We’ve come a long way over the six years since Congress began crafting the Affordable Care Act. We’ve traveled from death panels to death spirals, passing through nearly 60 House votes on ways to repeal or gut the law, at least one election defined by it and two Supreme Court challenges to it. But finally, with the Court’s definitively worded ruling in King v Burwell, we may have arrived someplace hopeful: the beginning of a meaningful debate over the law’s role in fixing our broken healthcare system.

There is plenty to debate. The right’s obsessive focus on Obamacare’s repeal has been maddening for many reasons—the dishonesty that has defined its critique, the way it has leveraged disturbing ideas about the president’s legitimacy—but among the most frustrating side effects has been its impact on the urgent work of improving the law. Everyone has been too occupied with arguing over Obamacare’s very existence to truly watchdog its implementation—and its many potential pitfalls. The law is, still, predicated on the idea that healthcare is a consumer product rather than a public good. And even in its most successful manifestation, the Affordable Care Act will by design leave out millions of people who live in this country and, their immigration status notwithstanding, depend upon our health system.

So let’s get back to basics: The United States has the most expensive healthcare system in the world, delivering the least effective results among its would-be peers of wealthy nations. That’s been true for a very long time. One big reason for the system’s colossal failure has been that tens of millions of people only enter it once they are in crisis—meaning they are both more expensive to treat and less likely to have healthy outcomes from that treatment. As the Court’s ruling deftly summarizes, the Affordable Care Act aims to fix this problem by making insurance more cheap, more fair and mandatory. Is it working?

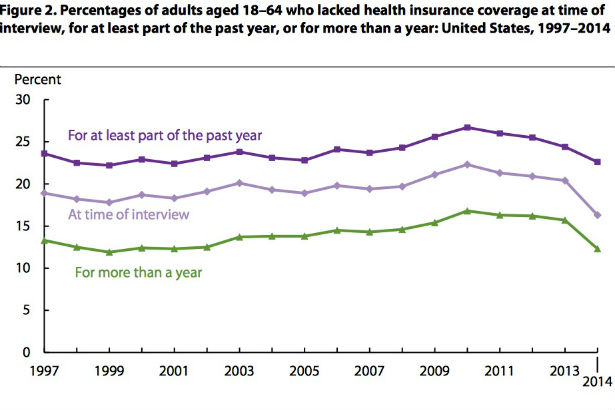

There’s little question the law has worked in its core goal of expanding the number of people who have insurance. The uninsured rate among non-elderly adults began dropping as elements of the law took effect in 2010 and fell off a cliff once it was fully implemented. After years and years of handwringing over steady growth in the ranks of the uninsured, Obamacare turned the clock back. The share of our population without coverage dropped by more than 4 percent last year, a Centers for Disease Control study found, arriving at a lower rate than the CDC has seen since before 1997.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →But there remain significant political and regulatory fights if we are to translate this accomplishment into a functioning and equitable healthcare system. Here are three.

1) Fix Medicaid Everywhere

The right has obsessed over the individual mandate, but Obamacare’s real radical change has been the historic expansion of public health insurance for the poor. A major reason for the uninsured rate’s drap nationally is Medicaid’s expansion in a little over half of the country. In the 21 states that still refuse to open up their Medicaid programs, roughly one in five people remain locked out of our healthcare system. Everywhere else, the uninsured rate has been cut to just over 13 percent.

As I’ve written, these statistics sanitize political choices that have fatal consequences. The states that remain outside of the new Medicaid system are all controlled by Republican legislatures—many of which swept into power on the back of scare-tactic campaigns focused on Obamacare in 2010 and 2012. It is shocking just how poor one must be to qualify for public health insurance in those states. As of January 2015, the median qualifying limit for parents was 46 percent of the federal poverty level. That means parents in a family of three who made $10,000 a year were too rich to get help, too wealthy to have options beyond turning up at the emergency room when crisis strikes.

This disparity is the Supreme Court’s fault. In its 2012 ruling on Obamacare, it shocked even the law’s critics with an out-of-nowhere decision that Medicaid expansion was optional for states. That means the problem can be fixed only by forcing political change in the red-state legislatures that still refuse to acknowledge the existence of the Affordable Care Act. An election approaches, but it’s hard at this point to imagine Medicaid expansion will be among the defining debates. That’s a shame.

2) Make Coverage Meaningful

There is a difference between having insurance and having access to adequate healthcare. And for the just over 10 million people who have bought Obamacare plans, there are real questions about whether insurers are actually providing a fair deal.

Republican critics have advanced the claim in recent weeks that premium rates are spiking in Obamacare marketplaces. That’s at best a partial truth. Rates have indeed climbed in some places as insurers have searched for the right price point, but markets vary widely and, overall, most are seeing only modest increases. In any case, the premium-hike discussion is a distraction from the real problem.

In fact, during the first two years of the law, insurance companies have competed fiercely on premiums at the low end of the market. It turns out that consumers shop the healthcare exchanges much like they do a restaurant wine list—they go with the second-least expensive option among a bunch of overwhelming, poorly understood choices. So for insurers, the complicated business of setting premiums has been about winning at this price point. And that means shifting the cost of care itself to consumers. This is a trend that began in the market for employer-based plans and has continued in the exchanges.

As a consequence, patient advocates reported alarming amounts of sticker shock in the first year—particularly among patients who most needed care. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, autoimmune disorders, cancers, HIV—all the things that were problems in the old system, were proving problematic in the new one. “We’re really getting a kind of flood of this particular issue,” Brendan Beitry, a case manager with the Patient Advocacy Foundation, told me as patients first started using their new coverage last summer. “They’re contacting us from their oncologists’ office or their doctor’s office, or after they’ve got off the phone with a specialty pharmacy and they’re delivered the blow of cost.”

Overall, one in four people with coverage purchased on the exchanges went without care last year, because they couldn’t afford it, according to a Families USA analysis. Fifteen percent skipped tests or follow up treatments. Fourteen percent skipped prescriptions. The problem, of course, is healthcare is not like wine. If the second-cheapest choice is the wrong one for you, it’ll ruin more than dinner.

3) Make Regulators Do Some Regulating

The standard response to the sticker-shock problem has been that consumers need more information, and the law certainly makes that information more readily available than it was in the past. But if we’re going to keep treating health as a product, the onus for making it a truly fair and affordable one will need to be on those who regulate the market, not on those who shop in it. The morass of co-insurance versus co-pay, of tiered formularies and providers, of changing and narrowing networks, it is all designed to conceal the basic fact of cost-shifting from insurer to patient. That was true before Obamacare and remains true now, and there will be no substitute for close, aggressive regulation of these products.

Which again brings us to the states that refuse to acknowledge the law’s existence. Health insurance markets are hyper-local, and they require local oversight. But in places where the political leadership refuses to engage, there’s every reason to believe that oversight is lacking. These markets are confusing and overwhelming, and thus ideal for disastrous exploitation—see under subprime mortgages. States have their work cut out in making them function well, in the best of circumstances. Let’s hope we can all now turn our attention to that massive challenge.