In one last push to mobilize voters, Michelle Obama is asking her husband’s supporters to get viral on Tuesday.

In a final salvo for Super Tuesday, the Obama Campaign blasted an email from Ms. Obama urging supporters to share the new music video "Yes We Can." The video was a smash hit across the web since launching on Friday, bringing direct footage of Obama’s stump speech to millions of people. It already netted over 1.8 million views on YouTube, and potentially hundreds of thousands more from another hub, DipDive.com, which drew over 1,000 links from U.S. websites since last week. The Obama Campaign’s new viral push should bolster those numbers — his State of the Union rebuttal recently topped a million views on YouTube. And Obama’s YouTube profile has drawn over 11.5 million views, more than ten times Hillary Clinton.

While Obama is tapping energized supporters and intrigued viewers to basically spread his message for free, Clinton invested in an hour of national paid media with a televised town hall on Monday night. The "Voices Across America" event was broadcast on the Hallmark channel, and streamed on HillaryClinton.com. (Neither Hallmark nor the campaign would comment on the cost, according to MediaWeek.)

Of course, all campaigns invest heavily in television, and Obama just bought local Super Bowl ads. But this viral video strategy bolsters and deepens his voter outreach. Obama reaches more people this way, and enables them to share his message with their contacts. He speaks to young voters in their preferred medium. He routes around the traditional media filter — and its penchant for reactive conflict — with a proactive message. (It’s hard to show leadership while parrying Brian Williams’ tactical quizzing, as Obama learned Monday; Video below.)

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

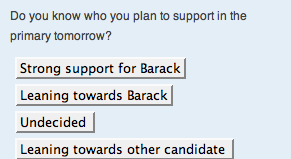

The key is that Obama also asks supporters to do something. It could be forwarding the video for Michelle, or telling their MySpace friends to vote, or busting out a cell phone to mobilize strangers. Lately the campaign has even empowered supporters to call voters from home, punching in their results online:

This week, the campaign’s leading web volunteers made 100 calls per person. The record is 267, held by one Thomas Hargis. National emails about voter contact and polling places are still top priority, an Obama aide told me, and the music video was added for a final punch. Yet this connected activism is not confined to the number of calls made or videos shared. Inviting people to choose their participation in meaningful, interactive ways, from anonymously persuading strangers to shouting opinions across intimate social networks, can tightly bind people to each other and the candidate. That has little to do with Internet technology and, sadly, almost nothing to do with typical campaigns.

"We may finally be coming to understand what De Tocqueville saw – the promise of democratic politics is in people’s ability to enter into relationships with one another to articulate common purposes and act on them," wrote Marshall Ganz, the veteran UFW organizer and RFK backer who advised Obama and Howard Dean on movement-building. "Organizing to bring people back into politics is not a cost, but an investment in rebuilding the democratic infrastructure of our public life under assault for far too many years," he added, in a 2006 blog post.

Unlike Dean, the Obama Campaign does not stress its historic Internet success or run early victory laps in the blogosphere. It does not even discuss the web as an obvious metaphor for Obama’s candidacy: An open frontier where race and gender recede, new ideas vanquish the old, and citizens converse and connect in ways that the prior generations would never understand, let alone support.

Perhaps that is simply because no presidential candidate wants to sound like the next Howard Dean. Or maybe, the campaign knows that you don’t build a movement by talking about it. You do it, person by person, until one day, everyone can see it.