out. They’ll be gone probably to a different company by the time the money comes due. So the whole structure is— both at the organizational level and at the individual level—one that doesn’t work well for due diligence.

EM: How are efforts to combat climate change intertwined with sovereign debt crises?

JS: Money that countries have to spend on development, on debt servicing the debt, is money they can’t spend on development. It’s also money they can’t spend on mitigating and adapting to climate change. The first priority, as it is structured now, goes to servicing the foreign debt. And obviously, developing countries, if they have money left over, are going to meet the basic needs of their people through shelter, education, and health. A global public good, which will affect all of us, will be squeezed out. That’s going to have global consequences.

EM: One of the things you’re calling for in the proposed legislation is to take away the motivation of lenders to delay debt restructuring. What’s the root of this strategy?

JS: What I would say is it’s mainly a result of what is called inter-creditor conflict, that each one hopes that the other guy can’t hold out. It’s a war of attrition. These are bargaining strategies that lead to dysfunctional outcomes. That’s one of the reasons why you need a court to say you can’t delay. You have to come in and resolve the issue. This is why more than half the debt restructuring since the 1970s have been followed by another within five years. After the delay, when you restructure, there’s too little and it’s too late.

EM: Vulture funds have thrived on the 2004 change in the champerty defense law. Do you think that your proposed reform of this law will face the most pushback?

JS: This has created a whole class of people whose business model was going to the courts and getting humongous returns by buying bonds that were very depressed and suing for full returns. It really undermined the whole functioning of the debt framework, which is why a lot of responsible lenders want champerty to be restored. They support some of the other reforms that we’ve been advocating, like the lowering the interest rate on pre-judgement interest rate from 9 percent to a more reasonable one, because that rate incentivized not resolving the debt issue.

MG: The 9 percent rate was set in 1991 when the inflation rate in the US was 8.9 percent, and it simply makes no sense whatsoever. But champerty created winners and losers. There are traders that have actually lost because of champerty, because if others get a higher share of the pie, the size of the pie gets smaller if the country can’t recover. It’s in the best interest of good-faith creators to reinstate a variant of champerty that rules out the vulture funds’ behavior.

EM: Beyond your advocacy for legislative reform, you are also involved in the 2025 meeting of the Jubilee Commission.

JS: We’ve been working with the Vatican on a project that had as its objective securing global cooperation on a multilateral approach to do something about not only this recurrent debt problem. We had a debt relief in 2000; it worked, but here we are 25 years later with another debt problem. I think among the countries of the world there’s strong support for this idea. It isn’t good for the global economy the way things are working. At the UN there’s been strong support, but we’re in a new world, where there is uncertainty about the ability of multilateral agreements. We hope that something can be done, but the signs so far are not positive.

EM: The idea of the Jubilee Commission seems to be in line with a shift to a framework around settling debts that is both moral and practical. But instead of allowing countries the ability to grow their economies to pay back debts to maintain global economic equity, the remedy has just been about imposing austerity.

JS: Standard prescriptions of austerity in response to debt crises has never worked. The exercise of power to force countries to undertake austerity measures, which they don’t want, I don’t see the current Treasury stepping away from that if it can get away with it.

EM: There’s been speculation that the BRICS alliance is posing a threat to US dollar currency. But at the same time, we see on the political stage, Modi comes to the White House and Trump appears to have taken Putin’s side in the negotiations to end the Ukraine War. How do you interpret that?

MG: For the international monetary system, I wouldn’t expect sudden changes. These are trends that are built over time. And the hegemony of the dollar is challenged by the growth of China in the global economy. But that is a slow process. China has become a lender of last resort for several countries, and China has abundant liquidity. The yuan has become a reserve currency, which is a major change for the international financial system. But again, this is not just about the BRICS, it’s about the growth of emerging economies in general and the growth of China. I would expect to see a different world 50 years from now, but not too different a year from now.

EM: How do the actions taken by the new administration make it more difficult for global finance to become more equitable and efficient, as you call for in backing this bill?

JS: We don’t yet know where Trump is going to go vis-à-vis tariffs on developing countries. Mexico has been the only example—and it’s an emerging market. The challenge of debt is earning revenues to service the debt. For developing countries, earning the revenues means selling mostly exports to advanced countries, and the US is the single largest advanced country. If the US says, “We’re not open,” and imposes tariffs, that means either they won’t be able to sell as much or what they sell they’ll sell at a lower price. In either case, their revenues will go down, and their ability to service the debt gets diminished. Making things even worse is all the uncertainty that we face has the effect of raising interest rates. Markets don’t like uncertainty, and they demand compensation. Interest rates are already exorbitant for developing countries, and this just raises them even more. The broader macroeconomic framework of Trump seems to suggest that there will be an increase in the deficit, and the tariffs will lead to higher interest rates, and that exacerbates the debt problem for developing countries.