The election of Donald Trump has led to a national debate among Democrats about their path to victory. For some, the loss signaled that the party “had moved too far to the left,” embracing identity politics and alienating the white working class. Others, however, noted the decline in black turnout and the need to cultivate the next generation of Latinos, Asians, and progressive whites.

These tensions have played out dramatically in the race for governor of Virginia, where the Republican candidate, Ed Gillespie, has tried to paint the Democratic candidate, Ralph Northam, as an ally of MS-13. Northam went as far as to condemn nonexistent sanctuary cities after decrying Gillespie’s rhetoric as “fear mongering.”

Was this a wise move by Northam? Historical analysis and some research I performed suggests it wasn’t. The two parties have sorted along the lines of race, making appeals to the center of less political benefit to Democrats, because they wind up gaining few votes, while alienating their base.

The Republican Party Did Not Have To Become A Racist Party

In the early years of realignment after Barry Goldwater’s overwhelming loss, some prominent Republicans argued that the Republican Party should court black voters, and many actually put the model into practice, with varying results. In 1966 and again in 1968, Winthrop Rockefeller was elected governor of Arkansas with 81 percent of the black vote in his first election and 88 percent in his reelection. In Mississippi, of all places, Republican Gil Carmichael put up a formidable challenge to arch-segregationist Jim Eastland. Carmichael ran a pro-business campaign centered around the idea that white supremacy was bad for business because segregation had made Mississippi “a third-world country.” He lost with 39 percent of the vote, and lost another gubernatorial election in 1975 with 45 percent of the vote. When another Republican lost to Eastland in 1966, one AFL-CIO chief noted that “You just don’t out-segregate Jim Eastland.”

Eventually Republicans decided to follow the path that one party official outlined in 1963, which was detailed in a book by Robert Novak. “‘Remember,’ one astute party worker said quietly over the breakfast table at Denver one morning, ‘this isn’t South Africa. The white man outnumbers the Negro 9 to 1 in this country.’”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Over the past 30 years, the parties have diverged, driven by elite strategies: with Democrats tying racial liberalism to economic liberalism and conservatives using racist appeals to undermine support for the welfare state. This process has taken time, because most Americans don’t pay close attention to politics, and because political attitudes are set early in life and remain sticky. The Republican Party is full of people who subscribe to racist views, while Democrats are increasingly liberal on issues of race. The result of this realignment is that Republicans are less concerned about alienating their base with racial ads. Summarizing their recent research showing that explicitly racist appeals are no longer enough to change respondents’ views on policies, political scientists Nicholas Valentino, Fabian Neuner, and Matthew Vandenbroek conclude that “Many of our subjects simply did not reject political arguments that explicitly derogate Black Americans.” It’s clear that Republican politicians have internalized this lesson. In New Jersey, Kim Guadagno is running Willie Horton–style ads in a race she’s almost certain to lose. In Virginia, white male House of Delegate candidates are sending out racist mailers attacking Latina candidates over non-existent sanctuary cities. And elected Republicans like Steve King openly flirt with white-supremacist rhetoric. It’s hard to claim, as some political scientists once did, that candidates would face electoral penalties for explicit racism. And it’s about to get much worse.

Democrats Have Moved Left On Race

At the same time, an equally significant, though less commonly discussed, phenomenon is the increasingly liberal views of white Democrats. While many commentators have noted the way that Republicans have leaned into racist appeals, the way the Democratic Party has slowly abandoned such tactics have garnered less discussion.

During the 1990s and early 2000s, many Democratic candidates (including, of course, Bill Clinton) sought to move to the center on race to win over whites. In 2006, David Lubell of the Tennessee Immigrant and Refugee Rights Coalition worried about “Democrats trying to out-right the right” on the issue of immigration. Jim Webb narrowly won a Senate election in Virginia while claiming that the “activist Left and cultural Marxists” wanted to “collectivize” America and calling affirmative action “state-sponsored racism.” When asked if he had ever said the N-word, he responded, “I don’t think that there’s anyone who grew up around the South that hasn’t had the word pass through their lips at one time or another in their life.” That year, nearly a dozen Senate Democrats voted to make English the official language of the United States. This change can also be seen in the way Northam’s political positions have evolved from 2007, when, attacking his opponent for supporting increased penalties for driving offenses, he used the slur “illegal immigrants.”

The party’s slow move left has been reflected in opinion data on Democratic voters. In 1994, the first year that General Social Survey (GSS), a leading national public opinion survey, asked respondents whether they agreed that “Irish, Italians, Jewish and many other minorities overcame prejudice and worked their way up. Blacks should do the same without special favors,” only 15 percent of white Democrats disagreed. In 2016, 35 percent did. (The share of white Republicans disagreeing remained stable at just below 10 percent.) In 1975, when GSS first included a question about whether the government should help black people, 55 percent of white Democrats said black people should help themselves. In 2016, 30 percent did. And in the 1973 survey, when GSS asked whether the government is spending enough to improve the condition of black people, 36 percent of white democrats said it spends too little and 21 percent said it spends too much. In 2016, 62 percent of white democrats said “too little” and just 6 percent said “too much.”

This is not to say that white Democrats are all ready to join the antifa movement. However, the myriad pundits who believe Democratic electoral success hinges on tacking to the center on issues like immigration, while ignoring large social movements like Black Lives Matter, are incorrect. Unlike in the past, white Democrats are racially liberal, so a move to the center could alienate them, with little upside. We can see this reality studying the last presidential cycle, where Jim Webb was broadly rejected by the party. In Alabama, Democrats are running a candidate who openly condemns white supremacy and touts his prosecution of the KKK. Candidates, even far-left ones, are increasingly held to account for their rhetoric on the campaign trail.

How I Studied Racism

To put some data behind these broad trends, I used the GSS cumulative file, which spans from 1972 to 2016 and specifically focused on a series questions that have been asked on most surveys from 1977 to 2016. Respondents are asked:

On the average, African Americans have worse jobs, income, and housing than white people. Do you think these differences are:

A. Mainly due to discrimination?

B. Because most African Americans have less inborn ability to learn?

C. Because most African Americans don’t have the chance for education that it takes to rise out of poverty?

D. Because most African Americans just don’t have the motivation or willpower to pull themselves up out of poverty?

Respondents could choose multiple answers. I study A, C, and D. One positive development is that B (“inborn ability”) was chosen by 26 percent of respondents in 1977, but only 8 percent in 2016. For each of the three answers, I modeled the probability that a respondent would agree that discrimination held back black Americans across party identification for each year, controlling for age, gender, region, and education among whites. A flat line suggests that partisan identification isn’t associated with views on the question, while a leftward sloped line suggests that Republicans would be more likely to agree, and a rightward sloping line suggests Democrats would be more likely to agree.

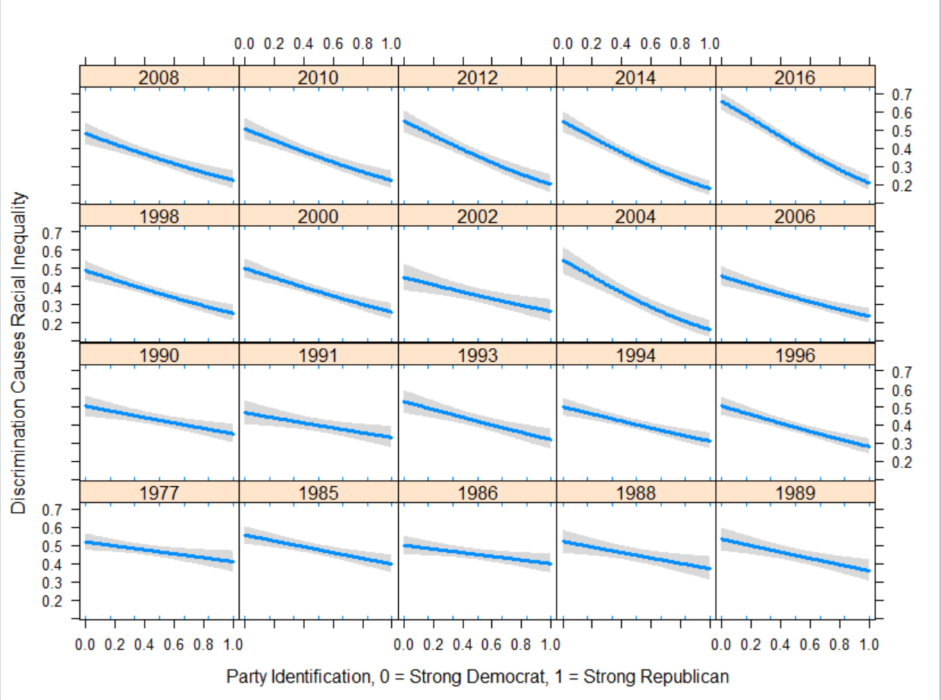

The chart below shows the result of my model for the first answer (“discrimination”). In 1977, the relationship between party and views on discrimination was quite weak (moving from most Democratic to most Republican increased the predicted probability of support by 10 percentage points). By 2016, it was incredibly strong, as evidenced by the strongly rightward sloping line (here, moving from most Democratic to most Republican increased the predicted probability of support by 43 percentage points). To put the data another way in 1977, 44 percent of white Democrats, 45 percent of independents, and 36 percent of Republicans believed discrimination held black people back (an eight-point gap). In 2016, 54 percent of white Democrats did, compared with 34 percent of opponents and 22 percent of Republicans (a 32-point gap).

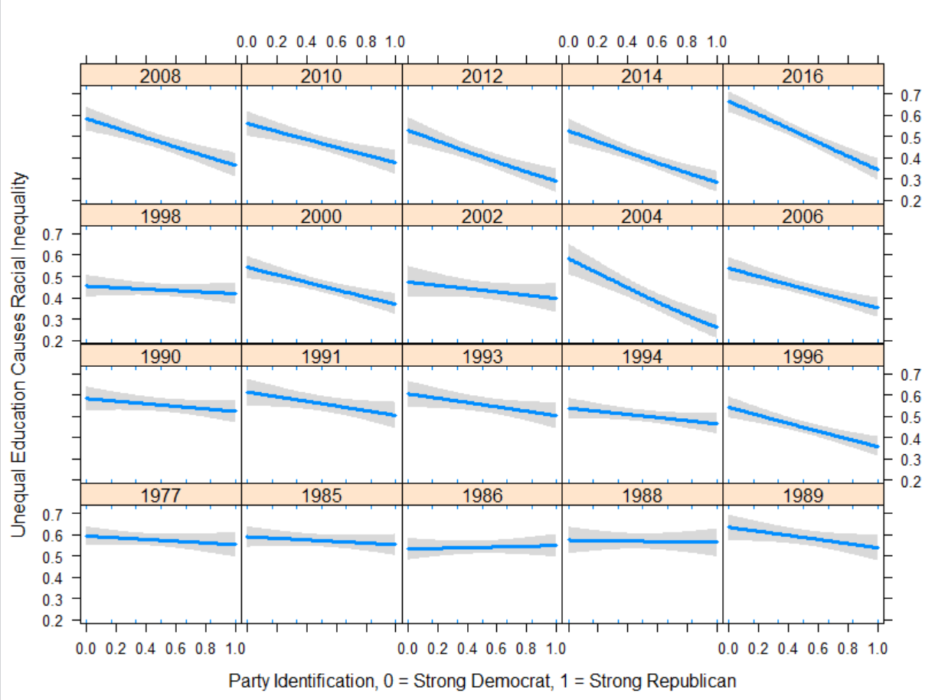

What about education? Here, the visualization again tells the story, but we can also see it in some descriptive statistics. In 1977, 52 percent of Democrats, 56 percent of independents and 49 percent of Republicans believed that black people were held back by the education system (a two-point gap). In 2016, 64 percent of Democrats did, compared with 41 percent of Independents and 39 percent of Republicans (a 25-point gap). In 1977, the party variable did not reach traditional levels of statistical significance in predicting the idea the education contributed to racial inequality. By 2016, moving from the strongest Democrat to the strongest Republican doubled the predicted chance a respondent would agree that lack of educational opportunity contributed to racial inequality.

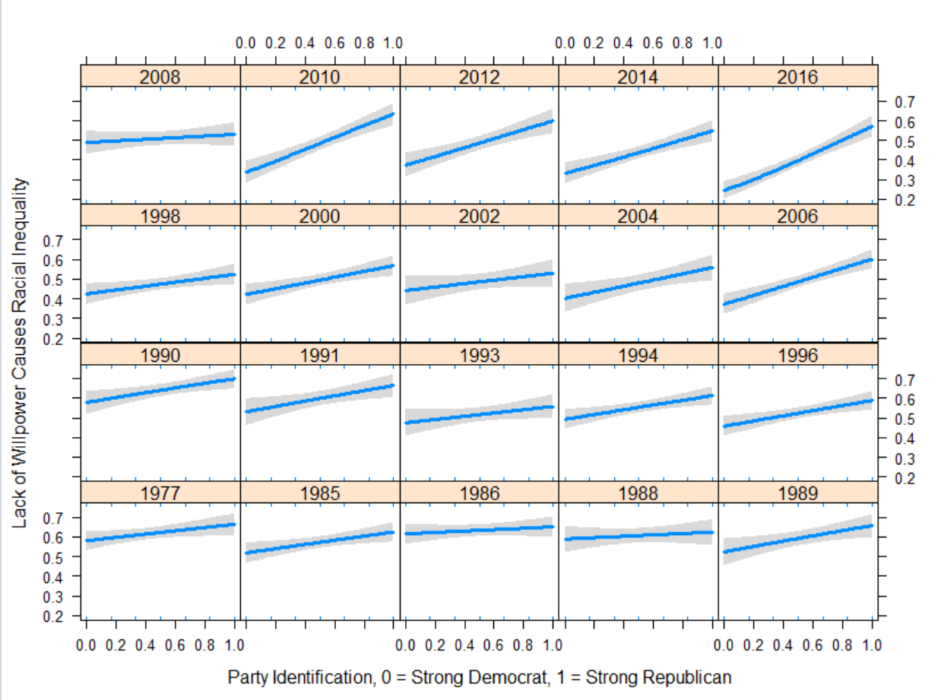

And what about the last question, which blames black people for inequality? In 1977, 63 percent of white Democrats, 66 percent of white independents, and 69 percent of white Republicans blamed lack of will for racial inequality (a six-point gap). In 2016, 28 percent of Democrats, 48 percent of independents, and 52 percent of Republicans did (a 24-point gap). In 1977, partisan identification did not meet traditional levels of statistical significance; by 2016, moving from the most Democratic to the most Republican increased the predicted probability of attributing racial inequality to lack of willpower by 32 percentage points. This points to the key trend outlined above: the increasing racial liberalism of white Democrats, who are far, far less likely to blame black people for their own plight, and far more likely to accept structural narratives about persistent race divides, such as discrimination and unequal access to education.

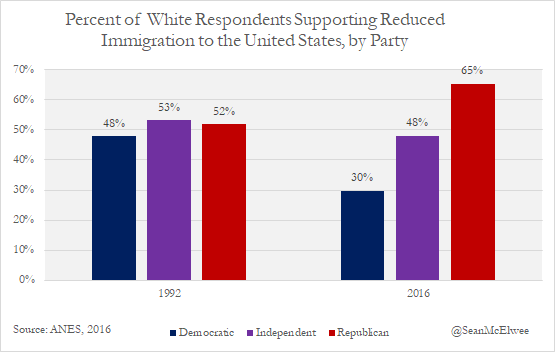

Much like on other racial issues, white Americans have polarized along the lines of party on immigration. As the chart below shows, in 1992, there were virtually no differences across the parties in support for lower immigration to the United States among whites. In 2016, there were deep partisan divides, with 65 percent of white Republicans and only 30 percent of white Democrats supporting decreased immigration to the United States. When candidates tack to the center, they have far more to lose with their own base.

David Baake, a Democrat running in New Mexico’s Second District (which is nearly 50 percent Latino, though the voting electorate leans whiter), tells me that in his race he sees little benefit in adopting a hard-line approach: “Views are so polarized that there isn’t anything to be gained by moving to the right. Such a move would only depress the base, which uniformly favors a compassionate approach to fixing our immigration system.” He advocates for a statute of limitations on deportation, explaining that “Trump’s base isn’t interested in compromise.”

In the late 1970s and early ’80s, there were very little partisan differences in white views about the causes of racial inequality. By 2016, these partisan divides were strong, on a variety of questions. Importantly, much of this result is the dramatic increase in racially liberal views among white Democrats. Despite this, many pundits continue to demand that the party move to the center (or even the right) and abet racism.

My analysis suggests that there would be little to be gained—it’s not the 1980s anymore. Democrats trying to tack to the center or right on race will end up alienating not only people of color in their base but also whites, who hold increasingly racially liberal views. And unlike in the past, there aren’t a lot of voters who are up for grabs, who swing between the two parties. Rather, Republicans have moved right, along with their voters. Much like the GOP couldn’t “out-segregate” Eastland, Democrats won’t be able “out-MS-13” Republicans, and they shouldn’t bother trying. Instead of investing in the squishy (and mythological center), Democrats should invest in turning out their base. It’s still early, but there’s evidence that Gillespie’s racist campaign has bolstered Latino turnout. The future of Democratic party is building a coalition to defeat racism at the ballot box, not pander to it.