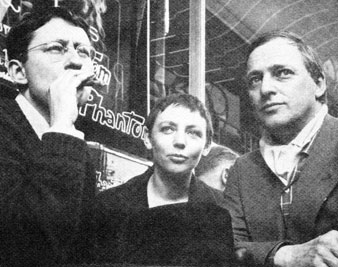

Librairie Arthème FayardGuy Debord, Michèle Bernstein and Asger Jorn, 1961

Librairie Arthème FayardGuy Debord, Michèle Bernstein and Asger Jorn, 1961

Guy Debord’s best lines were ghostwritten.

They are most known from the pamphlet The Return of the Durutti Column, which along with The Poverty of Student Life catalyzed an uprising at the University of Strasbourg that would shortly unfold into the student occupations and general strike collectively known as 1968. Distributed free in 1966, the pamphlet was manifesto, oratory, comic. Its text was largely provided by the Situationist International and its leader, Guy Debord, the postwar period’s most trenchant and implacable political philosopher (and surely the one whose thoughts have been the most caricatured).

One particular frame, a blank back and forth between Pancho and Cisco–“The Situationist Cowboys,” as they would be known–has had a long and varied afterlife, leaping from student revolt to photocopied talisman to album art and T-shirt image for Manchester’s Factory Records; of late it has shown up on the Poetry Foundation’s website, making some point or another.

“What do you work on?” asks the first cowboy, in a white hat. “Reification,” comes the answer. “I see,” says white hat. “It’s serious work, with big books and lots of papers on a big table.”

“Nope,” avers black hat, whom we understand to be speaking in the place of Debord. “I drift. Mostly I drift.” The phrase itself is a ghost. It captures the insouciance that in our era can no longer be attached to radical politics, to the ruthless critique of what exists. And exactly because such a combination, so urgently wished for, can no longer be imagined without this phrase, it is doomed to circulate without relief, like Dante’s Paolo and Francesca borne about endlessly on an awful wind that is the wind of history. Also, it’s a great pickup line.

That’s how it started near the beginning of All the King’s Horses, Michèle Bernstein’s 1960 roman à clef capturing the early hours of the Situationist International. In one version of Situationist myth, Debord talked Bernstein into writing a commercial novel, a knockoff of Françoise Sagan’s madly successful midcentury chick lit. That suggests the style. It’s a lark, a scam.

The slight plot can be as easily coordinated. It takes Dangerous Liaisons and the 1942 Marcel Carné film The Night Visitors–both of which involve a supernally merciless, sensual couple debauching innocents–and asks their bare bones to dance once more. Gilles, with the help of his lover Geneviève, seduces the dewy Carole, a Patricia Franchini manquée down to “the mussed bangs, the short blond hair, dressed like a model child in a white crewneck and a blue sweater.” It’s during the seduction that the famous exchange takes place between Gilles and Carole. Their affair, and Geneviève’s corresponding liaisons (including with Bertrand the poet and mildly modern Hélène), provide the spare narrative. There is the promised drifting around Paris, a vacation to the provinces and then the fall rentrée, rifted with discreet sex and a few tears; the whole thing is over in 88 pages, with dalliances discarded and Gilles and Geneviève affirming their bond.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

The pair are, of course, shades of Debord and Bernstein, founding members of the SI and for a time married. He famously never worked; she found occasional employment as a writer for hire–of, among other things, horoscopes for horses (practice for her later position as a literary critic). She would write a second novel, The Night, close in plot but far from the primal scene of the SI.

The novel ends with the words “I think we’re late,” but the SI was early: first as an artistic avant-garde whose ideas are still being digested (most especially that of détournement, a repurposing of phrases and images that would characterize postmodernism), and then as a roiling cadre of political theorists who early diagnosed late capitalism’s domination of everyday life. They left no novels but this. Long out of print and sold to Situationist fanatics for astonishing prices in bookshop back rooms, All the King’s Horses was reprinted in France four years ago. Perhaps on the basis of size alone, it was bound to leap the Atlantic only to land in the cargo-pants cult of Semiotext(e) pocket books. That series divides itself between “Foreign Agents” (tilted toward shards of French theory) and “Native Agents” (more along personal-is-political lines). All the King’s Horses, officially part of the latter line, more or less splits the difference. This happenstance points toward much of what is remarkable about the SI: never has such a theoretically sophisticated band been so insistent in its demands for everyday life–not living so as to change the world but changing the world so as to live. Or, as they put matters early on, “the point is not to put poetry in the service of revolution, but to put revolution in the service of poetry.” Life would be a practice of theory; this is the import of “Mainly I drift.” It is a refusal of the life on offer: an absurd stroll, a dérive.

At the same time, few would dispute that the SI was all too conventional in some ways, not least in its group dynamics; this volume is charged beyond its internal pleasures not just because it might provide clues to the genesis of the SI but because it represents the only extensive contribution to the SI library written by a woman.

All of this begins to suggest the historical context in which Bernstein’s book finally appears in English, in the somewhat flatfooted translation of John Kelsey (“I walk. Mainly I walk.”). Because of its cult value, the book is condemned to expectations. What one thinks is likely to depend on what question one asks of the book. Radical tract, sly goof, period piece, anthropology of a movement, feminist apparition?

It is surely not the first; little is to be found of the SI’s ascetic philosophical vitriol. Odile Passot’s afterword has a go at the last possibility, misreading history to do so. Greil Marcus, who helped recover the book for English-speaking audiences in his landmark Lipstick Traces via a considered discussion of plot and style, as well as extensive interviews with the author, stands perplexingly accused along with everyone else for slighting Bernstein’s novel out of gender bias. However, there is a kernel of truth in the umbrage; certainly the Situationist International was not entirely hospitable to women, leaving a blind spot in its radical vision. Debord may have been an equal-opportunity tyrant, but his willingness to let feminine beauty stand for something all but magical, even as he savaged the domination of appearance, is scarcely redeemable for all its familiarity. Bernstein points this out, rapier-quick: “Gilles is always the first one to notice the beautiful soul in a pretty girl.” At the same time, the novel does not hesitate to objectify the poor saps batted about by Geneviève and Gilles: “Carole, being herself a poetic object, loved poetry.”

This has the ring of insight, albeit one that comes from a position of self-certain superiority. In this, Bernstein is as glittering and empyreal as any of her cohort. Geneviève’s temporary consort Bertrand is as easily dispatched: the self-styled poet “takes himself for an enfant terrible, and what’s more, plans to write books that will still create shockwaves after he’s dead and gone. He’s very good looking.” In short, he is the usual romantic youth, easy on the eyes and as shallow as he believes himself deep. The retrospective irony is that it would be the SI–not poets to speak of, but theorists and drunkards and enragés–who would create the shock waves reverberating down the century. This irony is repeated in the description of Carole’s avocation: “What jumped out first in Carole’s painting were its pleasantly stylish derivative qualities, not bold blunders of genius.”

But if the foils, Bertrand and Carole, are so conventionally bohemian, might not one say the same of the story? Its promises of shock–amorous cruelty! lesbian encounters!–are little more than a comedy about mores and literary sensation. Indeed, there is something profoundly and familiarly bourgeois about the whole scenario, wherein a true marriage of souls must divert itself with physical affairs lest the partners consume and then weary of each other. It is a French national story, played out everywhere from François Mitterrand’s funeral (famously and calmly attended by wife and mistress) to the Claire Denis vampire film Trouble Every Day. In this regard, the tale is every bit as old-fashioned as the tunes Carole plays for the couple on her guitar, in a scenic garret. They are “classic songs: girls who are beautiful at fifteen, their boyfriends gone to war. Girls who lose a golden ring by the riverside, lamenting the passing of the seasons, who never give up on love. Girls who go into the woods, girls one misses later, at sea, and the voyage will never end.”

These are volunteered as clichés, as romantic banalities. A lesser novel would surely offer us some competing vision of a more authentic life, the brawling and thrill-laden new. But this is not quite what happens; as we have seen, Geneviève and Gilles in many regards conform to equally empty myths. The new life is not on offer as an alternative. Rather, it is hidden within the old, the foolish–within Bertrand’s desire, Carole’s chansons. And the voyage will never end: this lie is surely the only truth, the promise of an endless adventure not lost to the deep past but hiding in the shallows of the present. It will require absolute demands; it will require oblivion.

This is the sense that haunts the book’s contrived conventionality, poking through only momentarily. “Gilles offered to play another game of chess,” Geneviève narrates at one point. “After he’d won, I told him he should teach Carole. And suddenly they were inventing a new game, completely mad: the value of each piece was subjective and changing, decided by the player with each move.” This game is nothing but the drift itself. Its possibility, of another life that can be played within this one, is the book’s secret.

To communicate this secret, the novel must be boring–must make the context in which such a vision makes sense. Its events are scarcely worth remembering; that’s the point. In this it is far better written than Sagan’s novels, which are stylish and diverting and rather modern in their sensibilities; such books wish only to be contemporary. All the King’s Horses is absolutely modern: boring as the surface of administered life, Paris paused between Old World and New Wave, between manners and style. Within that infinitely flat moment, a secret adventure lurks almost in plain sight. It is visible only as the double of the terrible boredom of modernity, can reveal itself only within old songs and romantic notions, at the bottom of a shot glass. The book is familiar with everything, satisfied with nothing, hollowed out as life: “Vodka goes well with a wintery perspective. Nothing else evokes such presentiments of falling snow except, for some, the communist seizure of the state.” But this presentiment is the end of desire, the moment of possibility. “We are partisans of oblivion,” Bernstein wrote in an essay signed only with her picture, in December of 1958, evoking that same frozen contradiction, the Finland Station of the modern. This book is, in its way, the oblivion itself: what must be passed through, the doorway to which the absolute demand comes calling. “We forget the past, the present which is ours. We do not recognize our contemporaries in those who are satisfied with too little.”