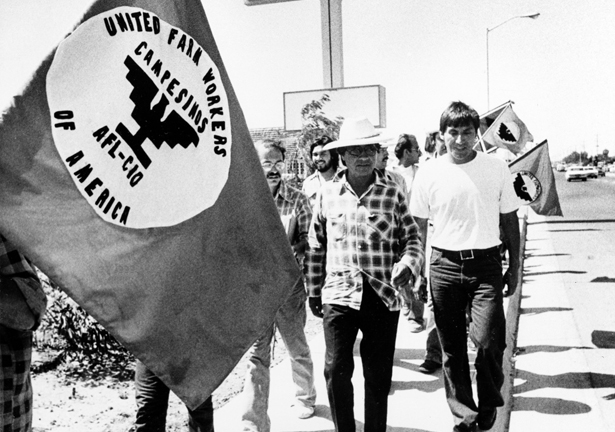

Cesar Chavez, in plaid shirt, marches with members of the United Farm Workers outside a Delano, California, supermarket, August 25, 1975. (AP Photo/Walter Zeboski)

The new biopic of Cesar Chavez makes me sad—and angry. To be sure, it draws needed attention to a key chapter in American Latino, labor and social movement history, as well as to the man whose leadership was central to it all. But it does so by reducing the man, the movement and its meaning to caricatures. The lessons the film teaches contradict the real lessons of Chavez’s work. And the “excuse” that “no movie can tell the whole story” doesn’t really wash. An earlier film in which director Diego Luna had an acting role, Milk, does the man, movement and meaning justice. There have been others—just not this one.

Cesar’s core leadership gifts were relational. He had an ability to engage widely diverse individuals, organizations and institutions with distinct talents, perspectives and skills in a common effort. The film, however, depicts him as a loner: driving alone (when in reality he had given up driving), traveling alone (which he never did) and deciding alone (when his strength was in building a team that could respond quickly, creatively and proactively to the daily crises of a long and intense effort).

Cesar was an organizer’s organizer, the craft in which he prided himself. This required a focus on people, their strengths and weaknesses, the dynamics of power and work behind the scenes. In the film, he gives speeches, which he avoided, and engages in shouting matches on the picket line, which he never did. A believer in the rhetoric of action for many years, he rarely held press conferences, speaking to the public instead from the scene of the action.

Cesar could be a brilliant strategist, a skill observable in agile, imaginative interaction with determined opponents, turning apparent weakness into sources of strength. But the film depicts him largely as a creature of impulse, committed to be sure, but not the brainy strategist who took special joy, as he put it, in “killing two birds with one stone…and keeping the stone.” He was a learner, a deeply curious autodidact who thrived on constantly probing diverse sources of information: books, people and experiences. When I met him in 1965, he was reading Churchill’s The Gathering Storm because, as a student of Gandhi, he wanted to learn how his opponent thought. The commitment to nonviolence was based both on his appreciation of Gandhi’s methods and the way in which the civil rights movement, and reaction to it, had been unfolding every day. But oddly, although a commitment to nonviolence was a condition for undertaking the strike in the first place, shaping the way it unfolded, the film portrays nonviolence as a reaction to events in the strike.

Events depicted as spontaneous in the film, such at the 1966 “perigrinación” from Delano to Sacramento, were, to the contrary, a result of sustained, careful planning. The “kick-off” was timed to take advantage of national media in town to cover Senator Robert Kennedy’s participation in hearings held in Delano, orchestrated by the labor movement. This “march” strategically linked efforts to promote the UFW’s first boycott, to deter farm workers from returning to Delano in the spring, to pressure then Governor “Pat” Brown to intervene on the UFW”s behalf and to rekindle the faith, hopes and solidarity of the 100 to 200 people at the core of the movement and their supporters. Cesar did not hear of RFK’s death while driving somewhere in his car—we had been in LA doing the “get out the vote” that won him the primary, and some of us were with him in the ballroom when he was shot, on his way to thank the farm workers for their help. Similarly, the “fast” was not a reaction to a few unruly farm workers but a strategic tactic, backed with a team of organizers, of which I was one, undertaken at a key time in response to court actions alleging violent tactics, renewing commitment several years into the fight and drawing attention to the grape boycott in time for the new season. The creativity, organizational discipline and courage that produced the events depicted in the film is lost entirely in the incoherent jumble of what the film makers must have judged to be “dramatic moments,” which presented out of time, place or sequence are robbed of their real drama.

Cesar was a man who understood the power of culture so well that he not only rooted the movement in the richness of his own Mexican religious and cultural traditions but did so with a commitment to the strong pluralism, albeit imperfect, that building a union would require. Filipino workers began the strike. The African-American civil rights movement was a key source of ideas (the boycott, for example), volunteers and inspiration—a fact the film ignores. The American labor movement, in the person of the UAW’s Walter Reuther and the AFL-CIO’s Bill Kircher, provided critical funding, support and political backing. Senator Robert Kennedy’s engagement was part of a broader effort to gain the support of liberal Democrats. White Protestant clergy, two of whom were among Cesar’s closest colleagues, James Drake and Chris Hartmire, are hardly visible in the film. And the US Catholic Bishop’s Committee, who actually mediated the grape contracts that resulted form the boycott, are entirely ignored.

The first person to lose their life on a farmworker picket line was not Juan de la Cruz, as the film reports, but Nan Freeman, a young Jewish woman from Boston killed while picketing in support of a UFW sugar strike in Florida in 1972. And it was Nagi Daifullah, one of a community of Yemeni workers who joined in 1970, who was clubbed to death by a Kern County Deputy Sheriff two days before Juan was killed, and his was the first large farm-worker funeral, a Muslim one, held in Delano.

Cesar thrived on diversity in his choice of mentors, collaborators and institutional allies, but the film portrays him as almost entirely dependent on his family and his early Latino associates, Dolores Huerta and Gilbert Padilla. The exceptions are a ridiculously hippy version of lawyer Jerry Cohen and a strangely curmudgeonly portrayal of Cesar’s organizing mentor Fred Ross. That the filmmakers ignore Cesar’s capacity to engage all this diversity—not in denial of his own culture but on the strength of it—is inexplicable.

The significance of the farm worker movement was quite real for a period of some fifteen years, enhanced by its role as a crucible for training a new generation of organizers who contributed to the progressive movement more broadly, and, in particular, as a spark for the broader Chicano movement, linking aspirations of a rising generation, like the young men and women who led the East Lost Angeles school “walk-outs” in 1968 (as excellently portrayed in the HBO special of the same name), those who formed MECHA (Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Atzlan) in 1969 and others.

But then it ended.

And although the role of the volunteers who staffed the first boycott is invisible in the film, the farm workers themselves seem to serve only as props. What difference did this movement actually make in their lives? What did it mean to actually have a union as opposed to not having one? And what happened to them? California farm workers today are in even worse shape than when Cesar’s struggle began. There is no union to speak of any more, nor has there been for years. And one of the principal reasons for this decline turned out to be Chavez himself, the limitations of the organization we built and painful consequences of so many years of struggle. Historical perspective is one thing, but sentimentalized nostalgia about the “voices of the poor being heard” is something quite different.

It is too bad that the authors of this project failed to appreciate the seriousness of the undertaking, the complexity of the man, the character of his organization, the nature of the movement he built and, most importantly, the opportunity for teaching, learning, inspiration and understanding that, sad to say, this film fails to meet. Chavez was a public leader, not only a private individual. And while the tension between him and his eldest son is interesting (a son who, by the way, refused military induction as a conscientious objector, a moment of great pride for his father that is omitted from the film), it is too bad that the current biases of his family, who held a veto over script, and the unstated agenda of those who made and funded this film, seem to have shaped this interpretation of the man’s public work.

Marshall GanzMarshall Ganz worked on the staff of United Farm Workers for sixteen years. A political organizer, he is a senior lecturer in public policy at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.