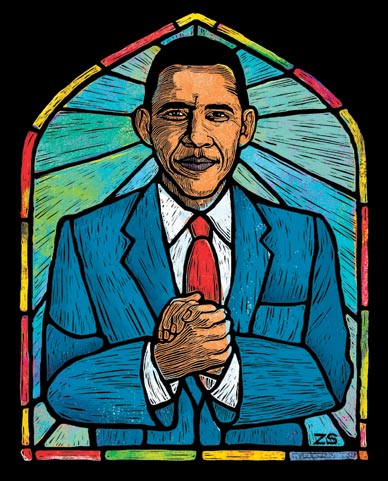

ZINA SAUNDERS

ZINA SAUNDERS

When President Barack Obama announced the appointment of Alexia Kelley, executive director of Catholics in Alliance for the Common Good (CACG), to lead the Center for Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships at the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), many progressive activists were alarmed. Kelley, a Catholic social justice advocate who has said that abortion is a social ill to be combated along with torture, poverty and war, is on record supporting restrictions on abortion access and has refused to challenge church doctrine prohibiting abortion and birth control.

Writing in Salon, Frances Kissling, former president of Catholics for Choice, lauded Kelley as “a distinguished advocate of healthcare reform and the rights of poor people” who “has much to offer in government–but not at HHS.” Jon O’Brien, current president of Catholics for Choice, stated publicly, “We need those working in HHS to rely on evidence-based methods to reduce the need for abortion…unfortunately, as seen from her work at CACG, Ms. Kelley does not fit the bill.”

For progressives, secularists and feminists, Kelley’s appointment is the latest in a series of alarming developments at the White House’s Office of Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships (OFBNP), which oversees a network of faith-based and neighborhood partnership centers at eleven federal agencies (including the one Kelley will head). During the presidential campaign, Obama said he would expand George W. Bush’s faith-based initiatives because “the challenges we face today…are simply too big for government to solve alone.” But he also promised to end the constitutional violations of Bush’s faith-based programs by requiring that federal dollars that go to churches, temples and mosques “only be used on secular programs” and by forbidding programs that accept federal money from proselytizing or discriminating against people in hiring on the basis of religion.

Since he has taken office, however, Obama has backtracked or stalled on these pledges. Perhaps more disturbing, Obama’s OFBNP, while still a work in progress, is plagued by a lack of transparency and accountability and has seemingly already been exploited as a tool for rewarding religious constituencies with government jobs–exactly the problems that marked Bush’s faith-based initiative.

Indeed, the structure of Obama’s OFBNP looks quite similar to Bush’s: a White House office (now under the direction of 26-year-old Joshua DuBois, the former religious outreach director of the Obama campaign) guides the project overall. Mara Vanderslice, founder of the Matthew 25 PAC, which supported Obama, works with DuBois. In addition, the centers at federal agencies oversee the disbursements of grants to faith-based and community nonprofits, some of which will, in turn, train faith-based organizations.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

The Obama administration has said the project will not just dole out money; it also intends to form nonfinancial partnerships with faith-based and community groups to deliver social services. But the financial relationships remain. For example, although Obama’s 2010 budget eliminated the Compassion Capital Fund, the pot of money administered to faith-based groups through HHS in the Bush era, $50 million has been authorized in the stimulus bill for a new Strengthening Communities Fund, which will be disbursed to nonprofits and state, city, county and tribal governments to train faith-based and other nonprofits to help “low-income individuals secure and retain employment, earn higher wages, obtain better-quality jobs and gain greater access to state and Federal benefits and tax credits.”

Watchdogs are concerned that, as with Bush’s fund, controls are insufficient to ensure constitutional protections, transparency or accountability. “These problems will persist until this administration stops operating under the Bush-era executive orders and regulations that still govern the faith-based programs,” says Marge Baker, executive vice president of People for the American Way.

Within particular federal agencies, many other grants are available to faith-based organizations, which compete for funding with secular organizations on the Bush-era “level playing field.” At HHS, under Alexia Kelley’s purview, tens of millions of dollars in grants are available to faith-based groups for projects including substance abuse treatment, mental health services, HIV prevention, family planning and even research on the influence of religiosity and spirituality on health-risk behaviors in children and adolescents. Although the Obama administration eliminated federal funding for abstinence-only sex education, the HHS website directs potential grantees to abstinence-only funding available through state governments.

At the Department of Housing and Urban Development, for example–where Obama has placed his campaign’s Catholic outreach guru, Mark Linton, at the helm of the faith-based center–religious organizations are invited to apply for a variety of housing-related grants. At the Justice Department the faith-based office advertises grants available to faith-based groups to “provide assistance to victims of crime, prisoners and ex-offenders, and women who suffer domestic violence [and] initiatives to target gang violence and at-risk youth.”

Moreover, by appointing former campaign staff to faith-based posts, Obama risks the appearance of politicizing the effort, something Bush and Rove notoriously did. “The only way to avoid the appearance is to do it differently,” says the Rev. C. Welton Gaddy, president of the Interfaith Alliance, a religious liberty and church-state separation watchdog group. “The White House needs to be reminded of that. They’re naïve if they assume that people aren’t going to look at that.”

The Rev. Irene Monroe, an LGBT rights activist and doctoral candidate at Harvard Divinity School, says, “It makes sense, in a political sense, to keep Joshua [DuBois]. He’s made these contacts. It’s not about effective change. It’s about, How do I keep that voting bloc?”

Although Kelley did not work on the Obama campaign, CACG was described by Katie Paris, communications director for the Democratic-leaning Faith in Public Life (FPL), as having had a “very aggressive engagement in this election cycle.” The co-founder of CACG, Elizabeth Frawley Bagley, who helped the Obama campaign reach out to Catholics, is now the State Department’s special representative for global partnerships and is working on global interfaith relations.

After the election FPL and CACG helped promote the idea that Catholics were crucial swing voters who shifted to Obama. Michael Sean Winters, author of the book Left at the Altar: How the Democrats Lost the Catholics and How the Catholics Can Save the Democrats, wrote about Kelley’s HHS appointment, “As well as helping faith-based organizations get funding for their programs, she will serve as liaison between the Churches and the administration.”

church-state separation advocates would prefer to eliminate the faith-based office entirely. But knowing that Obama was intent on keeping it, they supported him because of his campaign promises to reverse the most egregious aspects of Bush’s policies. But Obama has reneged on his pledge, made in a July 2008 speech in Zanesville, Ohio, to undo Bush-era rules permitting direct taxpayer funding of religious institutions and allowing institutions that receive federal grants to engage in hiring discrimination based on religion.

On the direct-funding question, Obama is “encouraging,” but not requiring, grant recipients to form secular nonprofits in order to receive federal aid. He punted on the hiring issue by referring questions on a “case-by-case” basis to White House and Justice Department lawyers; DuBois will help decide which cases are referred for legal evaluation. In addition, although Obama promised to end proselytizing by faith-based grantees, no policy sets forth rules against proselytizing or a method of enforcing them.

DuBois has promised a full overhaul of the White House OFBNP and federal agency faith-based, neighborhood partnership centers to increase the accountability of grant recipients and to monitor proselytizing, and he pledges to make clear to grant recipients “what the boundaries are.” But defining what counts as proselytizing, never mind monitoring instances of it in hundreds of federally funded programs across the country, is a daunting task. In subsequent press conferences, DuBois has been vague about how he will establish or monitor such boundaries. (DuBois declined to be interviewed for this article, and the White House press office did not respond to repeated requests for comment.)

“I am very disappointed that President Obama’s faith-based program is being rolled out without barring evangelism and religious discrimination in taxpayer-funded programs,” says the Rev. Barry Lynn, executive director of Americans United for Separation of Church and State. “It should be obvious that taxpayer-funded religious bias offends our civil rights laws, our Constitution and our shared sense of values.”

Sean Faircloth, executive director of the Secular Coalition for America (SCA), says, “The president has yet to implement his stated policy, so today government funds can still be used to discriminate based on religion or lack thereof. That’s unconstitutional.” Americans United and the SCA, along with other members of the Coalition Against Religious Discrimination (CARD), a network of civil liberties groups, have been urging Obama to repeal the Bush rules.

Among religious progressives, the dissatisfaction runs deep. The case-by-case rule “doesn’t offer much assurance for people who are concerned about discrimination,” says the Interfaith Alliance’s Gaddy, also a CARD member. “What is it that you have to see to decide not to discriminate?” The White House recently appointed Gaddy to a task force to recommend how to improve the “constitutional and legal footing” of the office, but the question of hiring discrimination, he says, is not on the agenda.

Center-right religious activists, assiduously courted by Obama during the campaign, see the hiring question differently. The ability to engage in what they call “co-religionist” hiring–for example, not hiring a gay applicant because his sexual orientation violates the organization’s religious beliefs–is central to their mission of providing faith-based services, they insist. Without that ability, they have no interest in the faith-based initiative.

After Obama’s Zanesville speech, these activists pressured his campaign to reverse course. In response, the campaign quietly promised religious activists that Obama would keep the Bush rules in place. As the Rev. Tony Campolo, who served on the DNC’s platform committee, wrote in the Huffington Post earlier this year, the Obama campaign sought to “still the anxieties” of leaders of some of the “largest faith-based organizations in the country” by “giving assurances that if no fuss was made by drawing attention to these problems, the policies that were in place on these matters during the Bush Administration would be continued.”

It is this constituency–center-right evangelicals and Catholics–that Obama continued to appease through the creation of a twenty-five-member advisory council to the OFBNP. The council’s mission is to provide policy guidance on poverty, abortion reduction, responsible fatherhood and global interfaith relations. Church-state separation advocates see the council’s mandate, which frames major policy issues in religious terms and institutionalizes an outside council of advisers, as a step beyond even Bush’s faith-based initiative. “This council either comes dangerously close, or it is a kind of institutional intertwining of religion and government,” says Gaddy.

Kissling calls the OFBNP’s mandate to address abortion “shocking.” Expanding the role of the faith-based office to include abortion policy “sends a very clear message about what the administration thinks religion is and what the philosophical underpinnings of the administration’s approach to abortion is. The administration’s approach is religious.”

The Rev. Peter Laarman, executive director of Progressive Christians Uniting, maintains that the advisory council’s to-do list is aimed at placating conservatives, not advancing a progressive religious agenda. “They are issues of primary concern to religious conservatives, and even poverty reduction has a conservative framing. I mean, why aren’t religious leaders being asked for advice on progressive taxation? On how to deal with big money in politics?… Those to me are issues with as much or more religious significance as supporting stable family life.”

While some on the OFBNP’s advisory council, notably Sojourners founder Jim Wallis, have claimed the mantle of “religious progressive” and, more recently, “religious left,” the bona fide religious left has largely been sidelined. When you look at the composition of the council, says Laarman, you see that “these were highly strategic selections with a view toward rewarding or cultivating very specific faith groups. With a couple of exceptions, hard-core religious progressives aren’t there.”

Of the first fifteen advisory council appointments, made February 5, only one was prochoice, and more, including a Catholic and a Southern Baptist, were ardent opponents of legal abortion. Two months later, when the White House filled out the remaining ten appointments, it added prochoice religious voices, but they were not from the ranks of the most prominent activists on abortion, such as representatives of the Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice. Opponents of LGBT equality also outnumbered gay-rights proponents, although the administration later added Harry Knox, director of the Faith and Religion Program at the Human Rights Campaign.

Center-right abortion-reduction proponents, however, have had an easier time securing a hearing. When David Gushee, a professor of Christian ethics at Mercer University and one of the most prominent voices from the evangelical center, complained publicly that Obama was not doing enough to fulfill his pledge to reduce abortions, he immediately received a call from the White House. “I regularly, weekly, get invited to come to the White House for a meeting or to listen or participate in a conference call on a range of things,” Gushee told me.

Gushee was the principal author of a 1996 manifesto, The America We Seek: A Statement of Pro-Life Principle and Concern, signed by forty-five religious-right leaders as well as advisory council member Wallis. It posited that it was unlikely Roe v. Wade would be overruled, and called instead for criminalizing doctors who perform abortions (but not “women in crisis”), opening more “crisis pregnancy centers” and passing a constitutional amendment overturning Roe and giving fetuses personhood status. Gushee said recently, “The principles articulated in this statement still reflect my own views.”

Reproductive rights activists remain optimistic that Obama will ultimately back a policy that focuses on preventing unintended pregnancies through comprehensive sex education and contraception, along with economic support for women who choose to carry unintended pregnancies to term. The White House’s policy discussions on abortion focus on “best practices” for reducing abortion; overturning Roe is off the table. Still, Obama has invited hard-right antichoice organizations like Concerned Women for America into these conversations, as well as advocates of the Pregnant Women Support Act, a bill backed by Democrats for Life and Alexia Kelley. The bill aims to influence pregnant women to “choose life” by bolstering social services for them, but it provides no funding for contraception or sex education.

OFBNP’s plan to go into partnership with faith-based groups through federal agencies is premised on the notion that these groups are indispensable to solving problems ranging from healthcare delivery to poverty. “We can’t solve these challenges here in Washington,” DuBois has told faith groups, echoing Obama’s campaign rhetoric on the importance of faith-based programs. Likewise, Jim Wallis has said, “There is more experience and expertise and relationship there in the faith community than in the departments of HHS, HUD and Labor and all that combined,” a position he has since extended to include the CIA and the State and Defense Departments. Wallis may have overstated the case, but even many progressives agree that government partnerships with faith-based groups are essential to delivering social services, a practice promoted by Bill Clinton through his charitable choice program. Columnist E.J. Dionne and church-state separation expert Melissa Rogers (who serves on the advisory council), for example, accepted that premise in a December Brookings Institution report recommending changes Obama should make to the Bush program.

Frederica Kramer, an independent social policy consultant to the Urban Institute who is working on a book about faith-based organizations, contests this logic. “There’s no empirical basis from existing research and evaluations to say that faith-based groups are better at delivering services,” she contends. Kramer says that while faith-based organizations play important roles, such as the disaster response after Hurricane Katrina, “one doesn’t want to mistake access like a congregation has for the ability to deliver long-term, professionally based services.” Kramer adds that reliance on faith-based organizations poses “the question of what happens to non-adherents or outliers.”

Calling the boundaries between the faith and secular content of programs “very porous,” Kramer says that eliminating proselytizing is a challenge. “Vulnerable populations are not well positioned to make choices–particularly children, people in court-ordered treatment programs and people with mental health problems.”

Another monitoring issue the project faces is untangling faith-based funding streams from general ones. Rob Boston, of Americans United for Separation of Church and State, says, “Rules against earmarking money specifically for faith-based projects–which would be illegal–have created a situation where grants going to faith-based organizations can be masked.” As a result, it is hard to know whether federal grant money–disbursed through block grants to states–is being used for faith-based projects and is therefore subject to the monitoring DuBois says he is intent on implementing.

Finally, because Obama has created the OFBNP by executive order (as did Bush), it can be modified–for the worse–by future presidents without approval or oversight by Congress. This is a “major part of the problem,” says Gaddy. “We got the office by executive order; we’re getting a revision by executive order. The next president could by executive order abolish it or say, I want in the faith-based office a panel of advisers that could tell me how to make this nation more religious.”

In the end, progressive religious activists question not only the constitutionality but the entire purpose of the office. “The purpose of government is to serve all the people irrespective of what they believe or, better yet, don’t believe,” says Reverend Monroe. Obama “is pandering to a very conservative base that raised its horrible head during the Bush administration. He can’t find a way to undo that but thinks he can refashion that. But he’s actually just re-inscribing the problem.”