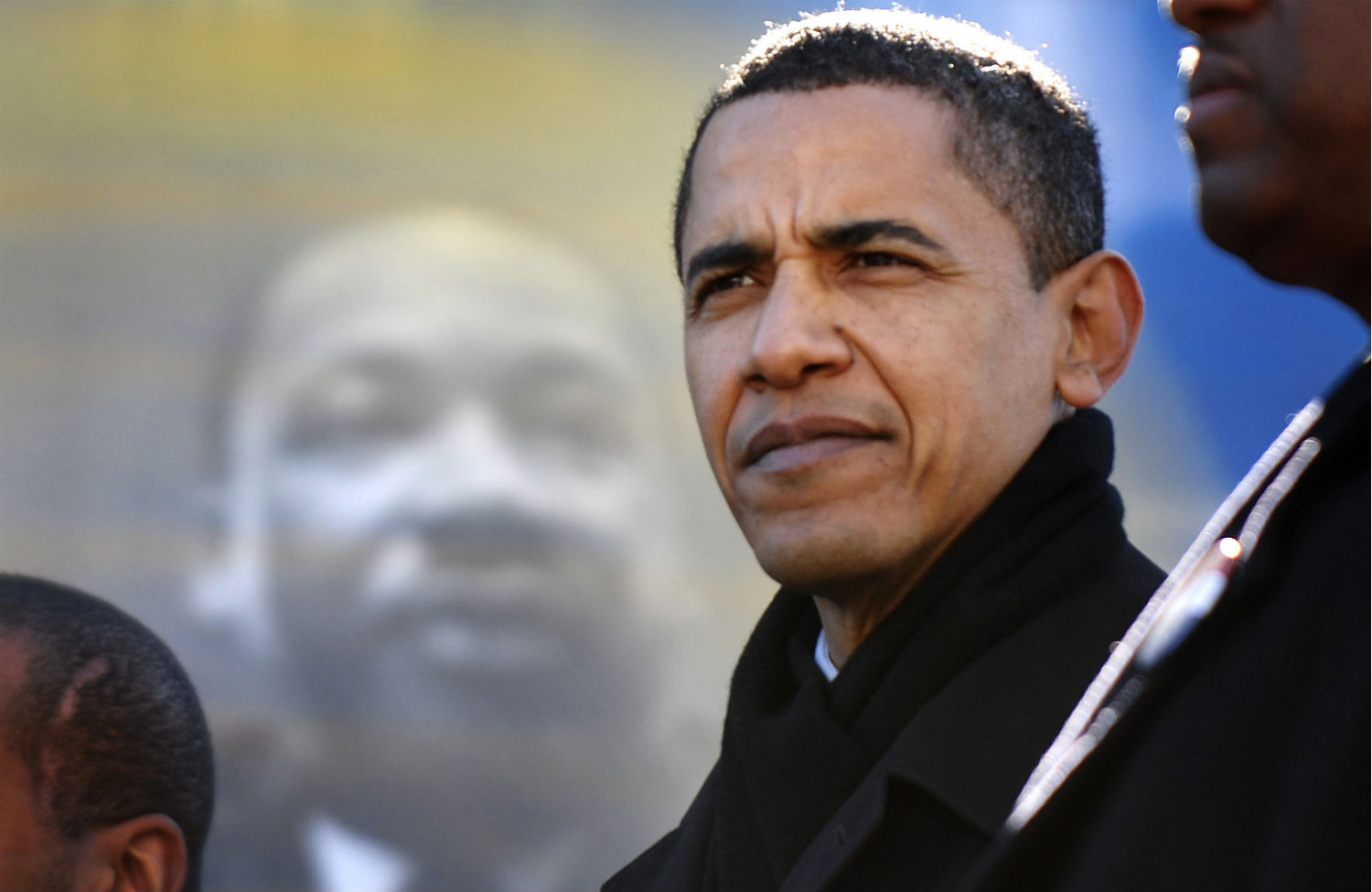

Despite his best efforts to be the embodiment of respectability, it turns out Barack Obama is a role model for resistance.

Melissa Harris-Perry

(Reuters/Jonathan Ernst)

The protests in Ferguson, Missouri, after police officer Darren Wilson killed unarmed teen Michael Brown were Barack Obama’s fault.

This is not a claim about law enforcement’s continued militarization under his administration. The federal government has been engaged in arming local police with the weapons of war for more than a decade. Further, the White House must be credited with announcing a decision to review the distribution of army surplus to local police forces and to consider limiting it in the future.

This is also not a claim about the president’s decision to remain ensconced on the golf courses of Martha’s Vineyard as unrest exploded in Missouri’s streets. The optics of a vacationing president set against the breathtaking images of local police bearing down on American citizens with riot gear were discordant and deeply troubling. So too were the president’s lukewarm equivocations. But the administration must be credited with deploying Attorney General Eric Holder to the scene. Holder’s visit successfully conveyed the seriousness of federal authorities seeking both to calm the immediate crisis and to pursue justice in the case of Michael Brown.

This is not a claim about the president’s inability to rein in the provocative choices of his fellow Democrat, Governor Jay Nixon. Surely Obama must have known that imposing a curfew on protesters and calling up the National Guard would ignite the righteous rage of organizers. Perhaps he bears political culpability for not dissuading the tone-deaf Missouri governor from escalating the crisis. But, ultimately, if any national Democrats are responsible for foisting Jay Nixon into the office from which he could make those choices, it’s Bill and Hillary Clinton, who have been public supporters of Nixon and cozy partners with him for years.

Still, despite Obama’s equivocations—and also somewhat against his will—the protests in Ferguson, Missouri, were his fault. And he should be proud.

The people of Ferguson and those in solidarity with them took to the streets within a context of racial repression broader than just one horrific shooting. Between 2005 and 2012, African-Americans have been killed by white police officers at the rate of nearly twice a week. In the month preceding Brown’s slaying, police in this country killed at least four unarmed black men. And in a state like Missouri, African-American drivers are the targets of 92 percent of vehicle searches conducted by police, even though illegal items are found in less than 25 percent of these searches.

The fact that Barack Obama is the president of the United States is the most tangible daily reminder that black people are full citizens of the United States, endowed with the same inalienable rights as their fellow Americans, and capable of exerting their political will to bring forth the political and policy outcomes they prefer. President Obama is the contemporary embodiment of the astonishing possibilities of black citizenship. He can be faulted—or rather credited—with helping ignite the refusal of black citizens to be relegated to second-class status in the wake of Brown’s slaying.

Senator Obama was a long shot when he chose to challenge the powerful Clinton machine for the Democratic nomination. He triumphed because of strategy, audacity and the overwhelming support of ordinary black voters, even when they chose him against the advice of their longtime elected officials, who remained firmly in Clinton’s camp. That experience was an object lesson for black Americans: they could choose for themselves. Perhaps that memory was embedded in those who resisted the curfew imposed by a Democratic governor as their black congressman stood at his side.

During the 2008 general election, Senator Obama rarely spoke about racism directly, but he endured it and bore up under it. Indeed, he inspired a multiracial, intergenerational coalition that included states of the former Confederacy to carry him into the White House. He brought along with him the symbolic possibility of full inclusion. In 2012, President Obama’s re-election in the context of massive efforts to suppress African- American voters made it clear that black people were unwilling to cede the ground they had gained in asserting their political will.

No matter what his policies, his politics or his public pronouncements, Barack Obama changed the relationship of African-Americans to the American state. Even as they were forced to endure the images of Michael Brown’s lifeless body lying in the street for hours, many black Americans see in President Obama’s living presence in the halls of power a stark reminder that another outcome is possible for black men if their communities refuse to be silenced.

Since his early days on the national scene, many have wanted Barack Obama to serve as a role model for black people. Obama himself has embraced this calling, launching My Brother’s Keeper as his presidential legacy project [see Dani McClain, in this issue]. Through My Brother’s Keeper, he hopes to model a careful conformity to the narrow rules of good behavior: commitment to education, decent employment and other middle-class achievement markers. But along the way, he has modeled something he may not have intended.

The election of Barack Obama is a model of what’s possible when black people refuse to stay in their assigned places, when they demand more say in the system. He is president less because of his individual accomplishments than because his community was determined to see him assume a position of power. They mobilized repeatedly on his behalf even when they were told not to. (Emanuel Cleaver and John Lewis both backed Hillary Clinton in 2008 and were overcome by their constituencies.) Michael Brown’s community learned these lessons well.

Despite his best efforts to be the embodiment of respectability, it turns out Barack Obama is a role model for resistance. Yes we can. Read more from our special issue on racial justice

Mychal Denzel Smith: “How Trayvon Martin’s Death Launched a New Generation of Black Activism”

The Editors: “Renewing the Struggle for Racial Justice, Post-Ferguson”

Paula J. Giddings: “It’s Time for a 21st-Century Anti-Lynching Movement”

Rinku Sen: “As People of Color, We’re Not All in the Same Boat”

Dani McClain: “Obama’s Racial Justice Initiative—for Boys Only”

Frank Barat: “A Q&A With Angela Davis on Black Power, Feminism and the Prison-Industrial Complex”

Melissa Harris-PerryTwitterMelissa Harris-Perry is the Maya Angelou Presidential Chair and Professor in the Department of Politics and International Affairs and the Department of Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Wake Forest University. She is also the co-host of The Nation’s System Check podcast.