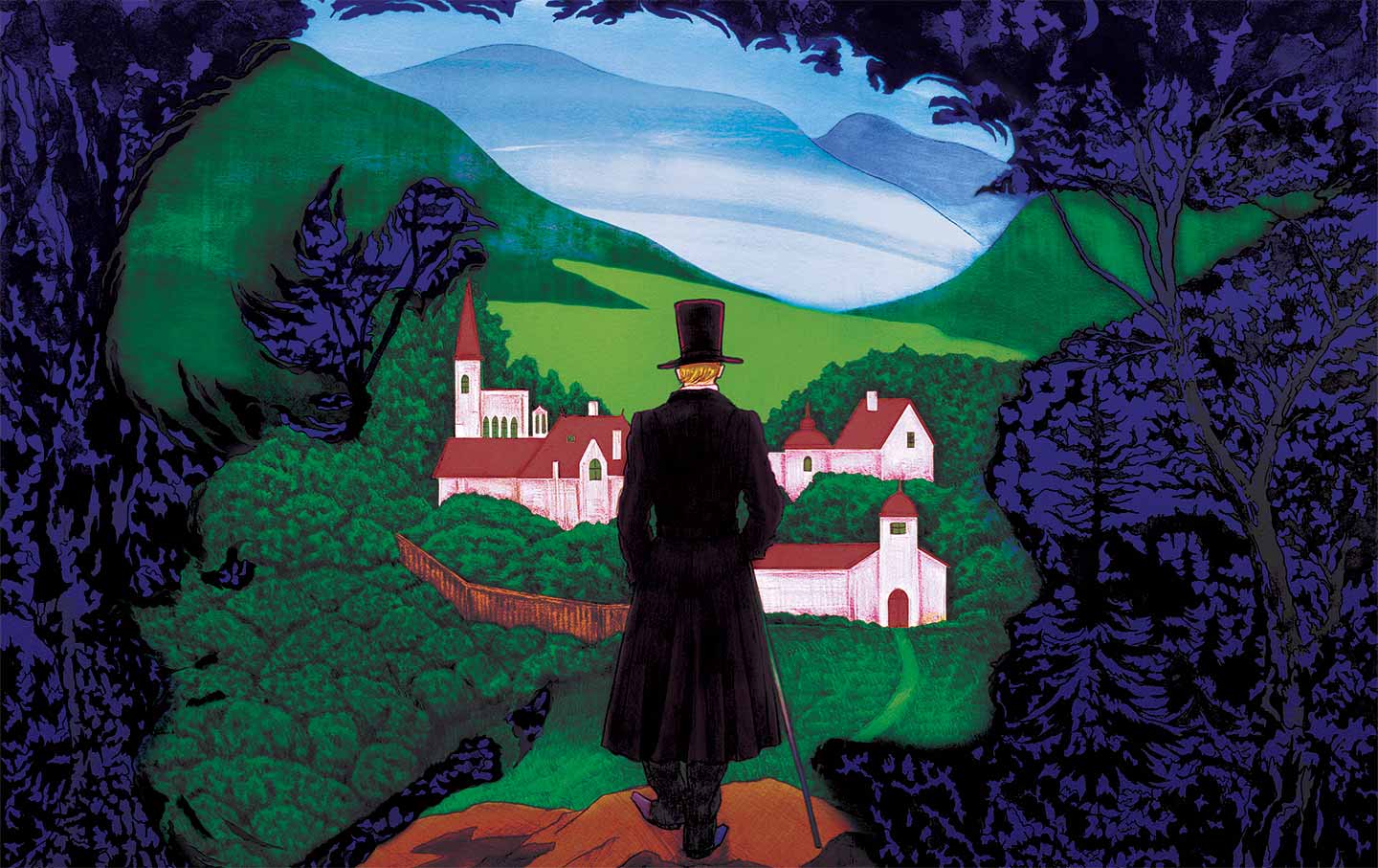

Illustration by Lily Qian.Illustration by Lily Qian.

In his 1956 study The Meaning of Contemporary Realism, the Marxist philosopher and literary critic Georg Lukács distinguished between two literary traditions. Comparing the works of Thomas Mann, whom he considers a realist writer, with the works of Franz Kafka, whom he positions as a modernist, Lukács argued that Mann presents a view of individuals as social and political beings who are firmly rooted in an identifiable time and place. Kafka’s parables, by contrast, for Lukács, are stories of alienated individuals who are meaninglessly “thrown into the world” and they are consequently static and ahistorical.

The Polish novelist Olga Tokarczuk sees the problem of literary form and social change a little differently. In her 2019 Nobel Prize lecture, she speaks of the need to create a new realism, “a sort of neo-surrealism” that goes “against the grain…of cause-and-effect.” For Tokarczuk, the Central European parable is not an alienating literary form but a way of finding a common formula for people’s otherwise disparate lives. “For the hero of the parable,” she writes, “is at once himself, a person living under specific historical and geographical conditions, yet at the same time he also goes well beyond those concrete particulars, becoming a kind of Everywhere Everyman.” The parable, Tokarczuk intimates, has a quality that is not simply anti-realist but also anti-national.

Tokarczuk has long been recognized as one of the most important novelists in Poland since the Cold War. Her novels are comic and melancholy, epically conceived yet resolutely private: They are hermetic puzzles to be solved, novels that quiver with metaphysical ideas that make conventional genres look curiously unfamiliar. Tokarczuk is best known internationally for Flights, her sixth novel, which won the Man Booker Prize in 2018, and The Books of Jacob, which the Nobel committee referred to as her “magnum opus,” a magnificent, deeply researched novel about the 18th-century mystic and sect leader Jacob Frank.

In Poland, Tokarczuk has a reputation for speaking out against the government’s right-wing agenda, and many of her novels align with her political concerns: anti-nationalism, women’s rights, and threats to the environment. One finds these themes in Flights and The Books of Jacob and in her earlier work as well. Her novel Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead, published in English in 2017, was an eccentric, darkly comic feminist murder mystery and a European parable about animal rights.

Tokarczuk’s latest novel, The Empusium: A Health Resort Horror Story, follows in this spirit: It is a feminist noir reworking of Mann’s 1924 novel The Magic Mountain. Translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones, The Empusium is not exactly a literary homage or unequivocal pastiche. It is something more slippery, interesting, and impish: a resonant echo chamber of a transitional historical moment in the collective psyche and the political composition of Europe. In the book, Tokarczuk moves Mann’s story from its setting in the Berghof sanatorium in Davos, Switzerland, to a lesser-known resort, Göbersdorf in the Silesian mountains in what is now western Poland (the treatment of consumption practiced in Davos was modeled after Göbersdorf). But in compressing the time frame of the novel and transplanting its geographical setting eastward, Tokarczuk shifts our interest from Mann’s comic encyclopedia of Enlightenment ideas to the explosions of reality and time that linger on the outskirts of the sanatorium and its grandly deflated narrative of European modernity. In the inert, anachronistic space of the sanatorium, history rushes in.

The Empusium opens in September 1913 with the arrival of Mieczyslaw Wojnicz, a young Polish man, the son of an engineer from Lwów (now Lviv in Western Ukraine) with tuberculosis. His destination is Wilhelm Opitz’s Guesthouse for Gentlemen, one of a complex of health resorts in the Silesian mountains. The Guesthouse stands in the shadow of the Oberdorf sanatorium and is more affordable than the other guesthouses near Oberdorf, but there is a faint promise—narrated with irony from the start—that its occupants will make their way up the health-resort hierarchy.

Mann delights in the fairy-tale temporality of the Berghof, where a new ideal of health creates an intoxicating atmosphere that removes its residents from the concerns of the “flat” world below. But in Tokarczuk’s novel, which was written during the Covid-19 pandemic, the escape from the daily reality of material production entails a confrontation with the specter of the history of reproduction. The Empusium redirects our attention from the beguiling artifice of a triumphant narrative of health to the forests beyond it, where the phantomic presence of femininity—of dead mothers, old witch tales, local fables, and irrational forces—takes hold.

These spectral entities invade the resort as well. Nothing is quite as it seems in the Guesthouse for Gentlemen. Barely a day into his stay, Wojnicz finds the body of a woman (the one who brought him breakfast that morning) laid out on the dining-room table. She is revealed to have hanged herself (or, at least, that is the story presented to him) and to have been Opitz’s wife (who was reportedly treated violently, like a servant).

Opitz and the other residents appear undisturbed by this death and try their best to keep the guesthouse running as usual. But something strange has been released into the atmosphere. As Wojnicz intuits, there is no getting away from the fact that the health resort “was now the site of violent death.” The men continue to debate the place of women in the public sphere, the caliber of their writing, their right to vote, and their inherent irrationality (which makes it seemingly impossible to determine why Klara Opitz killed herself). But these attempts to suppress women and death only drive the power of the unconscious more forcefully into view.

Opitz and his motley crew of bourgeois gentlemen tell each other witch tales they pretend not to believe in, washing down stories of the void with a mystical liqueur, Schwärmerei, and raising a toast—”to hell with Koch’s bacilli” (referring to the scientist who identified tuberculosis)—as they convince themselves that the Balkan conflict is easing up: controlled, rational pronouncements, with chaos trailing behind. On a walk in the forest, Wojnicz, who has been brought up in an enterprising all-male household (with a nanny), is initiated into the culture of the “charcoal burners,” who are seasonal workers in the area. He is also introduced to the totemic dolls or Tuntschi—mossy effigies that evoke the power of something uncanny —that the charcoal burners fabricate to keep themselves company while they labor away in the absence of women.

One of the Opitz guests, a Viennese socialist named Herr August, dismisses a local legend that tells of a collective of women who ran off into the mountains in the 17th century after two of them were condemned to death for witchcraft and who now, as the legend goes, reside in mossy holes in the forest. But he also acknowledges that this story might have hints of something real: He cites a passage from Aristophanes’ The Frogs, of a moment when Xanthias and Dionysus encounter a terrifying and beautiful monster—”the Empusa!”—who keeps changing form, from a bull to a mule to a woman. The empusium represents the underside of the sanatorium: the irrational space that undermines the Enlightenment project of European modernity.

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation

Before she turned to writing fiction, Tokarczuk trained as a clinical psychologist, and Jungian themes run through her work. Her interest in psychoanalysis is manifest in the detective work in the novel—whether of a criminal matter or not—that reveals what is hidden in plain sight. In Tokarczuk’s view, this detective work is often the result of those hidden elements that the men in modern society struggle to see: women in their material, autonomous reality. Much of this unfolds in a puckish way that often approaches slapstick, as when the policeman investigating Klara’s death asks Wojnicz whether he knew her:

Wojnicz wondered what to say.

“Yes, I did, but not all of her.”

“What do you mean?” asked the policeman in alarm.

“I saw bits of her. You see, sir, in that short time she was always on the move, and I saw either a hand holding a tray or a shoe holding the door open.” Wojnicz blinked, as if images of Frau Opitz were passing before his eyes.

As Wojnicz contemplates Klara’s death and the strange totemic dolls of the charcoal burners, he also hears an account of other mysterious deaths from a resident artist named Thilo von Hahn, who is at work on a doctoral thesis on the 16th-century Flemish painter Herri met de Bles. Von Hahn trains Wojnicz to read the landscape around him, as we are encouraged to train our eyes, through her revision of the realist novel, to see something more veritable than apparent reality.

Among the many mysterious elements of the novel is its location. Lower Silesia, now in contemporary Poland and where Tokarczuk lives, has historically been split along the violently shifting seams of Europe’s empires. It has been part of Poland, Bohemia, and the Habsburg Empire. In the 18th century, it was a province of Prussia, and in the century following, it became part of the German Empire. During World War II, Hitler established labor camps in the region, and most of the area’s Jewish population was exterminated. When the Soviet Union redrew Poland’s borders, the majority-German population was removed and replaced with Poles from the eastern territory of Galicia, which is now part of Ukraine.

The implications of these shifting borders in The Empusium are vast, yet also specific. In representing Poland as a mercurial geographic and linguistic terrain, Tokarczuk reveals the nation-state to be a recent historical invention: a fantasy that has proved so compelling in part because the European novel has given the impression that nations are a perennial reality. The Empusium’s idiom drifts away from official German and Polish toward the home of one of Tokarczuk’s greatest influences, the writer Bruno Schulz (killed by the Gestapo on his way home from getting bread in 1942): “Galicia and its singsong, slanty…language, in which the words seemed slightly flattened like old slippers—one could feel safe and at home in it.” This language has been rendered by Lloyd-Jones into English in a translation that is at once evanescent and precise.

Tokarczuk uses language as if it always required translating. She renders borderline states legible and gives form to emergent realities. In this way, her novels might seem like perfect products of world literature, a field that is grounded in notions of readability and universal appeal. But in their translingual arcaneness, they also reveal world literature, as much as world history, to be a fantastical organization of reality, which always unfolds at a remove from the way ordinary people experience the movement of historical events. Skimming the surface of history, the novel is oriented toward the not-yet-historical event that emerges at the point that a common worldview is revealed to be no longer operative.

Get unlimited access: $9.50 for six months.

The Empusium is the first novel that Tokarczuk has published since delivering her Nobel Prize lecture, in which she called—in somewhat utopian terms—for a “fourth-person” narrator who will preserve literature’s “eccentricities, phantasmagoria, provocation, parody and lunacy” and who is also “capable of expressing the vaguest intuition.” We encounter this fourth-person narrator in The Empusium as an all-seeing “we,” a narrative consciousness that goes beyond what might be observed empirically. It is at once an undramatic, witty Greek chorus and a psychoanalyst in an invisibility cloak. “No, we do not regard it as an obsession,” this voice says of Wojnicz’s self-consciousness about his appearance, “at most as innocent oversensitivity. People should get used to the fact that they are being watched.” This is not the voice of paranoia; it is simply one attuned to the collective unconscious.

Tokarczuk’s novels give the impression—much like the historical novels of Hilary Mantel and Penelope Fitzgerald —of a strange, mystical distance between the narrator and the reader, as if reading were not simply an experience of mimesis but of communing with ghosts. The fourth-person narrator taps into the resonances that cross national and historical time and that take her back to a black-and-white photograph of her mother sitting by the radio, waiting for her daughter to arrive in the world. She is attuned to the uncanniness of maternal time. She also seems to have something in common with the three strange women who are glimpsed on occasion in the health resort: “Frau Weber and Frau Brecht” (presumably a reference to the feminist Marianne Weber, author of Marriage, Motherhood, and the Law, and the actress and director Helene Weigel, who is known for her roles in Brecht’s plays, especially Mother Courage and Her Children), as well as a third, unnamed woman who hasn’t been seen in years. The narrator also seems to have some continuity with the otherworldly knowledge of the centuries-old vagrant women who live on in the witch holes and with the all-seeing eye of the forest. At moments, this narrator presses tightly up against the consciousness of our young protagonist, so that he starts to sense something about the world he hasn’t seen in it before:

Suddenly everything dies down, and Wojnicz feels as if it is not Willi Opitz taking their picture, but the entire curved horizon that has become the edge of a gigantic lens…for a split second Mieczyslaw notices…the light of magnesium bounces off the spruce trees and returns to them, briefly coating their bodies in ash…as if this is the overture to an opera, and the spectators in this theatre are the trees.

Ways of seeing in this beguiling narrative landscape are neither partial nor total; the view of reality on offer includes almost everything that is beyond the central character’s own radius. Such a view can be demanding. It can, Tokarczuk implies, also end up being overwhelming.

The Magic Mountain’s narrative rapidly speeds up as it nears its end, as the Balkan conflict encroaches on the stilled time of the sanatorium. In this landscape, Hans Castorp’s Bildung—his coming of age—can only be read as darkly parodic. The sanatorium provides a temporary relief from the constraining reality of bourgeois life. But Mann’s protagonist leaves the inert world of the sanatorium only to enter the deathly battleground of the First World War, from which few of Europe’s young men made it out alive.

Tokarczuk’s novel doesn’t diverge from this violent historical trajectory. But Wojnicz undergoes an unexpected, curious Bildung that allows him to escape the fate of his predecessor. The Empusium ends with Wojnicz, the unlikely moral center of the story, leaving the health resort for a wild, improbable, uncertain future. As he exits with a different name and nationality from the ones with which he arrived, he thinks he glimpses, with the certainty of a ghostly mirage surveyed from a moving carriage, the third invisible woman—but she can’t be sure. The Empusium is easy to follow, yet difficult to fathom; it is cannily constructed and uncompromisingly surreal. By jauntily cleaving to Mann’s text while also inverting it, Tokarczuk has created a narrative in which the parable sits like a temperamental bolt of electricity in the historical orbit of the European novel.

Jess CottonJess Cotton is a writer based in London and a research fellow in English at the University of Cambridge.